How grammar school changed my life

- Published

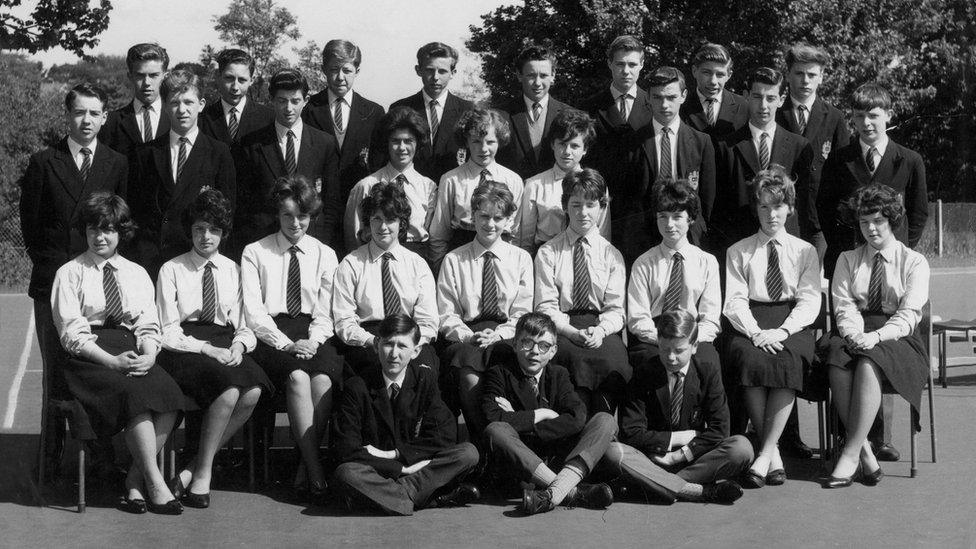

Pupils at Harold Hill in 1963: The grammar school was abolished a decade later

When Norma Jennings talks about grammar schools, she does not talk about statistics or education policy, she talks about her memories of teachers and how her schooldays still make such a strong impression decades later.

The debate about creating new grammar schools in England has heard many attacks on the negative impact of selection.

But to understand the durable appeal of grammars, there's a need to consider a different type of evidence, the personal experiences of former pupils, who can feel that their memories have been shouted down in all the political exchanges.

Norma Jennings has helped to write the history of her old school - Harold Hill Grammar School in Essex - which was abolished as a grammar school in 1973.

And her memories encapsulate how the grammars have retained such a hold on the post-War imagination.

She sent a copy of the book to Prime Minister Theresa May with a letter about what she thought had been lost when most of the grammar system was scrapped.

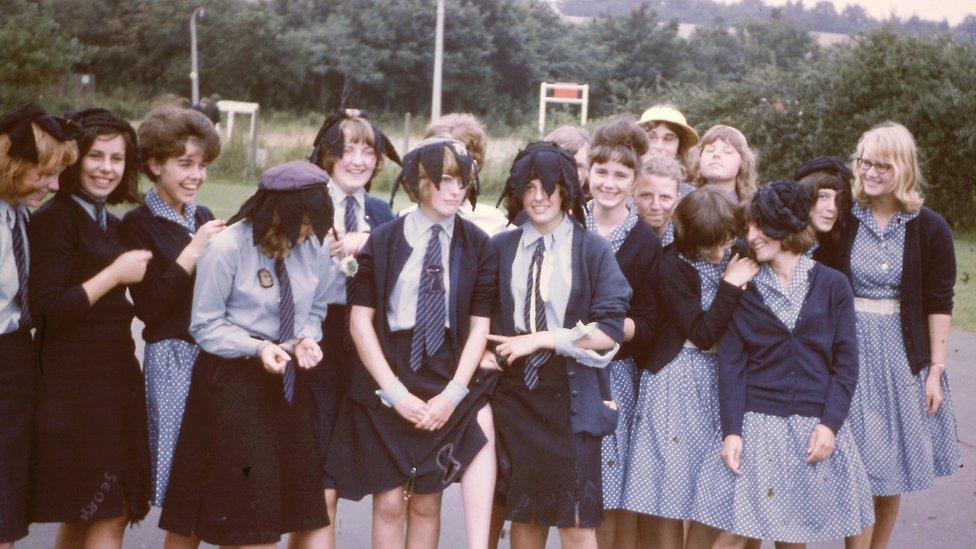

School berets are ceremonially dismantled at the end of the school year in 1964

Harold Hill Grammar School was built in the mid-1950s to serve new overspill estates built in Essex to accommodate thousands of east London families needing homes after the Second World War.

