Will universities go bust if fees are cut?

- Published

- comments

There's a growing expectation that the review of student finance in England, headed by the financier Philip Augar, is going to recommend a cut in tuition fees.

The first figure floated, £6,500, seems to have drifted up to £7,500 after complaints from universities - but that would still be significantly less than the current maximum of £9,250.

With some universities already facing precarious finances - with borrowing, recruitment problems and emergency bailouts - there are claims that institutions will be at risk of collapsing.

Shadow education secretary Angela Rayner says the government needs to "get real about the consequences of a university going bust".

But how likely is it to happen?

Are universities really in financial difficulty?

What makes universities really nervous is that a reduction in fees will not be replaced by direct funding from the government.

Even if funding is promised, it will make universities dependent on the goodwill of politicians, competing with other spending pressures, such as health and schools.

Universities are worried that a cut in fees will not be replaced by an equivalent in direct funding

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute and former universities minister special adviser, says the rule of thumb is that every cut in fees of £1,000 will take about a billion away from the current funding stream.

If there is a significant cut in per student funding, he says, it will "push some to the wall".

As well as a loss of fees, he says universities face a "perfect storm" - with a demographic dip in the number of 18-year-olds and Brexit casting a shadow over recruiting international students.

There are universities already on financial thin ice - in debt over new buildings and then struggling when they fail to attract students.

And if a university has a terrible year for recruitment, they have three years of teaching that reduced cohort and its smaller income.

Dr Greg Walker, chief executive of the MillionPlus group of new universities, warns if funding for students is cut, or there are limits on numbers, there are risks of "significant damage".

"Difficult choices could well have to be made," he said. But he said undermining university finances would be a "national own-goal".

Even without changes to fees, is the university sector going to eat itself?

Sir Anthony Seldon, vice-chancellor of the University of Buckingham, and an influential figure in the politics of education, says there is already a "serious risk that some universities will go under".

