Inequality driving 'deaths of despair'

- Published

Widening inequalities in pay, health and opportunities in the UK are undermining trust in democracy, says an Institute for Fiscal Studies report.

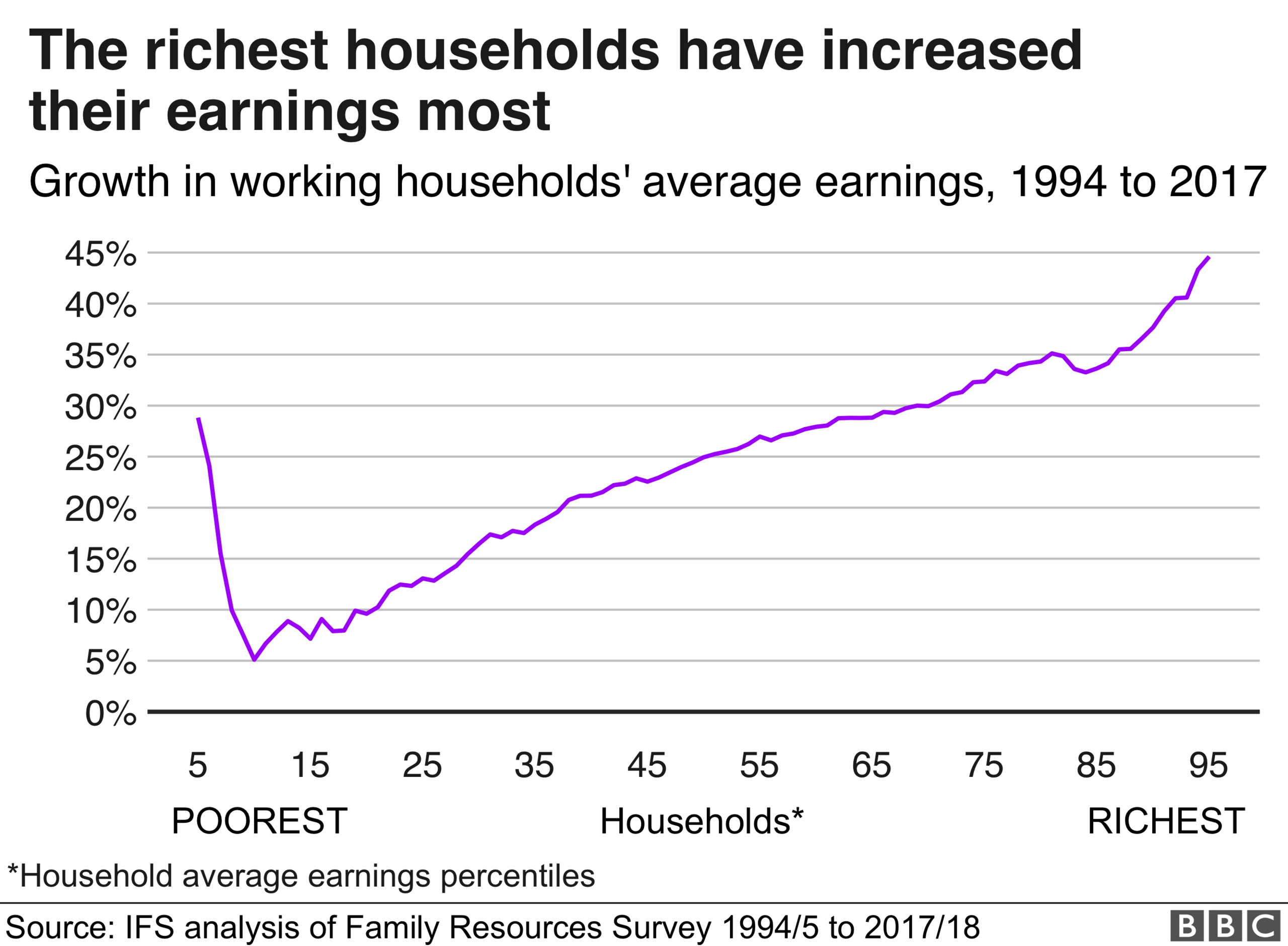

The think tank warns of runaway incomes for high earners but rises in "deaths of despair", such as from addiction and suicide, among the poorest.

