Reality Check: Is there a north-south divide in schools?

- Published

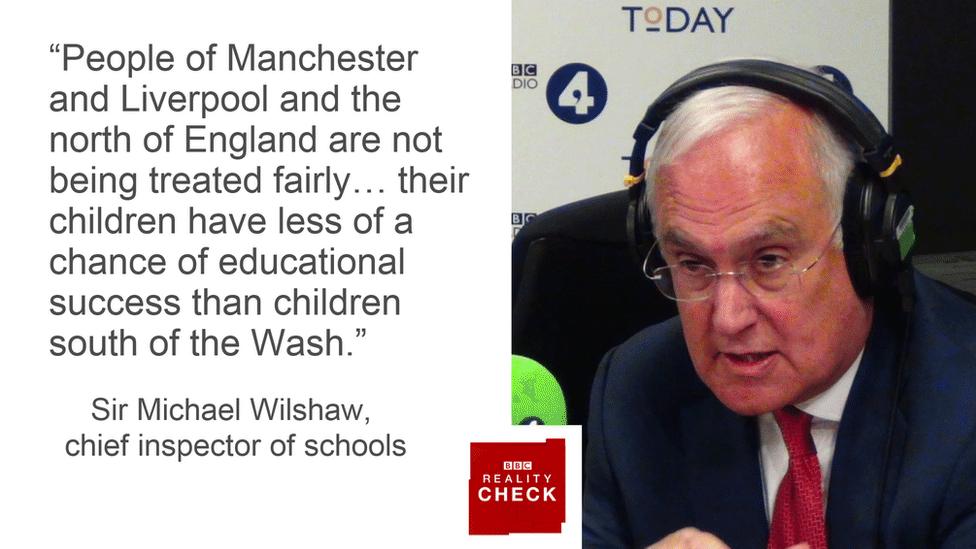

The claim: Sir Michael Wilshaw, England's chief inspector of schools, says there is a noticeable north-south divide when it comes to the rate at which schools are improving, giving children in the North poorer chances of educational success.

Reality Check verdict: There is evidence that the children in the North of England have less chance of educational success than children in the South of England at secondary level, but it is difficult to point to a single reason for this. There is a link between deprivation and poorer school results, but the most deprived areas of London have experienced dramatic improvements in schools in the past 20 years.

The north-south divide in education was a central theme in Ofsted's annual report, external for the second year in a row.

In an interview on BBC Radio 4's Today programme on Thursday, chief inspector of schools Sir Michael Wilshaw said that in northern England "children have less of a chance of educational success than children south of the Wash".

Delivering the report, he said the gap between the North and Midlands and the South was widening and now stood at 12 percentage points - in the North and Midlands, 72% of secondary schools were rated good or outstanding compared with 84% in the South.

This means there are 135,000 more secondary school children being taught in under-performing schools in the northern England and the Midlands than in the South.

According to Ofsted, there are more than twice as many secondary schools judged inadequate in the North and Midlands (98 schools or 6%) compared with 44 in the South and East (3%).

Sir Michael also said that of the 10 worst performing local authority areas, seven were in the North or Midlands and pupils in these regions were less likely to achieve the highest grades at GCSE.

The seven in the North and Midlands were:

Blackpool

Bradford

Doncaster

Knowsley

Liverpool

Northumberland

Stoke-on-Trent

The three in the South were:

Swindon

South Gloucestershire

Isle of Wight

The government says the proportion of good schools is increasing in every region.

It has certainly increased overall - the proportion of schools judged to be good or outstanding has increased by 12 percentage points since 2011.

But improvement is not happening at the same rate across the country, as is clear from the widening gap between the North and the South.

The Ofsted report says that in some parts of the North and Midlands, improvement over the past five years has "stagnated".

"In 2011, the North West was one of the stronger regions, but the proportion of pupils in good and outstanding schools is now just over three percentage points higher than five years ago," it says.

"This means there are only just over 3,000 more pupils in good and outstanding secondary schools in the region compared to an increase of over 90,000 pupils in London in the same period."

Some of this difference will be down to a declining pupil population, but according to Ofsted this does not account for it entirely.

Wide discrepancies

A report from think tank the IPPR, external in 2015 found there was a north-south gap in GCSE attainment, in terms of the number of pupils achieving five or more GCSEs including English and maths.

On average, 55% of pupils in the North and Midlands achieved five good GCSEs, external compared with 59% in the South and East this year.

It's not as simple as just a north-south divide though - there are wide discrepancies in educational achievement across the country.

Coastal communities and more isolated areas of the country, whether in the North or South, have been flagged as areas of concern because of the poor educational achievement of their pupils in the past. And within regions, or even smaller local areas, there can be big differences.

For example, you can look at numbers of pupils getting the English Baccalaureate or EBacc - a performance measure for schools based on how many pupils get good grades in core "traditional" subjects such as English, maths, sciences, history and geography.

In outer London, 32% of pupils achieved the EBacc, compared with 22% in Yorkshire and the Humber.

On a more local level, Leeds had the lowest proportion of young people achieving the EBacc at just 4%, compared with 52%, the highest in the country, in Richmond Park.

But if you look to Bournemouth, you can see that in the Bournemouth West constituency, like in Leeds, 4% of pupils achieved the EBacc, while on the other side of town in Bournemouth East, it was nine times higher at 36%.

Primary schools in the North and the South, however, have similar proportions of good and outstanding schools.

It is hard to say why this gap at secondary level in particular exists.

There is a well-documented link, external between deprivation and doing worse in school.

But London, home to some of the most deprived areas in the country and once also home to some of the worst schools, has experienced a dramatic turnaround in the quality of its schools.

Some have suggested it could be, in part, due to the positive effects of immigration, external, but the general consensus is there is no one single reason.

Rather, a general and collective focus on raising standards from the early years onwards has led to gradual improvements over time, external.

- Published1 December 2016

- Published1 December 2015

- Published12 November 2014