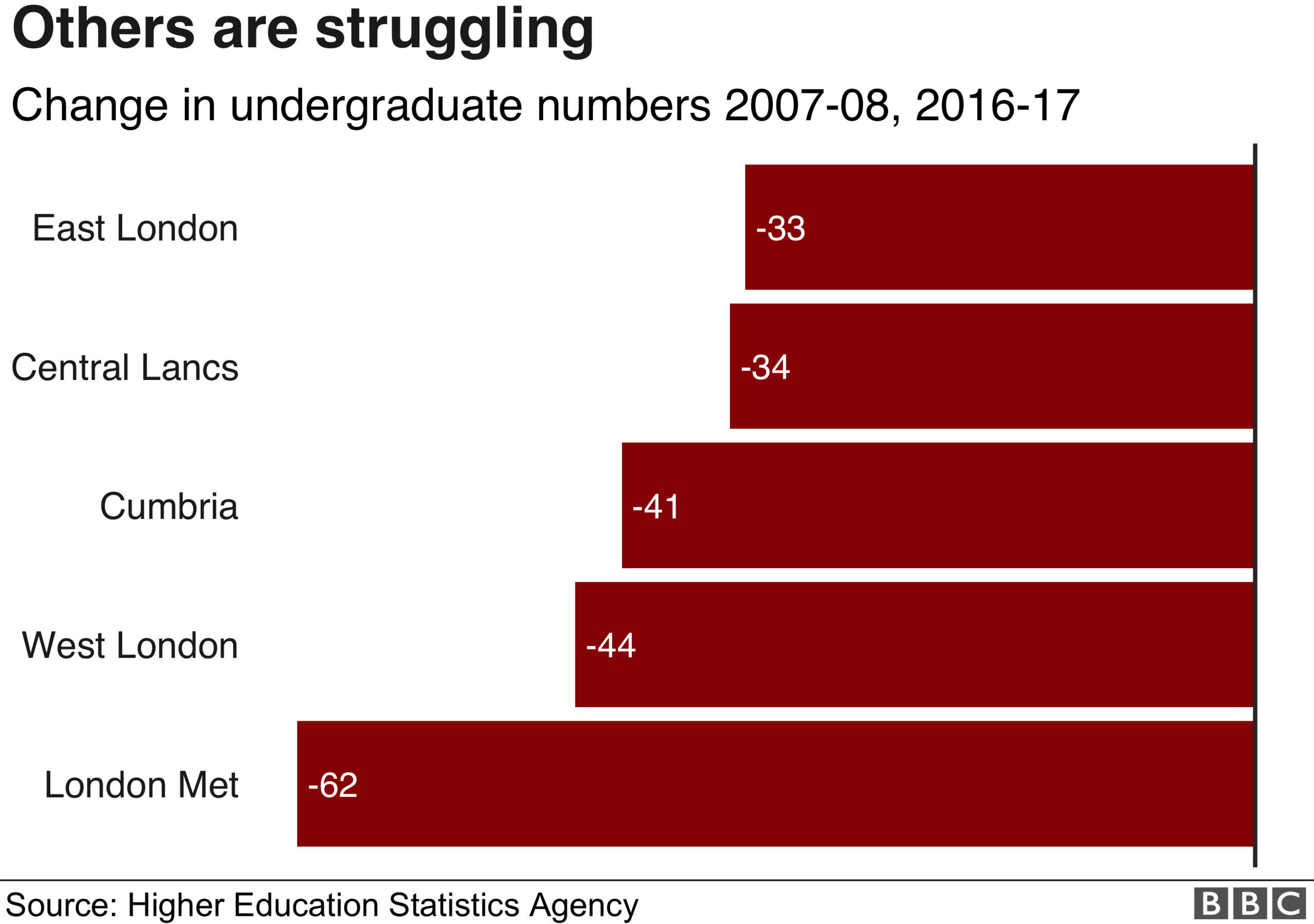

He warns that the aggressive expansion of some "juggernaut universities" is pushing others out of business.

There are a finite number of students - and if some universities take an ever-rising number, others will be left starved of fee income.

Sir Anthony attacks a "greedy cohort" for threatening the higher education "eco-system".

