If GCSE exams get harder, how can results go up?

- Published

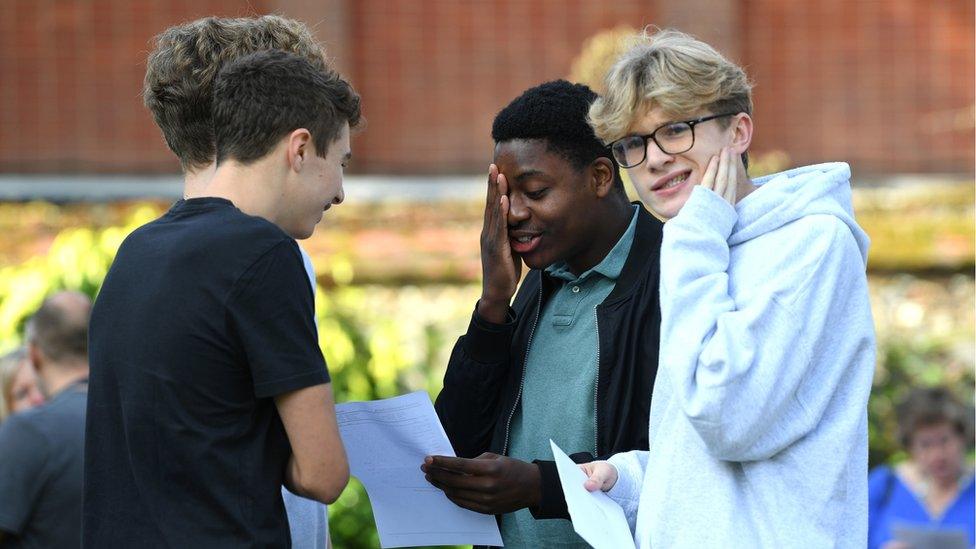

After all the warnings about GCSE exams in England getting harder - how have the results gone up rather than down?

Or more to the point - how have they really remained the same?

The pass rate across England, Wales and Northern Ireland has gone up from 66.9% to 67.3% - which, when you round it up, means it has gone all the way from 67% to 67%.

The results for England alone were even more constant, with only a 0.2% flicker of difference.

Smooth on the surface

This is not an accident, but reflects the smoothing mechanism that keeps the overall results very similar.

It is called "comparable outcomes" and it is a bit like academic air-conditioning. If the results are bubbling upwards, the cooler kicks in to bring things down to the same level again.

The intention is to keep the results fair over time.

If exams have been made more difficult, such as in the last couple of years, it would not be fair if pupils got terrible results compared with previous years.

The balancing mechanism to stop this happening is to shift the grade boundaries - so that for a difficult exam, the pass mark will be pushed lower.

But to achieve this apparent stability on the surface, it can mean some strange outcomes down below at subject level.

For instance, for one exam board this year, the pass mark for the maths higher paper was 22% and 27% for higher physics.

It means for maths, a pupil can get about four out of five questions wrong and still emerge with a pass.

But for English Language, the requirement for passing with the same grade and same exam board, was 52%.

Constant by design

What makes this particularly counter-intuitive is that we want to think about exam results as something that could change unpredictably - like temperatures going up, or sports results or exchange rates.

For the individual students, they might do better or worse - but for the overall results, the system is constructed and calibrated to produce continuity.

This can create tensions. In 2012, there was a court case brought by teachers and a local authority claiming that grade boundaries had been manipulated in a way that was unfair to pupils taking GCSEs in English.

The case was lost, but it raised the potential for conflict between the outcome for individual students and the workings of the overall system.

Grade inflation

Cynics might also look to a political dimension to all this - and how exam results have delicately shadowed changes in policy.

When Labour were in power, they pointed to the endlessly improving exam grades as welcome evidence of their investment in schools.

Every year, GCSE and A-level results could only get better.

In opposition, the Conservatives attacked these rising results as "grade inflation" and promised to change it.

Since they entered office, grades have stayed very similar, despite a major overhaul of the exam system.

Instead, the government has quoted Ofsted grades as its chosen metric of success - and the proportion of schools getting good and outstanding has climbed steadily.

Of course this might raise the question as to why, if so many schools have improved, they do not get better exam results - but that again runs up against an exam system that is currently set on a steady outcome.

- Published22 August 2019

- Published22 August 2019