Post-War social planning

It was a piece of deliberate social planning, designed to take the brightest children and create a new generation of professionals.

Mrs Jennings, who left the school in 1963, says it's easy to forget how radical and "revolutionary" all this seemed.

Working-class children were being given the chance to have an education that would never have been within the reach of their parents.

For these children, the first generation of the post-War welfare state, this was a system of free milk and opportunity, and Harold Hill was part of a wave of hundreds of new secondary schools built for an expanding, ambitious population.

Norma Jennings taking part in a school play in the early 1960s

Mrs Jennings's memories also refer to another touchstone of grammar schools - the strong impression made by teachers.

At a recent reunion, she said, there were stories of pupils who had kept in touch with their former teachers all their lives.

'Stamp of curiosity'

For schoolgirls in the 1950s, unlikely to come across many women in professions, female teachers were inspiring role models for staying in education and having a career.

Mrs Jennings talks of the "intellectual life of the school", separate from academic achievement, with teachers setting up all kind of clubs and societies, and leaving pupils with a "stamp of curiosity".

Facing the future with confidence: Pupils at Harold Hill in the early 1960s

It was also a time of assumed values, when the head teacher could unselfconsciously write about staff being able to "distinguish what is first-rate from what is not".

Much of the symbolism and the cut-and-paste Latin might have been borrowed from public schools.

But what made grammar schools so distinctive was that the pupils were not from the playing fields of Eton but the overspill estates of Essex.

And these schools, with a strong sense of their own identity, often left an intense impression on those who spent time there.

Harold Hill was very much a "product of its time", says Mrs Jennings.

And it's hard to know how much the school could be separated from the era.

Boys and girls had separate playgrounds at the school

This was a time of boys being known only by their surnames, teachers wearing gowns, there were hymns and prize-givings, boys and girls were segregated into separate playgrounds and miscreants faced the cane.

It was also a type of education available only to the minority who passed the 11-plus.

End of an era

But as a child Mrs Jennings was not aware of such debates, and she says there was no sense of social separation.

You can only remember the schooldays you had - and not what it meant for those who missed out.

Harold Hill's history also touches on another long shadow over the grammar debate.

How grammar schools were closed has left an often unhappy legacy, with a sense of schools being dismantled without sufficient care for what was being lost.

Theresa May was part of the generation at school when grammars became comprehensives

Mrs Jennings says it would have been better if there had been a way to adapt the selection system, rather than shutting down the grammar schools.

She says the mergers with secondary moderns were often rushed and disruptive, with buildings scattered across different sites.

Mrs Jennings went on to train as a teacher and spent a happy career in comprehensives, but she still describes the way grammars were abolished as a "disaster".

Many former grammar teachers struggled in their new environments.

And there was a whole demographic of pupils at school who faced this upheaval in the 1970s - with a long wake of turbulence, as former grammars readjusted to their new identity.

Disrupted generation

Mrs May is one of the most high profile of this generation, starting at a grammar that became a comprehensive. And who knows how much this has been a shaping experience?

Harold Hill's merger with a secondary modern was not to be long-lasting.

The comprehensive that emerged has also disappeared, and the site has now been redeveloped for housing. Nothing exists of it apart from the memories of former pupils.

Harold Hill was part of a huge wave of post-War school building

Another former pupil of Harold Hill, Colin Sparrow, says his grammar school days were a "melting pot" of different social classes and he had a very positive experience.

But he says if the grammar system had survived, the school would have been "a very different animal" from the one he attended in the 1960s.

In terms of whether they were elitist, he quotes Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee, speaking in 1945: "I am myself in favour of an educational system which will break down class barriers, and will preserve the unity of the nation, but I am also in favour of variety and entirely opposed to the abolition of old traditions and the levelling down of everything to dull uniformity."

Reconciling those ambitions still seems to be as elusive.

Remembering Harold Hill Grammar School by Don Martin and Norma Jennings, Lavenham Press, Suffolk.

- Published15 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016

- Published8 September 2016