Is there a north-south divide in England's schools?

- Published

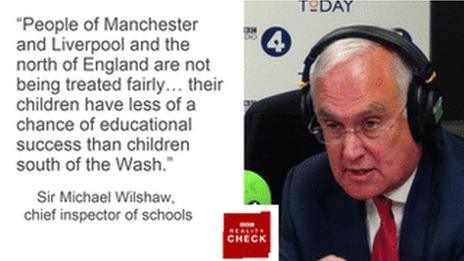

Children in the north of England are finishing school with poorer grades and are less likely to go on to further education. That was the conclusion of a report from the Children's Commissioner,, external Anne Longfield.

It's one in a line of reports pointing to the deep discrepancies that exist between England's schools in all areas of the country.

And it's not always as simple as north vs south.

So what's driving the divide?

There are varying levels of deprivation

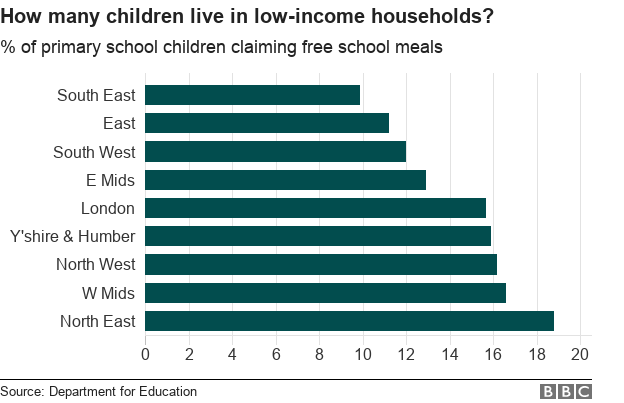

There were higher proportions of children claiming free school meals, external in the north of England and in the West Midlands than in most of the south in January 2017.

Free school meals are often used as a measure of how many children are living with some level of disadvantage.

They are available to children living in households claiming one of a range of income-dependent benefits. Once universal credit - which is replacing six existing welfare payments - is fully rolled out, free school meals will be available to households earning less than £7,400 a year excluding income from benefits.

And many children receiving free school meals in the north of England have been receiving them for longer than children in the south - a measure of long-term, entrenched deprivation.

There are strong links between deprivation and how well children do at school

The link between deprivation and how well children do at school, external has been well-documented.

It's very difficult to pick apart the reasons for this.

In her report on children in the north of the country's experiences of education, Ms Longfield pointed out that more than half of schools in the poorest neighbourhoods in the north of England were rated less than good by Ofsted. This means children face a "double disadvantage of being from a poor community and attending a weak school", she said.

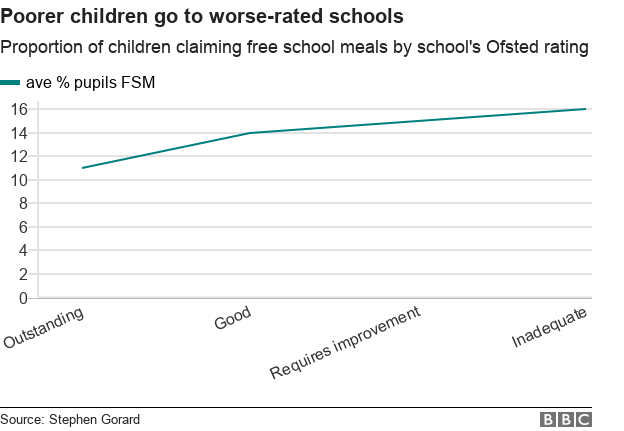

But Durham University professor Stephen Gorard suggests that schools may be given lower ratings precisely because the children they teach are more deprived.

He thinks the strong correlation between how many children are claiming free lunches in a school and how likely it is to be rated less than good is unlikely to be explained by genuine differences in the quality of teaching.

"Inspections are not taking full account of the nature of disadvantage," Prof Gorard says.

They too often mistake raw scores with how well children are being taught, he adds, cautioning that Ofsted inspectors were "overly impressed by schools' level of attainment" rather than looking at children's progress.

But even accounting for that, there are still regional differences when you look at how well schools are rated, external in the comparably deprived areas of the country.

London has the highest proportion of outstanding schools - both overall and in its most deprived areas - and the lowest number of schools rated less than good.

The north-east has the second highest proportion of outstanding schools, but also has the second highest number of schools rated less than good after Yorkshire and the Humber.

It's not as simple as north vs south

In 2015, the government produced figures on multiple indices of deprivation, external looking at seven main things:

Income

Employment

Health deprivation and disability

Education, skills and training

Barriers to housing and services

Crime

Living environment

And this gives you a much more complicated picture - it's not quite as simple as "south=rich, north=poor".

Some of the most and least deprived neighbourhoods can be found all over the country. The figures show that 60% of local authority districts contain at least one of the most deprived neighbourhoods in England.

But there are particular concentrations of deprivation in the north of England, in coastal towns and in major cities including London and Birmingham.

It's important to note that this measure describes the average make-up of an area - not everyone who lives in a more deprived area will be deprived themselves and there are people living in poverty in generally well-off areas.

East Jaywick in Essex came out as the most deprived town in England based on the government's multiple indices of deprivation

Is London a special case?

