Solidarity and determination on the PhD picket line

- Published

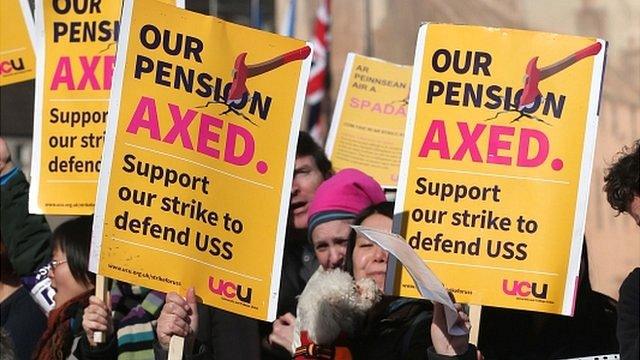

University staff such as Teresa Grant (centre) say morale on picket lines is good

"This was the first time I had ever voted for strike action... I was so furious."

Dr Teresa Grant, associate professor of Renaissance theatre and a former deputy head of Warwick University's English department, says she almost always votes against strike action - but this time it was different.

"If the reforms went through, I would lose £6,500 a year.

"People have worked out you would have to be on strike for 11 years in order to lose the amount you would be losing from your pension.

"So I'm quite prepared to strike for at least five years if that's what it takes. I'll still be quids in."

Dr Jon Rourke, admissions tutor in Warwick's chemistry department, is equally resolved.

"The money aspect isn't a surprise. I think it was clear once we started, you're committed for the long term.

"This is a binary thing. We either get the defined-benefit pension or we don't."

Their main concern is for their students.

"I love teaching. I love my students. I feel very sorry for them. But I have to say not one single student has said to me, 'This is ridiculous.'

"They've all been totally supportive," says Dr Grant.

Senior research fellow Dr Sam Watson delivers just two lectures a year in global health and health economics to students at Warwick Medical School - both fell on strike days.

"I was quite disappointed. I was quite looking forward to delivering them," he says - but, for him, solidarity in the pension dispute came first.

University strikers reject pension deal

Reality check: Are university pensions billions in deficit?

Dr Grant says she has always been financially savvy and has savings to tide her through the strikes.

Her concern is for those struggling to get a foothold on the academic ladder - people such as PhD student Roxanne, who works three zero-hours teaching jobs at the university to maintain herself and fund her studies.

Roxanne says that, initially, the prospect of strikes made her "very nervous".

"I lose 100% of my potential pay."

Roxanne says she barely manages to pay into the pension - but one day she hopes for a permanent academic job and proper pay.

For her, the battle over pensions feeds into concerns about her own future and that of higher education as a whole

"Pensions are of course a massive issue... but it's a symptom of a wider problem in academia where you've got outrageous fees, you've got lack of support for the humanities, you've got these casualised contracts.

"All these things build and build and build and this was the straw that broke the camel's back."

Almost half of universities use zero-hours contracts to deliver teaching, according to the University and College Union, external, with 68% of research staff on fixed-term contracts - though the university employers' association, UCEA, calls the union's research flawed and misleading, saying casual staff do only a very small amount of teaching.

The union says it has gained members during the dispute. And Dr Andrew Marsh, an associate chemistry professor, says a growing understanding of these wider issues has definitely helped build support.

"The more you talk to people, the more they understand what the big issues actually are.

"Yes it's about pensions but, fundamentally, its about defending higher education against further cuts and marketisation.

Of his own generation of academics he says: "We're really fortunate in that we've worked for probably the majority of our careers within a system where we have been well supported and I want to see that continue in the future for future generations and I think that many of the students understand that.

"Several of the students have said to me, 'Do what you've got to do.'"

- Published13 March 2018

- Published13 March 2018

- Published4 March 2018

- Published21 February 2018