Schools must do more on mental health, say School Reporters

- Published

- comments

Grace shares her experience of being bullied

Grace, 16, has been bullied for the past nine years, has moved schools twice, struggled with suicidal thoughts and taken medication for anxiety and depression.

At one point, she says, "there was no-one to turn to in the school and I felt so low I didn't want to go on".

According to research for BBC School Report, half of teenagers with mental wellbeing issues try to cope alone.

And a third said they were not confident enough to speak to a teacher.

At her lowest point, Grace made a "suicide video", which she posted on YouTube.

"I'd get beaten up every week," she says.

"Teachers wouldn't do anything. I even heard the teachers talking about me behind my back."

According to her mother, Sarah, Grace got some help through external music therapy and counselling but little support directly from her first two schools.

Support is better at her third school, where she helps as an anti-bullying ambassador.

She is also a member of the National Anti-Bullying Youthboard, external.

ComRes researchers questioned a representative sample of more than 1,000 UK-based 11- to 16-year-olds, external for BBC School Report:

About 70% had experienced negative feelings in the past year, ranging from feeling upset and unhappy, to feeling anxious, frightened or unsafe

11% described themselves as "unhappy" overall

86% described themselves as "happy" overall

They said the most important thing schools could do to support pupils' mental wellbeing was to provide someone trustworthy to talk to confidentially, but:

18% described the help they were offered at school for their worries and concerns as "poor"

66% described the help they were offered at school for their worries and concerns as "good"

Half said there was an allocated teacher they could talk to about worries or concerns

15% said their schools had appointed older students as mentors

Almost three-quarters (73%) would often or occasionally worry about a particular pupil's wellbeing in their free time.

Over a third had not had any training on how to deal with pupils' mental health issues

A quarter said they would not know how or when to refer a young person in mental distress for help

The most important way schools could help was to provide someone trustworthy to talk to confidentially, said pupils

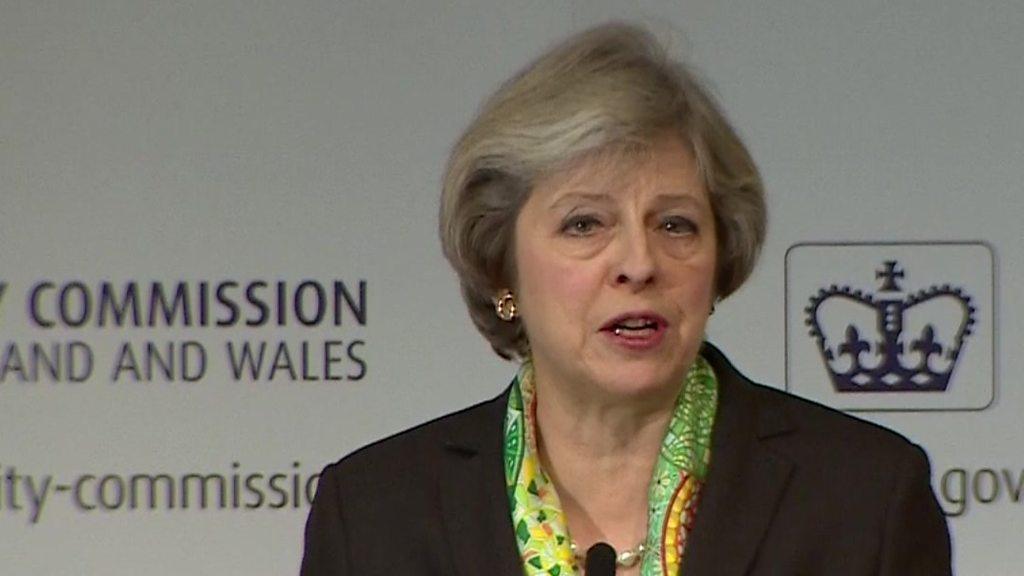

In January, Prime Minister Theresa May announced plans to transform attitudes to mental health, with a focus on children and young people.

The plans include better links between schools and NHS specialist staff and mental health first aid training, external for every secondary school.

Reacting to the School Report research, Edward Timpson, Minister for Vulnerable Children and Families, said the government would "transform mental health services in schools" and was commissioning research to help schools identify which approaches worked best.

"Growing up in today's world can be a challenge for children and young people, so it's vital that they get the help and support they need," said Mr Timpson.

Last year, research for the children's commissioner for England suggested more than a quarter of children referred for mental health support received no treatment.

And on Thursday, commissioner Anne Longfield said the School Report study highlighted "many desperately sad stories" of children with serious conditions being denied support.

She called for urgent action from schools, the NHS and government.

The Family Links and Nurturing Schools Network said schools needed better staff training and enough resources to support and improve pupils' emotional and mental health.

"We must go further to invest in preventative approaches in schools and at home," said the network's chief executive, Nick Haisman-Smith.

- Published1 March 2017

- Published10 January 2017

- Published9 January 2017

- Published20 July 2015