Many parts of the south have higher proportions of pupils achieving A*- C grades at GCSE in English and maths than many parts of the north.

Those are the grades generally needed to progress to post-16 education.

But when you compare children from similar backgrounds, a more particular divide emerges - not between the north and the south but between London and the rest of the country.

In fact the biggest gaps in attainment between the richest and poorest children were in the southern counties of Cambridgeshire, Buckinghamshire and West Berkshire.

Children receiving free school meals in London do much better than children receiving free school meals in all other regions.

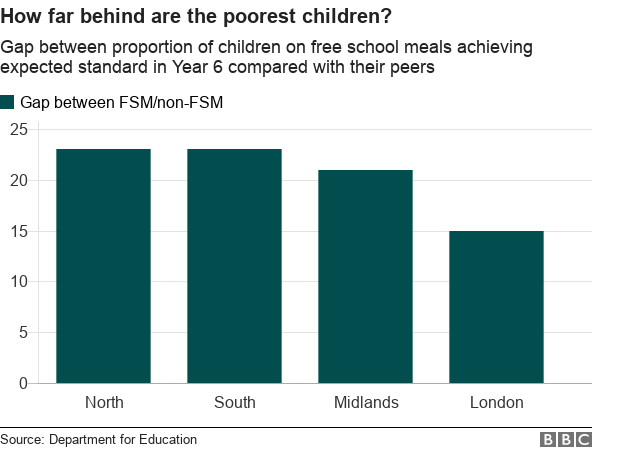

There is a much bigger gap between the achievements of the poorest children and their better-off peers in the north, than there is between children of different backgrounds in London.

This gap exists all through the education system and worsens as children get older.

Children receiving free school meals in London are more likely to reach the expected level of social, verbal and physical development by age four than children receiving free school meals in the rest of the country.

They are also more likely to have achieved the expected standard of reading, writing and maths at the end of primary school (Year 6) and fall less far behind their richer peers than children in the rest of the country.

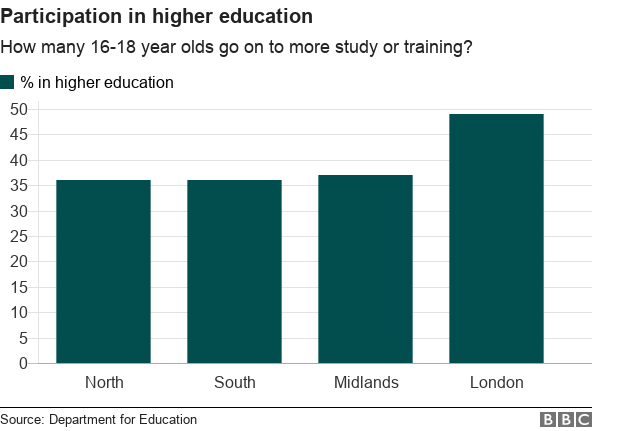

Pupils from all backgrounds in London participate in higher education at higher rates than their peers.

And those who receive free school meals in London are not just more likely than other children from low-income households to go on to higher education - they are more likely to do so than the national average.

But it hasn't always been this way. In 2004, children in London were starting school behind those in the north and behind the national average, but this picture has now reversed.

There's no single reason for this - rather, it is thought to be down to a series of gradual improvements over time, with concentrated efforts by schools and local and central government, starting from the mid-1990s., external

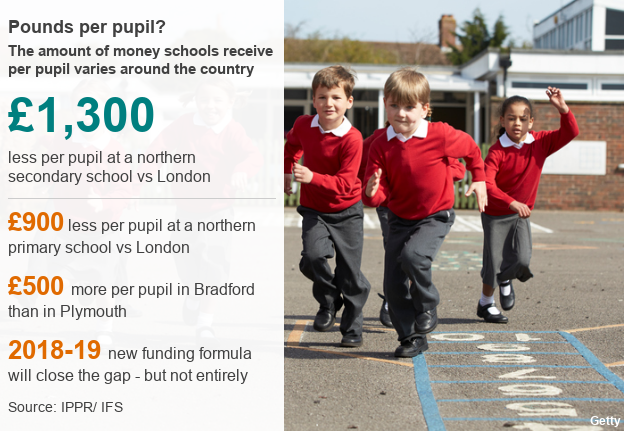

In London, the political focus on improving schools over the past two decades came with significant extra funding - something which has not materialised for northern schools.

The capital's larger immigrant population is also thought to play a role in its better than average attainment.

What about the money?

A new funding formula to determine how much money schools receive is being introduced from next year.

That's the calculation used by government to decide how much money a school should receive.

Every school receives the same basic amount per pupil, but this is topped up by extra funding for things like:

Pupils who receive or have previously received free school meals

Children in the care of the state

Children with special education needs

Children who speak English as an additional language

Schools in areas with a high cost of living

The current formula, which is soon to be replaced, is based on old data which led to discrepancies like schools in Bradford receiving £500 more per pupil than schools in Plymouth despite having similar demographics (because their populations were different in 2004).

Urban areas in the south will receive less funding per pupil on average than those in the north and the Midlands. Rural schools generally receive less money than those in urban areas across the country.

On average, schools in London receive the most funding per pupil. The new formula will close the gap slightly but schools in London will continue to receive more money per head than other regions.

- Published26 March 2018

- Published1 December 2016