It warns of risks to "centre-ground" politics from stagnating pay and divides in health and education.

The report says such widening gaps are "making a mockery of democracy".

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), one of the country's leading research institutes, is launching what it says is the UK's biggest analysis of inequality.

That will be chaired by Nobel Prize-winning economist Prof Sir Angus Deaton.

'Taking rather than making'

He said "people were troubled by inequality" more than at any time since the 1940s - and the impact was so serious that it suggested "democratic capitalism is broken".

He warned of the dangers of disillusionment if people did not feel fairly rewarded for their work - and that extreme wealth seemed to be gained by "taking rather than making".

Sir Angus said "people getting rich is a good thing" but not if it meant "enriching the few at the expense of the many".

At the outset of this review, the IFS has published indicators of inequality - such as the average chief executive of a FTSE 100 company now earning 145 times the average salary, up from 47 times in 1998.

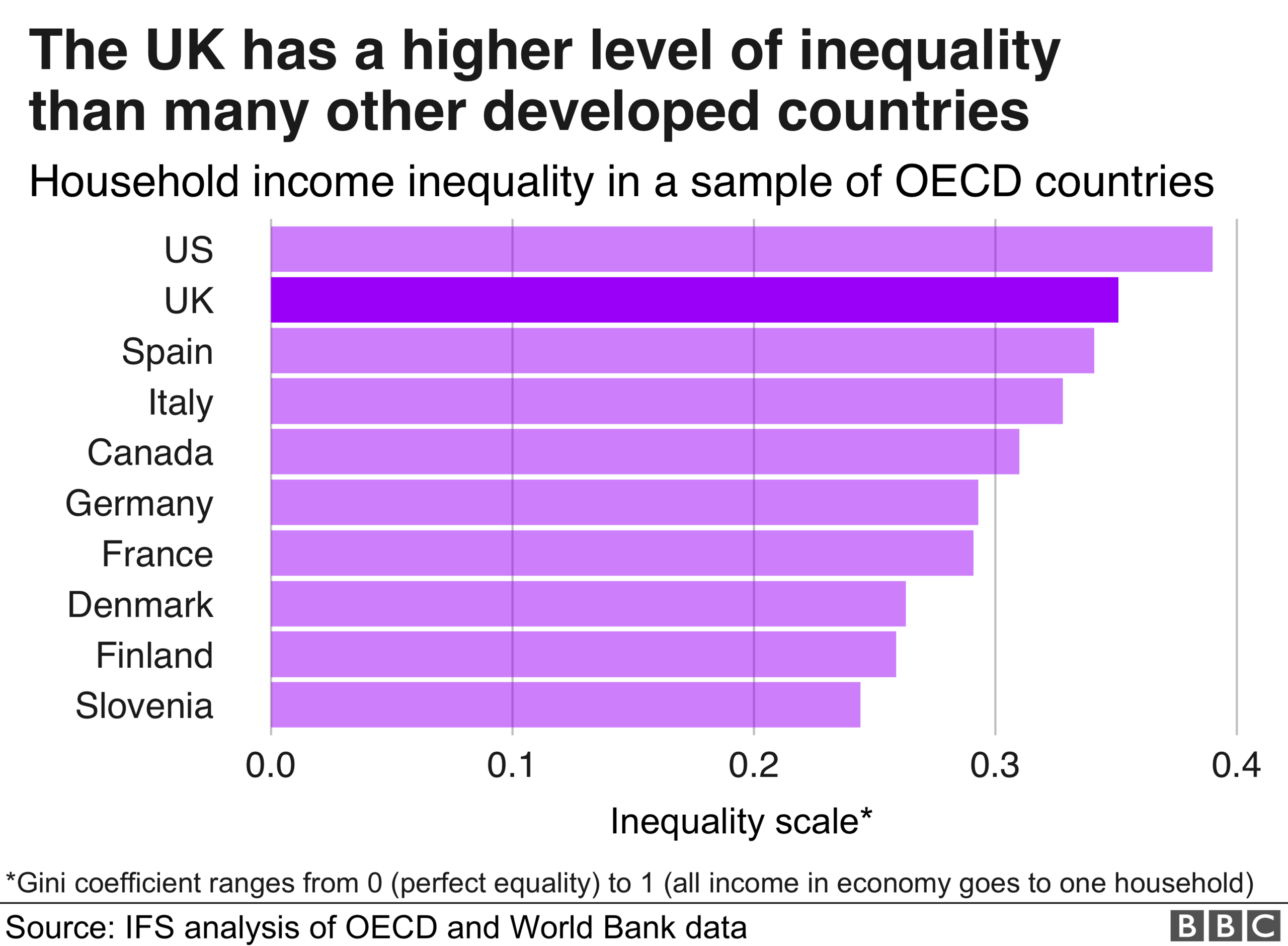

It suggests pay inequality in the UK is high by international standards - with the share of household income going to the richest 1% having tripled in the past three decades.

