Nazi salutes, laddish societies - how should universities deal with them?

- Published

How should universities react to a Nazi salute during an anti-Israeli protest on campus?

Should a group calling itself Laddism Reborn, which distributes misogynist literature and promotes heavy drinking, be allowed to affiliate to a student union?

These are some of the thorny questions that university and student union officials have to weigh up when balancing their legal duty to protect free speech and meeting their duty of care to staff and students.

Comprehensive new guidance on lawful free speech, protecting academic freedom and upholding equality has been drawn up by the Equality and Human Rights Commission, in collaboration with 10 leading organisations including the Department for Education.

It comes just after Warwick University drew criticism for lessening the punishment of students who admitted their involvement in a group chat that threatened rape after an appeal.

However, the National Union of Students (NUS) said that while there is no evidence of widespread difficulties with free speech on campus, the guidance would help tackle the myths about problems of dealing with free speech.

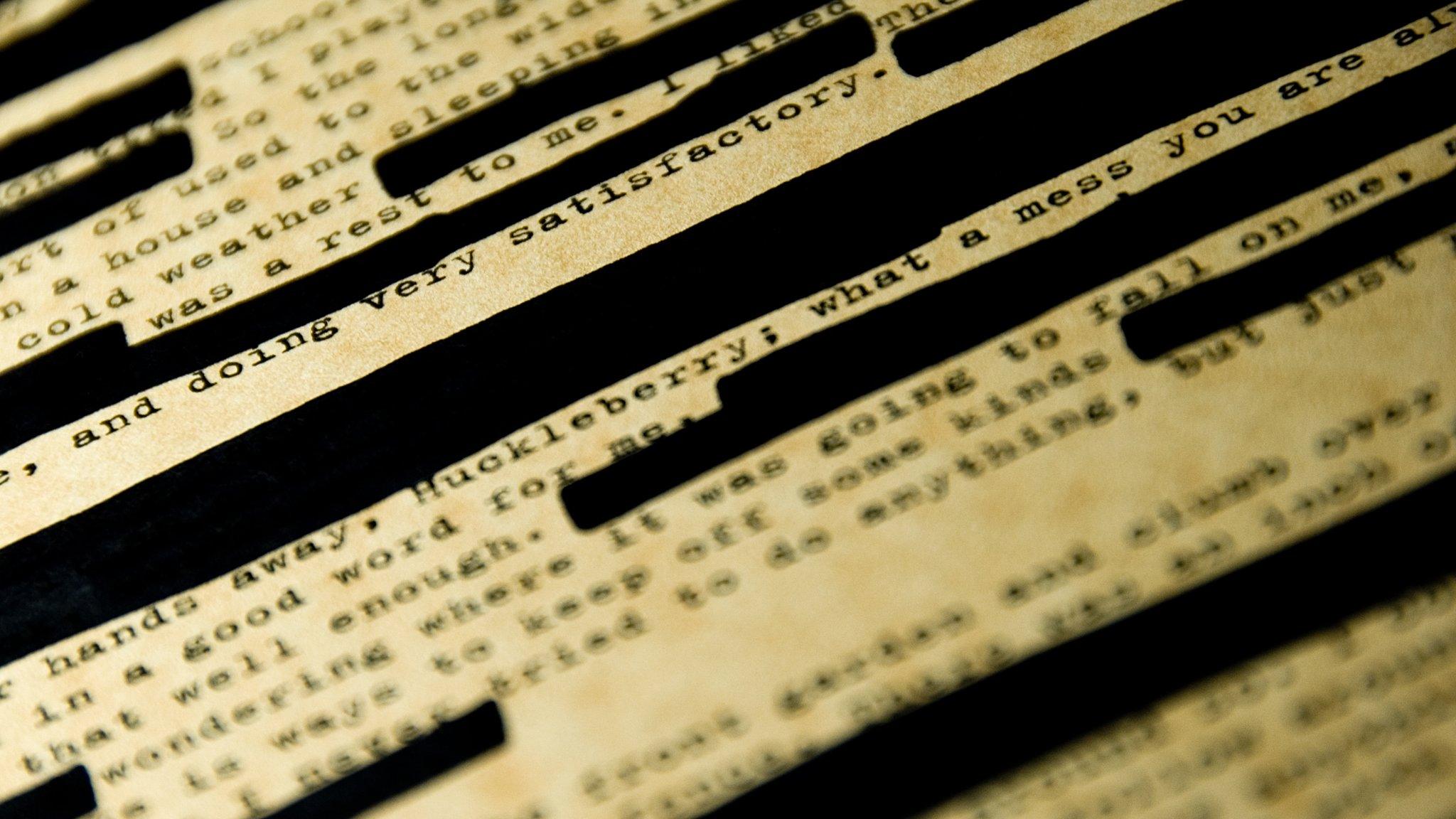

Entitled, Freedom of Expression: a guide for higher education providers and students' unions in England and Wales, it tackles the tricky issue of how student unions and universities deal with controversial speakers, protect their students from "hate speech" and uphold freedom of expression.

And it looks at decisions about allowing so-called "safe spaces" where people with protected characteristics, such as women or ethnic minorities, are able to gather free from the threat of harassment.

Why is this guidance necessary?

Universities have for decades hosted students organising rallies, counter-events and staging sit-ins to protest about issues they hold dear.

Under law, everyone has the right to express and receive views and opinions, including those that may "offend, shock or disturb others".

Higher education bodies have a duty to take all "reasonably practicable" steps to allow individuals to express their views during such protests or events.

But complaints are often made and counter-protests mounted when offensive views are expressed on campus.

This can lead a university authority to feel pressured into cancelling events or restricting protests.

The guidance seeks to set out the position in law.

Clashes of duties

While universities have a duty to protect rights to free speech, they must also balance that against the risk of criminal offences.

This means visiting speakers can be prevented from attending, for example, if there is a high risk that they may use "hate speech" that could incite racial harassment or racial violence or even terrorism.

