The neighbours building hope after losing children to suicide

- Published

Harry Lisle and Rachel Finke were pupils in the same year at the same secondary school. They barely knew each other but their suicides, only weeks apart, led to an outpouring of grief and brought their mothers together.

Harry's story

In the days after Harry died, there was a "maelstrom" of people round the house, his mother, Rose, says.

Teenagers came inside and sat on the sofas weeping.

Rose remembers her 16-year-old son as lively, funny, very clever, very energetic, very popular, with a huge group of a friends and a lovely girlfriend.

"How can you not have known you were that loved?" she asks.

But one Saturday, at the end of October 2016, two weeks after his birthday, Harry tried to kill himself. It emerged he had secretly been buying the tranquiliser Xanax online to self-medicate for social anxiety.

Until that moment, Harry had given away very little about his mental state. Asked if she had had any idea, Rose, a primary school teacher with decades of experience, replies: "Genuinely no - and that makes me feel awful.

"Part of my whole life and job has been about being able to think about other people's emotions."

What the family had known was that Harry, fair-skinned and tall like his mother, was very prone to blushing, and he hated it, to the extent he had asked to be referred to a specialist. But no-one had suspected there was anything more serious.

At the hospital, after his attempted suicide, Rose remembers asking doctors if there was anything to look out for. Would Xanax have effects?'

"He was decided to be low risk so we took him home," she says.

But Rose still wonders whether Harry's decision to take his own life could have been linked to the tranquiliser.

Xanax

Normally available in the UK only on private prescription

Meant for short-term treatment only

Uncontrolled use has been linked to addiction, impulsive behaviour and, in some cases, suicidal thoughts

Supplies bought online are likely to be counterfeit

The family spent most of the following night in and out of Harry's room, checking he was all right. Early the next morning, Rose heard him moving around and went in.

"He said, 'I think I'm probably going to go and play football with the boys tomorrow,'" she says. "I said, 'OK - but let's see how you're feeling'."

It was 4am or 5am, she says, and exhausted, she fell asleep.

When Rose went to wake him for breakfast, she found he had made a second attempt.

They called an ambulance, attempted resuscitation and, "from then on there was just a mad panic of police and ambulance and, yeah, really, really awful".

"As soon as I felt his cold hand," Rose says, "I was just thinking, 'You can't go back.'"

On the Monday, the hospital psychologist rang for Harry, as did the assistant for the doctor he had been seeing about his blushing.

"He did write us a note from the first attempt which was very clear about him not being able to cope anymore and he wanted out... that he loved us all, that we had been great parents, that the Xanax had become a bit of a problem," Rose says.

They had spoken in the hospital about his dependence, how he would cope and the fact "you can't self-medicate".

"Anyway, he decided at that point... what he was going to do. 'Suicide' was on the death certificate."

Rose describes the difficulty of thinking she knew her son really well.

"At the time, honestly, I really didn't see it at all, which is the worst thing about suicide. You wonder what you should have done and what you should have noticed."

Rachel's story

Sarah remembers her daughter Rachel's diary entry from when she heard about Harry's death: "This has happened to a boy in my school. I feel so sorry for his family. I could never do that to my family."

Only a few weeks later, Rachel, also 16, took her own life.

Before she became ill, Rachel was "like a whirlwind" her mother says.

"She was going to a load of sport. She ran... was in the athletics club... was running for the school.

She was also "bright and quite political" and "furious about the latest injustice".

"Every cause she could espouse, in school as well as out of school, she did."

But by the end of Year 9 Rachel had started to experience lethargy, the beginnings of depression and worries about her marks.

Her predicted GCSE grades were very high and she was determined to live up to them. But in the first term of Year 10, coinciding with lots of tests at school to get the pupils used to the idea of exams, she "really went downhill".

Rachel eased off the sport, started to put on a bit of weight and began describing herself as "ugly and stupid and all of these kinds of things which she wasn't".

She had started self-harming and took herself to a doctor, at the insistence of a friend.

"Both her arms she'd cut quite badly and she kept it hidden."

The local child and adolescent mental health service acted quickly, with regular appointments, but by January Rachel was no better.

"They were worrying about suicide because she had told them she was suicidal and started to suggest she should take medication, started to suggest that she might need to go into hospital," Sarah says.

Rachel was prescribed the anti-depressant fluoxetine but, soon afterwards, made her first suicide attempt.

The family had set up a watch, Rachel's uncle and aunt more or less moved in to make sure someone was up all night and they saved her.

The doctors immediately took Rachel off the fluoxetine. She attended the adolescent unit at London's Newham hospital as a day-patient, until being allowed back to school in April. But she didn't really get much better.

"She would say she couldn't bear it," Sarah says. "She struggled with noise and chaos, school generally."

A series of overdoses meant that in December 2016 her medication changed again - this time to sertraline, a similar type of drug to fluoxetine.

Sarah believes Rachel's major suicide attempts coincided with changes to her medication. (She wrote about her daughter's ordeal, external after the inquest into her death.) Changes to Rachel's close medical team at about the same time meant she wasn't as honest with them, says Sarah.

Just before Christmas, Rachel took an overdose near a river, after which she was sectioned.

But after returning home, more self-harming and another overdose meant she was never long out of hospital. Rachel's mother and father phoned each other constantly to check where she was.

On the Monday after the start of term, Sarah says, Rachel went into school.

"She left school at lunchtime, which generally they are allowed to do in those years, and that's when she killed herself in the park."

The inquest found Rachel had died by suicide - but Sarah disputes the coroner's conclusion that nothing could have been done differently to save her daughter.

"She really struggled for a long time. I do think the medication was part of the reason. I think it destabilised her a lot."