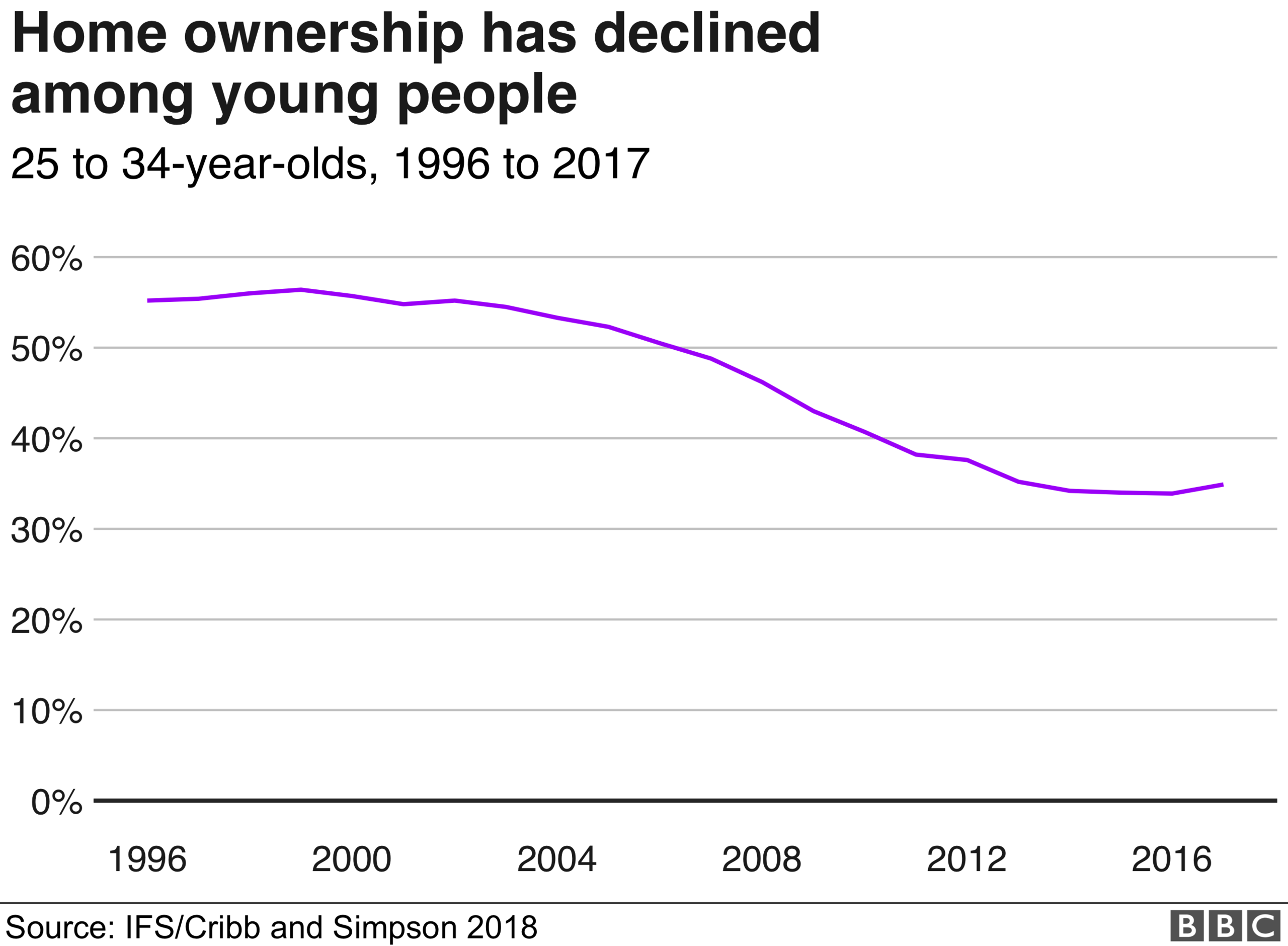

The middle classes are also under pressure, particularly younger generations, with stagnant pay and unaffordable house prices.

The long-term decline in trade union membership is identified as another factor in wages not increasing.

As well as inequality in income, the think tank highlights divergence in health.

It says there is almost a 10-year gap in male life expectancy between the richest and poorest areas - and the IFS warns of "deaths of despair", with a rise in early deaths from drug and alcohol abuse and suicide being linked to factors such as poverty, social isolation and mental health problems.

Patterns of relationship are also affected by inequality, the study suggests.

Over recent decades, wealthier people have become more likely to be living in a couple, either married or co-habiting, the IFS says.

But among the poor, declining numbers are living with a partner, a pattern attributed to increasing job insecurity, a lack of financial independence and more "chaotic lives".

The big picture, says the IFS, is the UK is becoming more like the US, with a concentration of wealth at the top and pressure on working families lower down the pay scale.

'Inequality of political voice is even worse', says Prof Sir Angus Deaton

It says that in the US, increases in life expectancy have stalled and that for non-graduate male workers, pay has not risen in real terms for five decades.

"The risk is that the UK may follow a similar path," says the IFS study.

The IFS warns of the social tensions that will come with an economic landscape built on widening inequality.

As economic think tank the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reported recently, this is likely to put pressure on the middle classes as well as those on low incomes.

'Constant lack of security'