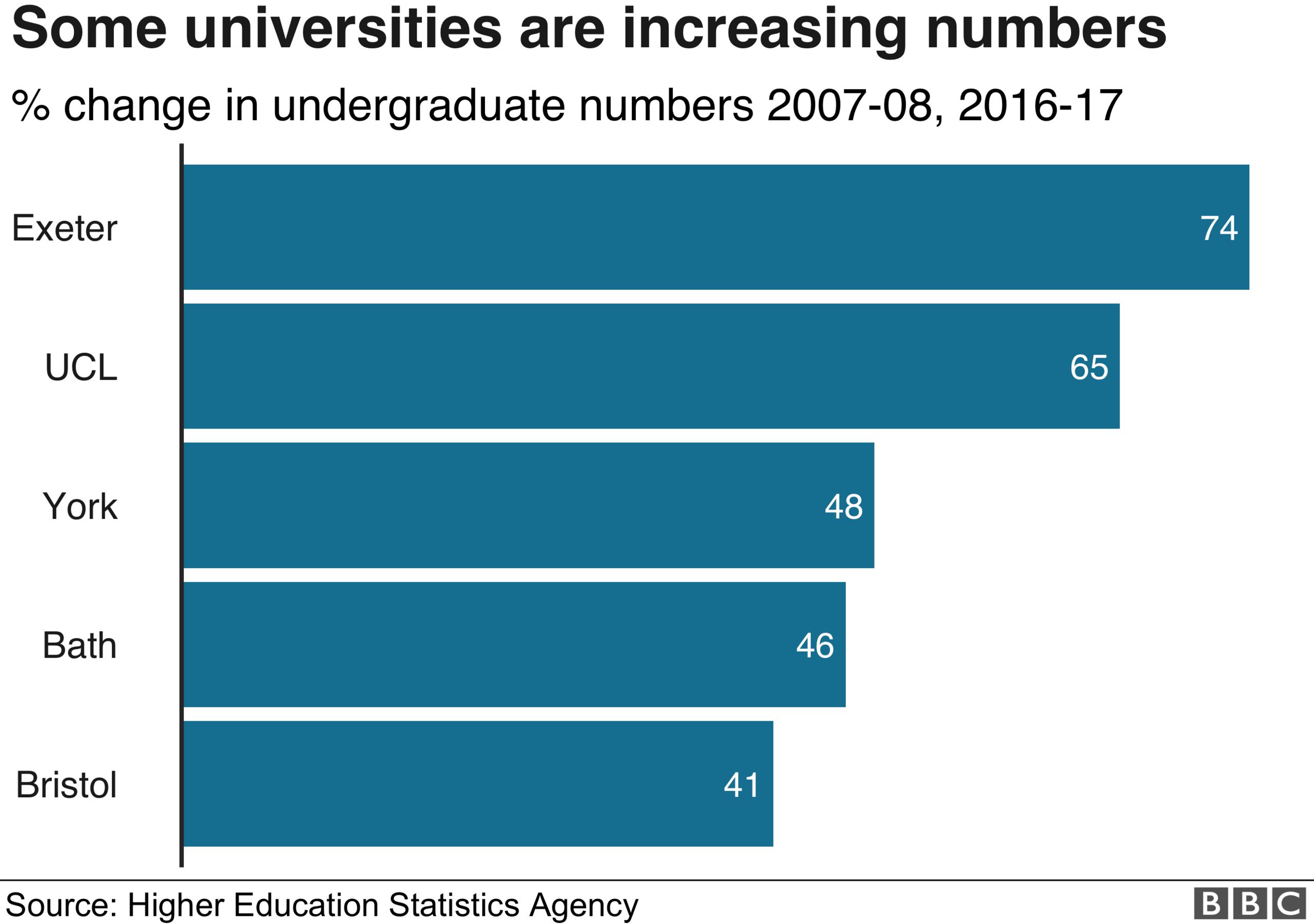

Figures from the Higher Education Statistics Agency show some universities have piled on extra students, while others have shrunk.

Over the past decade, Exeter University has expanded its undergraduate numbers by 74%.

University College London has grown by 65%, York 48%, Bath 46% and Bristol by 41%.

But London Metropolitan University has shrunk by 62%, with the University of West London down by 44%, Cumbria by 41%, the University of Central Lancashire by 34% and University of East London by 33%.

If this process continues, Sir Anthony says it will threaten the future of some universities.

But the University of Exeter rejects the criticism, saying it is "proud of its growth" and expanding has allowed more people to get places, rather than being turned away "because of our lack of space".

Would universities be allowed to collapse? Or are they too big to fail?

Ministers and regulators have always kept to the script that they will not intervene.

Last week, Universities Minister Chris Skidmore, said: "There is an expectation that in a small number of cases providers may exit the market altogether as a result of strong competition."

But Hepi director, Nick Hillman, says the risks of a financial crisis will not be shared evenly, and it's likely to be survival of the biggest.

Sheffield is now a city of students rather than steel at the centre of the local economy

Only smaller institutions would be allowed to fail.

Big universities are major employers, anchors of the local economy, and the legal and political fallout from closure would be too toxic, he says.

Above a certain size, he says, "the government cannot let a university fall over".

A report last week from the UPP Foundation's civic university commission showed universities' pivotal place in regional economies.

In Sheffield in 1978, it says "there were 4,000 students and nearly 45,000 people working in the steel industry".

"Today there are around 60,000 students and around 3,000 steelworkers."

It seems unlikely that where universities have become so central that they would be allowed to go under.

Would going bust really mean shutting down?

Mergers or take-overs are more likely than shut downs, so that students could carry on, even though the name of the institution might have changed.

Universities, as part of their registration with the Office for Students, have to produce a "student protection plan" showing how students could continue with their studies even if their university or course closed.

Even if universities buckle financially, they would still have a long stretch before hitting the rocks.

"The capacity to cope with decline can vary," says higher education adviser Louis Coiffait.

Some universities could trade for a long time on the value of their assets, such as land or property, with sell-offs giving them enough of a "war chest" to fund a recruitment drive and recovery, he says.

Could the fees review make universities more financially stable?

Dr Walker says if the review could reverse the decline in part-time students that would mean a significant improvement particularly for new universities.

"The right recommendations could rocket-boost support for prospective students wishing to study flexibly," he says.

A switch from fees to direct funding, without an overall loss of budget, could give universities a more stable income, less vulnerable to unpredictable levels of recruitment.

But if fees are lowered, perhaps for autumn 2020 or later, there are are fears about a sudden drop in university cash flow, as students would be likely to postpone starting.

As such the review is being urged to include a phased approach to any changes.