A safer place

Rose White (left) and Sarah Finke (right) have been able to support each other

The north London comprehensive Harry and Rachel attended is huge, with some 240 pupils in each year group.

The bereaved mothers had never met but when Rose heard what had happened to Rachel, she left a frank note for Sarah.

"Just to say, 'This is shit but if you want to talk about it...'"

"And I did want to," says Sarah.

"It's just the worst thing for a parent," she says, "that your child has killed themselves, that you could be such a terrible parent that your child, A) doesn't want to live, and B) you didn't look after them."

Rose agrees that "the sense of guilt and shame and trauma does make you quite isolated".

"So it is really comforting in a strange sort of way, just to have somebody who knows what it feels like."

There was also massive support from the wider community, who "kind of held and supported us".

"People were really happy to let me talk about Harry and were not judgemental," says Rose.

The school laid on extra counsellors for students, there were pens and paper and they were able to write, and red boxes where they could deposit their notes anonymously if they wanted to.

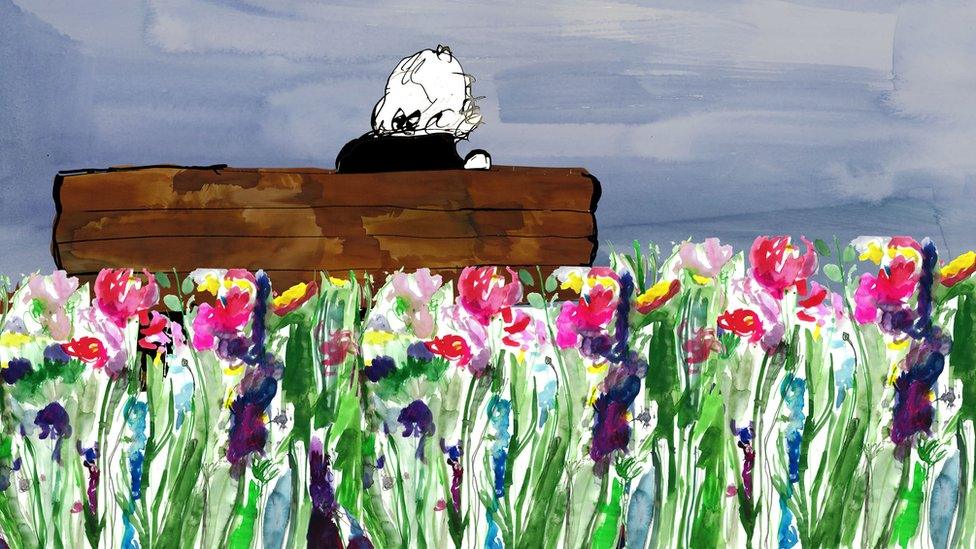

One of Harry's friends set up an online fundraiser for a bench and a tree in the park, aiming for about £500. But the amount donated was soon well into the thousands and the money was eventually used to establish a charity, Safaplace, external, which Rose and Sarah are helping to run.

"I felt a massive responsibility for Harry's friends," Rose says. "I was just really worried about the copycat thing. I felt really awful for them so it felt important initially to be doing something that would support them in school.

"There's the whole thing about this senseless loss and trying to make something, anything, positive come out of it."

The bench in Harry's memory is now in the local park. There's also a new garden for anyone who needs a bit of quiet, in the school grounds. And the charity has hosted a conference on teenage mental health.

Even before the terrible events of two years ago, the mental wellbeing of pupils and staff was a priority for the school. But Rose and Sarah want to go further, taking the support offered in school into the wider community "and perhaps the school becoming a hub for mental health awareness and support", Sarah says.

She sees two major areas where services could be stronger. The first is picking people up early and encouraging them to talk, she says. "And that perhaps would be more the case in Harry's situation than it was in Rachel's.

"So I think to some extent, for me, the stuff that's related to Rachel is about making school more aware and more bearable for kids... and putting more in place once you are ill, because it doesn't stop with raising the alarm."

Simple things could really help, she says, such as making sure schools have up-to-date lists of mental health help-lines - and that these phone numbers are answered.

If the charity develops the way they hope, they want to be able to help other schools to do the same.

"Part of it is to protect others going through awful experiences and part of it is to build on the support of the community," Sarah says.

"My life feels ruined quite a lot of the time," says Rose. "If we could stop anyone else having to go through this, that would be wonderful."

A lasting impact

The latest available UK-wide figures show in 2017, 207 15- to 19-year-olds killed themselves.

Bernadka Dubicka, who chairs the Royal College of Psychiatrists' child and adolescent faculty, says suicide is a tragedy for the individual who takes their own life, with "a lasting impact on family, friends and those who have provided care".

"Anti-depressants are part of a range of treatments for severe depression which include psychotherapy," says Dr Dubicka

She adds that Prozac (fluoxetine) is recommended in national guidance from the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as the first antidepressant that can be offered to young people with moderate to severe depression if psychotherapy has not worked or if the symptoms are very concerning.

"Where it has failed, NICE recommends sertraline as an alternative. NICE advise that antidepressants should always be prescribed alongside psychotherapy and monitored closely."

On Xanax, Dr Dubicka says: "Buying substances from the internet is dangerous. It is unclear what is in them and Xanax has massive addictive potential."

For information and advice on these issues, contact:

Papyrus, external on 0800 068 4141, or text 0778 620 9697 or email pat@papyrus-uk.org

Samaritans, external on 116 123 or email jo@samaritans.org

YoungMinds Parents', external Helpline 0808 802 5544

- Published9 May 2018

- Published19 July 2018

- Published19 April 2018

- Published15 March 2018