Holocaust Memorial Day: A Nazi in the family

- Published

Karl Niemann tending his garden

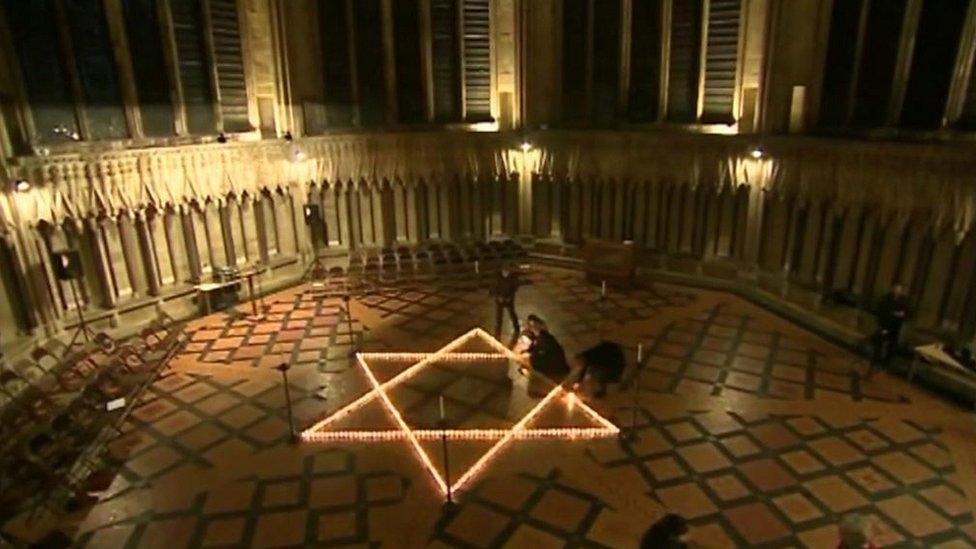

Holocaust Memorial Day is an annual reminder of the six million Jews murdered during World War Two and the millions of people killed in Nazi persecution and subsequent genocides.

This week I accompanied British author Derek Niemann to a meeting in London, where he talked to a Jewish audience about his grandfather, an SS officer in the concentration camps.

It came as the most profound shock to Derek, who writes gentle books about nature, to discover a family secret which had been hidden from him for more than 50 years.

He accompanied his wife Sarah to a conference in Berlin and decided to try to visit the house where his father had grown up during the war, in order to take some photos.

He looked up the address online.

"Up came a sheet which said SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Niemann… crimes against humanity… use of slave labour," recounted Derek.

"I can remember falling back in my chair, going next door, and saying to Sarah - I've just found my grandfather."

Sarah said: "I said, what do you mean you've just found your grandfather? And he explained. I can remember the look of complete and utter shock on his face."

Karl Niemann, Derek's grandfather in Nazi uniform, and grandmother Minna

This was the moment which took Derek's life on a complete turn.

"I'm a nature writer. I write about bees and butterflies. I don't write about Nazis," he said. It was all about to change.

Years of research, delving through archives, visits to Germany and difficult conversations with family members, produced the complex story of an ordinary man, captured vividly in Derek's book A Nazi in the Family.

Derek's grandfather led a double life of family man and organiser of slave labour in the concentration camps.

A pen-pusher, is how Derek's father Rudi described him - but it turned out that he rose to the equivalent rank of an SS captain and organised slave labour in the concentration camps on a colossal scale.

Derek and Sarah were aided in their quest by one of Karl's hobbies - he was a keen photographer. They discovered a treasure trove of about 500 old negatives which had been left in the house in Berlin which he abandoned in haste towards the end of the war.

Incredibly the negatives had been saved by the Jewish family who were given the house in war reparations.

They reveal the intimate minutiae of a loving SS family, and a man who led a contradictory double life. He travelled to all the concentration camps, doing the financial books and running an SS commercial enterprise producing furniture and war supplies - all made by slave labour.

