Universities could be accused of 'mis-selling courses'

- Published

- comments

Universities could be accused of "mis-selling" courses to teenagers who have little understanding of money matters, the public spending watchdog says.

National Audit Office head Amyas Morse said young people were taking out large loans to pay for tuition fees without much effective help or advice.

It compared the higher education market to financial products, highlighting how little regulation universities faced.

The government said its reforms were helping students make informed choices.

But the NAO report highlights that tighter rules apply to the sale of complex financial products than to universities offering courses that may well be more expensive.

Mr Morse said: "If this was a regulated financial market, we would be raising the question of mis-selling."

'Minimising risk'

The report says a student loan is likely to be a person's biggest sum for borrowing after a mortgage and will require a long-term commitment.

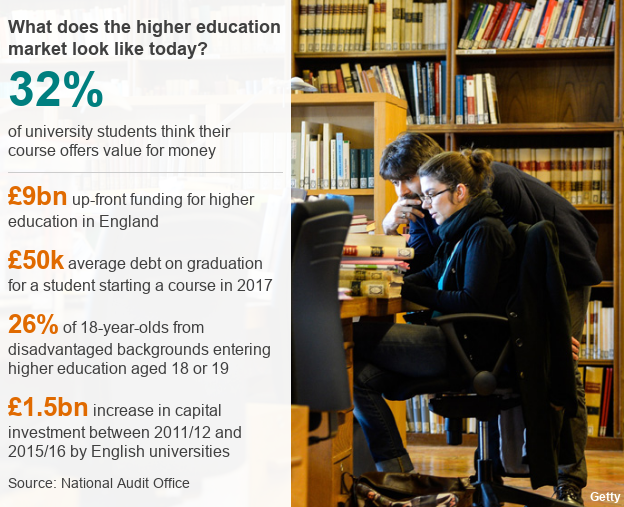

The average loan is expected to top £50,000 by the time it is repaid.

But the decision whether or not to go to university and which course and provider to choose is typically made at the age of 16 or 17.

These choices can have a long-lasting impact on future employment and earnings prospects, the report says.

And where services or markets are especially complex, consumers often need additional support and protection to make good choices.

The report says the Financial Conduct Authority requires companies to disclose clearly the risks of such products to potential customers.

But for universities there are limited comparable disclosure requirements, despite the clear strong financial incentives to attract as many students as possible.

Mr Morse said: "We are deliberately thinking of higher education as a market, and as a market, it has a number of points of failure.

"Young people are taking out substantial loans to pay for courses, without much effective help and advice, and the institutions concerned are under very little competitive pressure to provide best value."

The report also suggests only a third of higher education students say their course offers value for money.

Mr Morse added: "The [education] department is taking action to address some of these issues, but there is a lot that remains to be done."

The report also highlights how despite increased participation by students from disadvantaged groups, they are far more likely to attend courses at "lower ranked providers".

The report does, however, note that students have statutory protections - including the fact repayments are based on earnings and liability is written off after a set amount of time - and that graduates earn on average 42% more than non-graduates.

The government said its student finance system removed the financial barriers for those going to university.

It is also planning a review of tertiary education to ensure a joined up system works for everyone.

'Worth it?'

Meg Hillier MP, who chairs the Public Accounts Committee, said the government was failing to give inexperienced young people the advice and protection they needed when making one of the biggest financial decisions of their lives.

"It has created a generation of students hit by massive debts, many of whom doubt their degree is worth the money paid for it," she said.

But Universities UK said universities had increased investment in teaching and learning, and that students were now reporting record levels of satisfaction with their courses.

"Graduates leaving our universities are also increasingly in demand from employers and continue to benefit from their degrees. They earn on average almost £10,000 a year more than people without degrees and are more likely to be employed."

It added that they would be working with the new Office for Students to ensure that students have the necessary information to make informed decisions and to ensure that competition works in the interests of all students.

- Published7 June 2017

- Published20 July 2017

- Published15 November 2017