How tuition fees change real-life decisions

- Published

Isabella says that if fees are cut, she will go to university, otherwise she will opt for an apprenticeship

Isabella is at a crossroads.

The sixth former from Suffolk has to decide between university or an apprenticeship.

But her choice is not about what she most wants to do - it is being narrowed by her financial fears and in particular her worry about debt from tuition fees.

"I'd like to be able to go to university because it's what I want to do," she says.

But instead it's a decision based on "what I'll have to do because of money".

At the moment, despite preferring the opportunities and social experience of university, she is heading towards an apprenticeship.

Fee decisions

Isabella, part of a group of teenagers being supported by the Villiers Park social mobility charity, has a real-world, life-changing decision that will depend on the outcome of the government's review of tuition fees in England.

If the fees were to be cut to £5,000 or £6,000, she says it would make a "massive difference" to the level of debt and she would switch to applying to university.

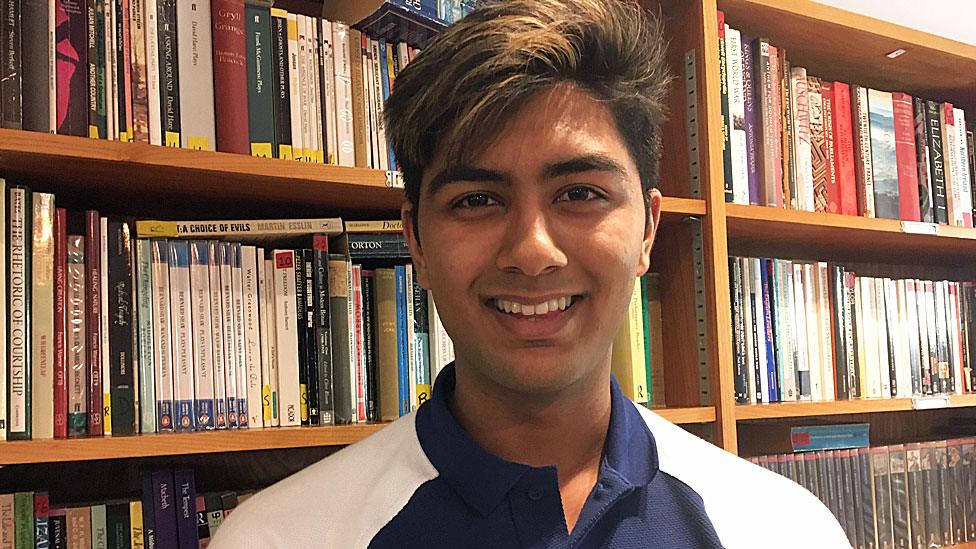

Vrishank says young people are worried about student debts being a "burden on their shoulders"

Articulate and pragmatic, she sees it as a fact of economic life that the current system gives more choices to those "who have the money".

She says she would "definitely" like to opt for university, and its chance to build her confidence and live independently, but her perception of the scale of debt remains too big a risk.

"I don't know where I will be in the future, I don't know if I'll be struggling with money," she says, and so she is looking to an apprenticeship as a practical back-up.

Both of her options are in the balance.

But it could all be changed by the review of student finance, headed by financier Philip Augar, which is expected to report back in the next month.

What do those most likely to be affected think about fees?

Villiers Park is an educational trust working with high-ability teenagers from low-income families - and these youngsters, who are thinking about whether to apply to university, see high fees and debts as a major deterrent.

'We don't live in an ideal world'

"It's demoralising - maybe not for those who are higher up in society, but those who are struggling financially, they're the ones who are hit the most by this," says 17-year-old Vrishank.

"Fear is a big part," he says, with youngsters thinking student debt will be a "burden on their shoulders throughout their whole lives... It's a stain on them".

Maya says families might not want to admit that they cannot afford to support their children at university

Until former students earn £25,000 they will not have to make repayments - and debts will be written off after 30 years - but such relief several decades away does not cut much ice with these teenagers.

Vrishank says fees of £9,250 are a "huge amount" and should be much lower, but he does not expect them to be scrapped.

"In an ideal world, we'd like them to free, so everyone had access to get the education they need... But we don't live in an ideal world, so we have to pay," he says.

The current system has been defended as not deterring poorer students. More young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are going to university - although there is still a wide gap in entry levels between rich and poor families.

But suggestions that there is a level playing field are stridently rejected by these teenagers.

They say see their friends' decisions being strongly influenced by financial worries.

"There is a still a massive inequality, it's there from the beginning of life," says Isabella.

'Costs too high'

It is not only about whether to apply to university, it is also about the range of options.

"I have friends who are specifically not going to London because they know the costs are too high and they won't be able to pay for them," says Maya, a 17-year-old from Leicester.

Many people have given up on university "because their parents can't fund them", she says.

Harry says that tuition fees are part of a wider generational divide, with young people paying the price

But Maya says these families are not going to admit it is about a lack of money.

"They won't say it's about the fees, they'll say I don't want to go.

"It's not just a decision you make when you're older. 'OK, mum will I be going to university?' You kind of know as you're growing up."

Wealthier youngsters are on a parallel educational fast track of "more tutors, more resources, more work experience, more contacts", says Maya.

In terms of what should happen to fees, she is also not expecting them to be completely removed.

"But I do think they should be reduced as the amount that people are having to pay is ridiculous," she says - and suggests a fairer level would be about £5,000 or £6,000.

'Such a divide between generations'

Harry is at school in Belfast, but he's thinking about applying to university in England, and would be affected by any changes in fees.

He says choices are being restricted by financial necessity rather than being driven by talent or ambition.

"What you personally want to do is go to the best university you can," but instead he says young people are limiting their horizons because of cost.

Harry touches on something else that strikes a nerve with all these teenagers - a strong sense of generational unfairness.

These teenagers see tuition fees as part of a bigger set of grievances, with high housing costs, economic insecurity and Brexit all added to the list.

"There is such a divide between generations," says Harry.

"There is a difference between people making the decisions and those who are going to have to suffer the effects," he says.

"We pay the consequence for our elders' decisions," says Vrishank.

- Published23 January 2019

- Published2 November 2018