The right decision about such issues and events may seem obvious, but the fictional case studies given in the guidance suggest officials are having to tread a thin line between the two duties.

The guidance specifically states that higher education providers must have particular regard to their duties around free speech, when carrying out their duties under counter-terrorism laws.

Last month the Oxford Union was criticised for inviting far-right French activist Marion Marechal-Le Pen to speak

At the same time, institutions must comply with the public sector equality duty.

These include eliminating discrimination, harassment and victimisation, ensuring equal opportunities for people who share relevant protected characteristics.

They must also encourage good relations between those with protected characteristics and those without.

This requires them to consider the potential impact on students who might feel vilified or marginalised by any views expressed.

No-platforming

The practice of "no-platforming" has attracted a lot of media attention, but according to the guidelines it is often misunderstood and misreported.

The NUS has a "no-platform" policy which prevents a set of listed organisations, known to hold racist or fascist views, from speaking at its events.

But this policy does not extend to individual student societies.

So if a society invites an individual from such a group, and the student union, or other students, attempt to stop them from speaking, it is down to the university to assess whether the person's freedom of expression is being breached.

Safe spaces

Some student unions have "safe space" for certain groups whose characteristics are protected in equality law.

Safe spaces have been cited as a reason why freedom of expression may be restricted, although few examples have been found.

The guidance says the creation of safe spaces are lawful, but care should be used that they are not applied in a "blanket manner" across the campus, where they may limit freedom of expression .

So how should a university deal with a Nazi salute and an Israeli flag being defaced at a protest?

According to the guidance, university security officers would be right to allow such a protest to happen if no-one is threatening violence or disorder against anyone specific.

But some people have complained about the Nazi salute and argued that the defacing of the flag is anti-Semitic, so they should be stopped.

It could be argued that these were public order offences and or incitement to religious or racial hatred.

According to the guidelines, if the student responsible for these actions was just an individual, removing them from the protest and allowing it to continue, would probably "strike the right balance between preventing unlawful acts and protecting free speech".

- Published18 January 2019

- Published23 October 2018

- Published10 January 2018