Michael Kiwanuka's career tips strike chord with teens

- Published

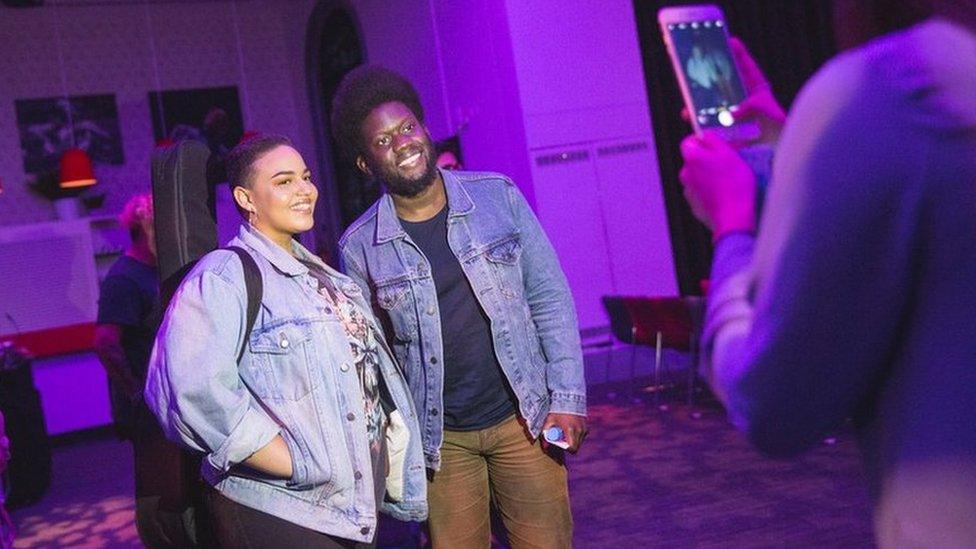

Career tips: Michael Kiwanuka with 17-year-old singer-songwriter Laurie Mann

Singer-songwriter Michael Kiwanuka made his headline debut at London's Royal Albert Hall last week - a few days later he was back, offering career tips to a group of aspiring teenage musicians.

"It was the biggest moment of my life," he told the group, of what has been hailed as a landmark performance, external.

But his mother had had different ideas.

"Don't you get big-headed," she had warned him in a text.

Less than a week later, he returned, to one of the hall's side rooms, to run a masterclass for teenagers keen to follow in his footsteps from the suburbs to stardom.

"I got a guitar and started a band at 12 years old," he told them.

Kiwanuka grew up in north London, steeped in musical culture.

Every spare minute was spent playing music, and he dropped out of two degree courses before he found success.

This admission hit a chord with some of his audience.

Laurie Mann, 17, who performed one of her own songs at the session, herself quit college only last week to focus on recording her own material.

His story "made me feel like less of a loser", said Laurie, who is from Stratford in east London.

"Music is a very creative artistic thing and being educated in how to make music is quite annoying for some people, and it personally was for me."

Pearl Fish, 19, said she had "messed up" her university applications "on purpose" and was now "busking round London", though she planned to go to university eventually.

"It was really wonderful to hear some genuine, down-to-Earth advice from someone," she said of the masterclass.

"It's all about enjoying it and doing it honestly and making music where you can, having goals but just focusing on the music and getting out and just doing it.

"It made me realise that there are other trajectories to go down that aren't just university based."

Pearl Fish, 19, put university on hold to busk round London

But other teenage performers at the event said they were sticking with their education.

Keaton Dekker and Ellie Occleston, both 17, are using music college to boost their performing and recording skills, while gigging in their spare time.

And Myla and Elaria, are both still only 15.

"I am still concentrating on my GCSEs," said Elaria.

"You are amazing," Kiwanuka told the group.

"I don't think I had written a song until I was 20. So you guys are way better than I was at 15, 17, 19."

Elaria, 15, performed wearing her school uniform

At his north London comprehensive in the 2000s, "There were loads of bands, putting on gigs", he said.

"You got handed flyers on the way to school. They charged £2 just to fill up the venue."

And by the time he was 15, the aim had been "to get your band on to the flyer in the 19:00 slot, and then you could stay in the bar until midnight".

In one crowded, rowdy bar he saw Amy Winehouse play before she was famous.

"She silenced the pub with her voice," he said.

One of her band members was ahead of him at the same school.

Three years below him, another singer, Jess Glynne, was beginning her own musical career.

And he met the bass player he still works with at school, aged 16.

But there was a tension.

"My mum wanted me to go to university and get a degree," Kiwanuka said.

He did two A-levels, the minimum he could get away with, and spent all his free time practising guitar.

The compromise was a degree in jazz guitar, at the Royal Academy of Music, which, he said, had gone badly from the outset.

"I couldn't read music and everyone else was classically trained. It was pretty embarrassing every day. I was pretty dejected.

"'That's Mikey,' the teachers said. 'He doesn't know what he's doing.'"

Eventually, he stopped going.

He started teaching guitar, playing in bands, and writing songs in his room, posting demos on social media.

He listened obsessively to bands such as Nirvana to work out how they managed to sound "so simple but so big", while Otis Redding's voice "just killed me".

Some albums, such as Nirvana's In Utero or the Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, he played on repeat, asking himself: "Why does it sound so good, why does it make me laugh or cry?"

"I recorded a song every day, trying to recreate that feeling that you get when you listen to certain songs again and again."

He started another degree, this time in popular music, at Westminster University, but his demos had been spotted online and he was more likely to be found in meetings with record companies than in lectures, and again he dropped out.

"You are amazing," Michael Kiwanuka told the performers

Now aged 30 and with two studio albums to his name, he said: "Thank God I dropped out of jazz guitar."

Emotion in songs was vital, he told the teenagers.

Some of his songs are so revealing that he sometimes takes them off his set lists.

"Some of those things I have never told anyone - but it can be really cathartic.

"One thing I have learned is always break your pattern. Go out of your comfort zone. It makes you think more intuitively and viscerally."

"Be passionate about music," he told them.

"Every you time you want to play, just play, write songs all the time, listen to music all the time, go to gigs all the time, read books, just soak it up, and that passion and love for it will get you through and you won't even think you are working hard."

And on the vexed subject of dropping out: "I think the key is not necessarily to drop out but be true to who you are and if you are somewhere you where it doesn't feel like that and it's costing you your self-worth, then run from that.

"It doesn't necessarily mean uni, just anything like that, if it's a record deal, a band you're in, even relationships, anything like that, just make sure it represents you."