Are grammar schools about to make a comeback?

- Published

Education Secretary Justine Greening faces calls from her own party to allow more grammars to be created

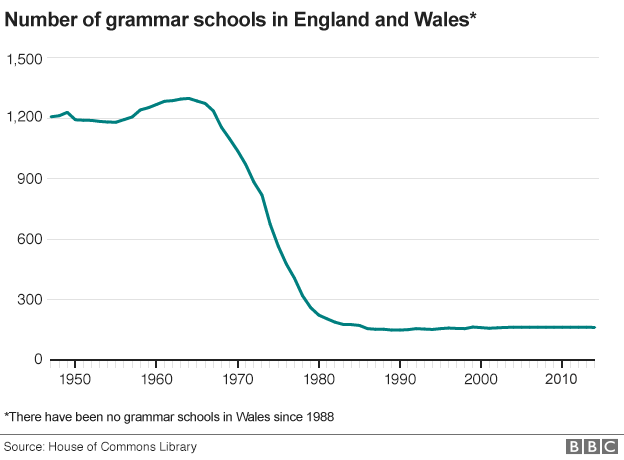

Grammar schools are back on the agenda with a grassroots Conservative group about to launch a campaign for their return.

But if Theresa May's government gave a political green light to such a controversial proposal, how might it happen?

The first step would be the removal of the current ban on opening new grammar schools in England.

This was introduced in the early years of Tony Blair's government in the vain hope of drawing a line under the debate about grammars.

In the Blair compromise deal, the remaining grammars were allowed to continue, unless a ballot of the local community chose to abolish them. But there would be a ban on the creation of any new grammars.

The repeal of this legislation is the first target of grammar campaigners.

But there is also a requirement, created by David Cameron's government, that all new state schools should be free schools, a type of academy set up by community groups or academy chains.

Top of the Form in 1962: Could there be a return to more grammars?

So the most likely route for new grammars would be as a form of free school. These are likely to expand anyway, as there are official forecasts showing an extra 570,000 more secondary places in England are needed within the decade.

But free schools are non-selective and are officially described as "'all-ability' schools, so can't use the academic selection processes of grammar schools, external".

This would have to change to allow entrance tests for new grammar free schools.

But senior Conservative MP and longstanding grammar supporter Graham Brady says repealing the ban on new grammars might also lift the limit on selection by free schools.

A rethinking of free school rules might already be under consideration. The former director of the New Schools Network, Nick Timothy, has called for changes to encourage more faith groups to create free schools.

Mr Timothy is now Mrs May's joint chief of staff in Downing Street and in a key position of influence for any redesign of free schools.

There could also be an imminent opportunity for legislation.

The schools White Paper, launched by former Education Secretary Nicky Morgan earlier this year, was torpedoed by Tory backbenchers over the move to force every school to become an academy.

If there is any salvage from the wreck, it would need to be reassembled into a schools bill in the autumn.

Could that be an opportunity to end the ban on new grammars and change the rules for free schools?

It would certainly be a big symbolic move.

But for the government it might be a big bang for not that many bucks.

Removing a ban isn't the same as announcing a building spree. And a free school approach would depend on groups applying and demonstrating the need for a new school, which would mean years before any bricks were laid.

The level of public demand from parents for a school in which their own children might not get a place remains uncertain.

Alan Bennett's History Boys: Will grammars be seen as helping or hindering social mobility?

Another way of expanding grammar numbers, without building any new schools, would be to allow private schools which were once grammars - such as the old direct grant grammars - to return to the state sector.

For such a move, grammar school campaigners would have to make the argument that academic selection goes hand in hand with social mobility. They will want to be seen as providing a ladder for clever youngsters from poorer backgrounds.

They will present themselves as a lifeline for families unable to afford the house prices that can surround high-achieving schools.

They will be up against much of the educational establishment, as well as the opposition parties, who will argue that academic selection is a direct obstacle to social mobility and that it is really about social selection.

They will warn that the 11-plus entrance exam becomes an arms race of expensive tutoring and grammar schools are likely to have a disproportionately affluent intake.

Graham Brady says the important first step will be the repeal of the ban on new grammars

There have been strong arguments, including from Ofsted chief Sir Michael Wilshaw, that creating a grammar school means a negative impact on neighbouring schools, in effect recreating secondary moderns.

But the tenacious grammar supporters are likely to be feeling more optimistic than for many years.

They will feel Mrs May is instinctively more sympathetic to their arguments. She is part of that demographic whose own school years overlapped with the switch-over from grammar to comprehensive.

And while Mr Cameron's cabinet, with so many prominent former public school pupils, might have been vulnerable to accusations of elitism in education, Mrs May will have much more room to manoeuvre.

Her cabinet has the lowest proportion of privately educated ministers since the 1940s and there are almost as many former grammar pupils as those from private schools.

Grammar campaigners were also heartened by new Education Secretary Justine Greening saying she was keeping an "open mind".

Theresa May is part of the generation who were at school through the change from grammars to comprehensives

This holding position might not be surprising since she had barely turned on the lights in her new office.

But perhaps more revealing were her comments that the school system was no longer a "binary world", with more choice and variety in the types of school.

Could allowing a few more grammars be seen as extending choice? Could they be presented as part of a wider range of options, particularly for the most academically able?

But would this mean the government was ditching Mr Cameron's education reforms. Would promoting grammar schools mean academies were no longer the gold standard? In a school system with such a strong sense of hierarchy, where would grammars fit with promises of "excellence for all"?

The English school system has struggled for decades with whether grammar schools were part of the future or the past.

Grammars are on the faultline between parents wanting both collective fairness and personal advantage. It's that educational anxiety that wants the best for everyone, but something a bit better for yourself.

- Published17 July 2016

- Published15 October 2015