Is it fair to kick out pupils halfway through sixth form?

- Published

St Olave's in Orpington is an intensely competitive grammar school, with stellar exam results and a long queue of applicants trying to get through the entrance exams.

But it's now at the centre of a row about whether it is playing fair. And it's highlighted a question relevant to many other state schools.

A group of parents at the school are challenging a decision not to let some pupils progress from lower sixth into the upper sixth, because they are not on target to get good enough A-level results.

This is far from unusual - many schools filter out pupils between lower and upper sixth (or Year 12 and Year 13).

But what makes this different is that the parents are trying to launch a legal challenge.

This is still at an early stage. But the parents' lawyers are claiming that stopping pupils moving from lower to upper sixth is in effect a permanent exclusion.

Is it exclusion?

Pupils can be excluded for bad behaviour or bad attendance, but they can't be excluded for not doing very well in exams.

As such, the parents' lawyers argue that these are unlawful exclusions, and they are calling on the courts to order a reversal.

This argument says that there might be admissions rules when pupils start a school, or join in sixth form, but once they have been admitted, any removal of a pupil constitutes an exclusion, and exclusion rules should apply.

The legal challenge wants to stop schools removing pupils between lower and upper sixth form

The school has so far not commented.

But the legal challenge is against a practice used by many head teachers, with selective and non-selective schools operating a variety of entrance policies for lower sixth and then onwards to upper sixth form.

School requirements

These can be formal thresholds, such as minimum grades in exams. Or they might rely on the professional judgement of teachers to decide whether a pupil is suitable for A-levels.

They might be written down as formal "progression policies".

For example, one successful sixth form tells pupils they will be "at risk of not completing" if they don't meet minimum requirements.

Individual schools have their own processes for deciding entry to upper sixth

There are schools that specifically assert their right to exercise their own "discretion" over such decisions.

Others spell out that "progression from Year 12 to Year 13 is not automatic".

And there are colleges that present entry to upper sixth as a separate application process after successfully navigating lower sixth.

No mention of anyone being excluded, removed or kicked out, but if pupils don't meet the requirements, the message is pretty clear that they're not going to be taking their A-levels there.

And schools are currently making their own decisions about where these thresholds should be placed - whether a bare pass or getting high grades.

Schools have not seen this as an "exclusion", but a form of non-admission or non-progression.

AS-levels until now have provided a clearer halfway point during sixth form.

But their separation from A-levels, and their gradual disappearance, will make it even more a case of schools setting their own internal targets.

League tables

Hovering in the background is the spectre of league tables and the risk of perverse incentives and unintended consequences.

Removing weaker students before they take their A-levels will boost average results for a school.

Helping a struggling student to get a D rather than an E, might make a big difference to that individual - but it's not going to do much for the league table rankings.

There won't be a page on the school website talking about how many students achieved a few hard-fought E grades.

In fact, for high-achieving schools, it might look better if struggling pupils didn't take their A-levels at all, or at least shifted to another school or college.

The reason they might be so high achieving is that they have only high-achieving pupils taking the exams.

But is this the logic of competition between schools?

There is also the question of moral obligation.

If a school has taught pupils since the age of 11, if the school has been the centre of their friendship groups, if it's where they have put down their roots, it seems tough to push them out the door at the very last stage.

If they haven't been very successful in their exams, perhaps the school has some responsibility as well.

There might plenty of parental sympathy for families seeing a pupil pushed out after lower sixth and having to scramble round for another school.

And there are no league tables for the heartache for families.

But from the perspective of schools, any legal involvement in such decisions is going to get very complicated indeed.

Could lawyers get involved in every individual decision about whether someone should move into upper sixth?

And even if pupils were admitted to the upper sixth, could schools be required to enter pupils for A-levels, if the staff thought them unsuited? Or would there have to be a further legal battle over each exam?

An acrimonious exchange over this is suggested in the legal challenge at St Olave's.

The school seems to have said pupils could return but they would have to take a vocational qualification in health and social care rather than A-levels.

The next stage of the legal process will be next month. But the debate has already begun.

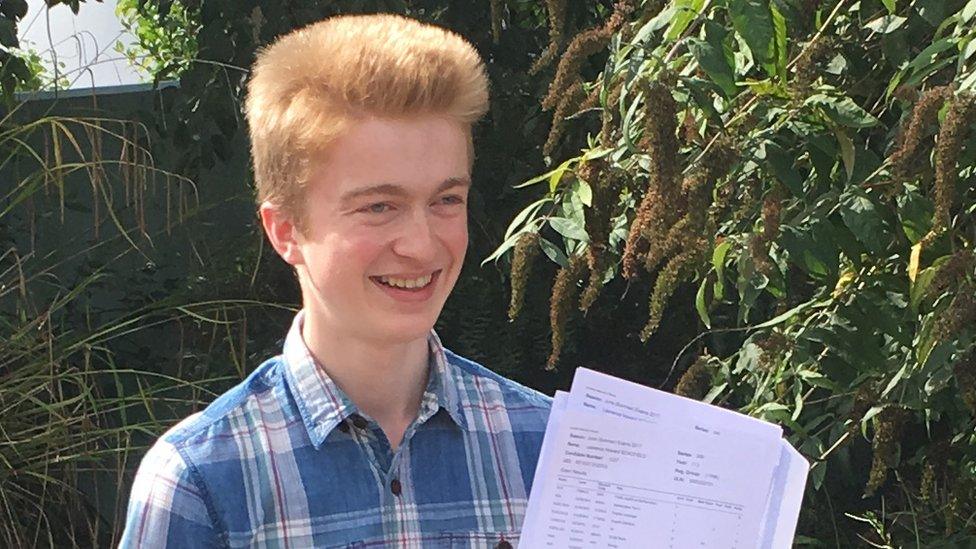

- Published24 August 2017

- Published24 August 2017

- Published24 August 2017