Have youth service cuts led to more crime?

- Published

The claim: The Labour MP published a tweet suggesting rising violent crime could be linked to cuts in young people's services.

Verdict: Youth services have seen big cuts in their budgets over the past few years. However, it's impossible to make a clear link between that and a rise in violent crime.

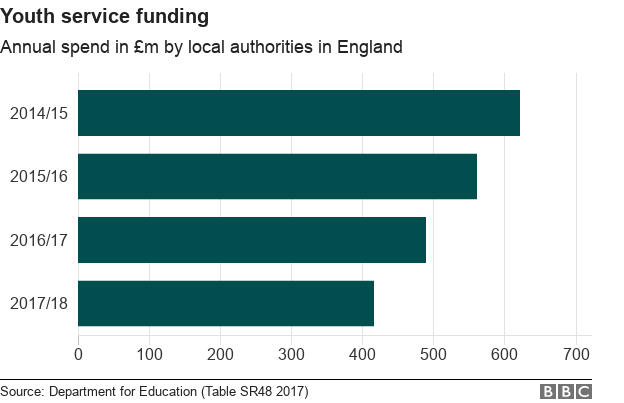

Youth service spending by local authorities in England is down by a third compared with three years ago, according to figures for the Department for Education (DfE).

When we refer to youth services we're talking about youth clubs, after-school clubs but also things like teenage pregnancy advice services.

The DfE data, external shows that over the last 12 months, councils in England were expected to have spent a total of £416m on youth services.

That compares with £489m the previous year.

And if we go back to 2014-15, English councils spent a total of £622m in that year.

That means councils are now spending £206m less this year than they did three years ago.

Another way of looking at it is spend per pupil.

In 2015, councils spent £48 on youth services per pupil (that's worked out after you factor in the money spent by the council, minus any income received).

Today it is closer to £31 per pupil.

So Ms Hayes is certainly right that spending on youth services has been cut.

Funding for individual Sure Start centres has also fallen during the same period - from £648m in 2014-15 to £445m last year.

But it should be pointed out that other areas - such as child protection and looking after vulnerable children - have seen their budgets rise over the same period.

This suggests that councils are prioritising different areas of spending as a result of central government funding cuts.

Is crime rising as youth services are cut?

If we're talking about overall crime and the number of young people entering the criminal justice system, the answer is no.

Despite a cut of one-third in youth service spending, overall youth crime is falling and this is part of the trend that's been observed since the mid-90s.

In the year 2016-17, there were around 75,000 arrests of children and young people, external - and by that we mean anyone aged between 10 and 17 - in England and Wales.

The number of young people arrested has decreased by 79% over the last 10 years and by 14% alone in the last year. And it's a very similar trend when it comes to the number of young people receiving police cautions or custodial sentences.

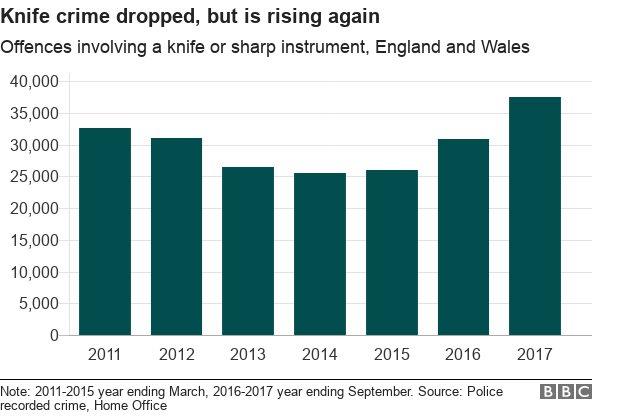

However, when it comes to knife crime, that's a different story. In the same year, 2016-17, children and young people were involved in 4,000 crimes involving knives or offensive weapons - that's an 11% increase from five years ago.

As a proportion of overall knife offences, adults are responsible for the majority of incidents. But last year, one in five perpetrators was under the age of 18 - the highest number for seven years.

And it's that increase in violent crime that's been the subject of recent headlines.

Is there a link between youth services and crime?

So the overall crime figures suggest it's not that simple to draw a link between youth service cuts and offending.

There's plenty of anecdotal evidence out there about the positive impact of youth clubs, but it's proved harder to find reliable research that shows how taking part in these sort of activities can potentially steer someone from a life of crime.

For one, statistics can't tell you how much enjoyment children get from taking part in youth services and how it alters their outlook on life.

On the other hand, an empty room in a youth club with a battered ping pong table in the corner is far less likely to offer a positive experience than a busy club with lots of activities on offer.

Boris Johnson visiting a London youth club in 2013

In fact one study, led by Prof Leon Feinstein and carried out for the Department for Education, external in 2005, found the children who had attended youth clubs with ineffective supervision went on to become more at risk of turning to crime, drink or drugs than those who had never attended a youth club at all.

That research led to the-then children's minster, Margaret Hodge, to declare that "these young people would have been better off at home watching telly than spending their time with others in this way." , external

Other academic literature suggests that organised activities reduce behavioural problems and the chance of criminal activity.

In 2000, for example, Prof Joseph Mahoney, a child psychologist based in the US, tracked the outcomes of 695 youths, external in California and found that those who took part in structured extracurricular activities were less likely to commit criminal offences.

The study showed that the likelihood of committing crime later in life comes down to the quality of services on offer and whether young people have a chance to mix with better-behaved peers, guided by structured activities and respected youth leaders.

But those sort of outcomes are very difficult to measure, especially if you want to produce statistics at a national level - a point that was made in a 2011 Education Select Committee report, external.

Another problem with explicitly linking youth service funding with the recent rise in violent offences is that you cannot isolate other factors that could also be contributing, such as changes to police numbers.

There is no doubt that youth clubs can be a hugely valuable resource to communities. But as to whether they can actually keep crime down - the jury's still out.