James Hutchinson says if people do not feel they are making progress, they become "disconnected"

University science researcher James Hutchinson, in his 30s, feels he has kept his side of the bargain - gaining a degree from Cambridge - and now working as an academic as well as raising a family with his partner.

But he feels a sense of "powerlessness" about the cost of housing and that his work has no job security, with a series of short-term contracts.

"It's not a sob story," says Dr Hutchinson, "But if people feel they can't improve their lot, then they feel disconnected."

"We were sold the idea that academic success is the way to be better off," he says.

His partner Bethany has decided not to work because she can't afford childcare. She says "for me as a parent, I didn't feel comfortable with us being separated... and then working all hours."

Bethany and her partner James Hutchinson have struggled to make ends meet for their family

They live in Bristol and struggled to get somewhere they could afford to live - currently the family all sleep in one room while they patch up their home.

Dr Hutchinson recognises that he's "more privileged than many" - earning the average for UK graduates of £35,000 per year - but he voices a frustration at a lack of progress and fears that things could get even worse for his children.

The "disconnect" comes, he says, from his generation becoming "increasingly aware of your own expendability" and a work culture haunted by a "constant lack of security".

Dr Hutchinson is sceptical that any of the political rhetoric will translate into real improvements.

"How do we build a functional society out of dysfunctional lives?" he asks.

The consumer society is afraid of becoming the consumed.

- Published10 April 2019

- Published28 March 2019

- Published8 April 2019