But in the evening he came home, tended the garden and helped raise four children. His oldest son, Dieter, was killed in the closing days of the war, fighting with the Panzer tank division.

Karl taking his oldest son Dieter to join the Panzers in 1944

Skeletal men in striped uniforms even visited his house to do odd jobs. His wife Minna gave them food, although she'd been told not to do so.

Karl's bookwork even seemed to lament the financial challenges of running a business which kept killing its workers and the unfortunate need to order coffins for them.

"He was a bit of a failed mediocrity, my grandfather," said Derek, "He'd been sacked from his job. He felt disappointed in life. And I think the prospect of wearing this glamorous uniform, of being a somebody appealed to him.

"He felt important. He got to the point where a chauffeur would turn up and take him to work. He was obeyed. He was a man of power. I think he liked it."

Derek thinks wearing the Nazi uniform made his grandfather "feel like he was a man of power"

This week, Derek gave a talk about his grandfather to a Jewish audience in north-west London. He was invited there by the Jewish service organisation B'nai B'rith. The BBC has been asked not to reveal the location.

He told his audience, many of whom were descendants of concentration camp victims, about one particularly shocking childhood memory his father recounted, even though he was suffering from dementia.

"He could remember the family staying in the SS barracks [at Dachau concentration camp] and his parents were at the window looking out at a low building with smoke rising from a chimney.

"His mother said to her husband - 'You know what they're doing there?'."

"And his father answered - 'No'."

"His mother said - 'They're burning the Jews. They're killing them, and then burning the bodies'."

"My grandfather then said - 'No, they wouldn't do that'."

"My grandmother said - 'Yes they would. Can't you smell the flesh?'."

Derek's father remembers the family staying near Dachau concentration camp and Karl dismissing what was happening there

During his research, Derek questioned Holocaust historians closely about his grandfather's refusal to admit knowledge of mass murder.

"I said to them - 'is it possible that my grandfather did not know what was going on? Is it possible that he could go to camps and see skeletal figures, see beatings, see people being killed and not know what was going on?'."

"And they said - 'it is impossible'."

Derek was asked by a member of the audience if the denazification process after the end of the war was effective?

Derek told them he didn't think it had any effect at all.

"My grandfather, in common with other SS officers, went through a very intensive brainwashing exercise. If you look at about 300 Nazi criminals who were in Landsberg Prison awaiting the death sentence, not one of them - not one - showed contrition for what they had done.

"They would very happily find religion. They would happily find priests who would absolve them of their sins, but they would not show any contrition whatsoever. They were so brainwashed."

Karl was interned in prison camps for about three years after the end of the war, and was sent to the denazification commission and charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

But he was lucky to be found guilty of being only the lowest grade of offender - that of a Nazi follower - largely because the most incriminating evidence against him had been sent to the War Crimes Trials in Nuremberg to convict his immediate boss, who was executed.

After the war Karl Niemann was charged with war crimes. He was found guilty of the lowest grade of offender, that of a Nazi follower.

The Jewish audience were visibly moved by what they heard.

"I think it is very shocking to hear that none of them showed contrition," said one woman.

"It was like a mirror," said a man, "He was describing one side of the mirror - the German side. And I was looking at it from the other side, because my grandfather was in Dachau."

"The banality of evil is an expression we've all heard before," another man said, "But it is an exact example of that, isn't it? An ordinary man, doing extraordinary things - extraordinarily wicked things."

Another audience member, Noemie Lopian, translated a book her father wrote called The Long Night about his four years in concentration camps.

"At the end of the day we are all, in inverted commas, ordinary human beings," she said, "And we all have a choice. We all have the ability to do evil."

Hear Andrew Bomford's full report on Radio 4's Broadcasting House programme on Sunday 28 January at 09:00 GMT and then on iPlayer afterwards.

- Published26 January 2018

- Published25 January 2018

- Published4 January 2018