Rookie research: When school science gets 'real'

- Published

Dr James Geach hopes primary pupils could make new discoveries

Modern science produces so much data that scientists can't cope with it all - so why not enlist schoolchildren to help?

The new Sky Explorers club at Wheatfields Junior School in St Albans is making use of a night sky camera which has been installed on the building's roof.

"I am really looking forward to doing all the great stuff we are going to do with the camera," says eight-year-old Cameron. "Looking at space is really exciting."

Throughout the night, the camera takes a long exposure shot of the whole sky once a minute and the resulting thousands of images are made into a time-lapse film for the children to view the next day.

The club members will be on the look-out for shooting stars or meteors and will log where they appear, their direction and the time and send the data to the international All Sky Camera, external network.

Meteors show up as bright streaks of light across the night sky

Dr Jim Geach, a senior lecturer and research fellow at University of Hertfordshire's School of Physics, Astronomy and Mathematics, has shown them what to look for - the long bright lines across the sky produced by meteors as they enter the atmosphere - and how to distinguish them from planes from nearby Luton airport.

Eggs and lemons

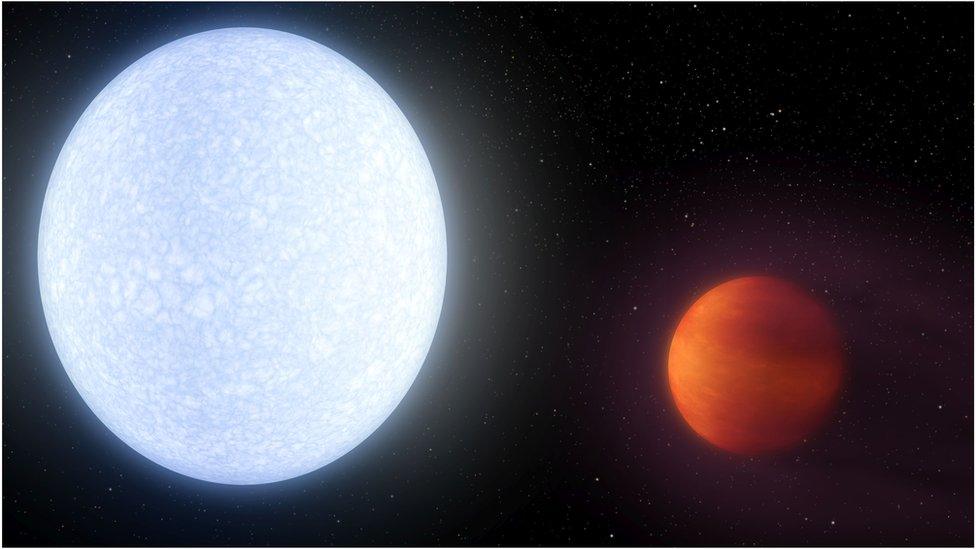

Dr Geach, who studies galaxies, also has a second task for the children, directly related to his own research.

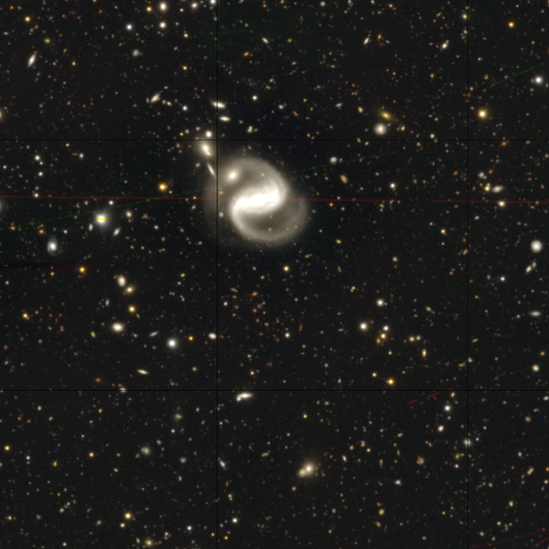

He plans to give the children access to images from the Subaru telescope, external on Hawaii, which takes pictures of deep space, to look for interesting or unusual looking galaxies. "Some of them will not have been seen before and could be very exciting," he says.

He will come to the school every two weeks to run the club, answer the children's questions and evaluate their research.

Some galaxies are lemon-shaped, said Dr Geach

The project has been funded by a grant of almost £3,000 from the Royal Society,, external the UK's science academy.

"If they find anything, scientists will be interested," says Dr Geach.

This kind of engagement by scientists with primary pupils is "one of the things we need to do, as this age is when you can really get them switched on as scientists", he adds.

The Subaru telescope takes images of galaxies in deep space

This view has strong support from Dr Becky Parker, director of the Institute for Research in Schools,, external which runs classroom projects involving scientists from the International Space Station, Nasa and the Large Hadron Collider, among others.

"Students get a diet of quite factual based science in school and yet they have the potential to contribute," she says.

"Why not involve them in doing real science? Teachers find it keeps them inspired and keeps them right at the cutting edge of their subjects.

"Young people don't necessarily just become clever when they get to university. Let them contribute when they are at school."

The Royal Society offers about 20 grants a year to universities and schools wanting to collaborate on research.

"It's all about letting as many schools as possible experience the creative core of science," says Tom McLeish, professor of physics at Durham University and chairman of the society's education committee.

Too often a lack of resources in schools makes encountering real science very difficult.

"But, for example, you would be appalled if students had never put pen to paper when doing art GCSE, or never made any kind of music while doing music A-level.

"If all you have done is learn the facts of what biology or chemistry have shown us, you haven't actually engaged with what it is.

"We are passionately committed to making sure that pupils get as rich an experience of science as we possibly can."

'Exciting and relevant'

Nearing the end of their school careers, sixth formers at The King's Academy in Middlesbrough, external have been chosen to showcase their experiments on the possibility of mimicking the way plants use sunlight to make hydrogen fuel from water at this summer's Royal Society Summer Exhibition, external in London.

They hope their work on artificial photosynthesis, in conjunction with Teesside University,, external could pave the way for a new method of producing hydrogen gas to run cars and fuel cells.

For the last few months the teenagers have spent Saturday mornings and Wednesday afternoons synthesising chemicals at the university laboratories, working with equipment their school could never afford.

Nazmin Akhtar, 17, hopes the project will boost the efficiency of hydrogen fuel cells

Nazmin Akhtar, 17, described how the team developed catalysts able to "split water to produce oxygen and to create the hydrogen gas which is the fuel".

"Obviously we are running out of fossil fuels now, so we need to find new ways of making fuel and sustaining the environment," she says.

"I love learning about renewable fuels - it is one of my passions. I am so glad I chose to do this project."

Her chemistry teacher Brian Casson says the opportunity to work on a project as "exciting and relevant as this" had widened his students' horizons.

"It's been such an eye-opening thing for them... I hope it will turn them into scientists for the future. It really has given them a vision of what science is about."

Teesside University lecturer Dr Anna Reynal, who has been working on artificial photosynthesis for six years, says the students are experiencing real research.

"This has not been done many times and we don't know what the result is going to be. We don't know that it's going to work."

Back at Wheatfields, Dr Geach warns the Sky Explorers that unexpected results can pave the way to new knowledge.

"One of the most important things about science is making mistakes," he says. "There are no wrong answers."

- Published5 June 2017

- Published6 June 2017