How women students put a rocket up Cambridge

- Published

A penny rocket firework thrown at women campaigning in 1897 to be able to graduate from Cambridge University

Women's long struggle to gain fair access to university is commemorated in an exhibition opening next week at the University of Cambridge library.

What's most shocking, perhaps, is that it's all so relatively recent - with women not allowed to graduate from Cambridge on equal terms until 1948.

For teenagers currently filling in their university applications, it would be hard to imagine that within living memory at Cambridge there was such blunt discrimination.

The "Rising Tide" exhibition shows the level of resistance, including violence, against women wanting to study at Cambridge with equal rights to men.

Until 1948, women were not able to graduate from the University of Cambridge

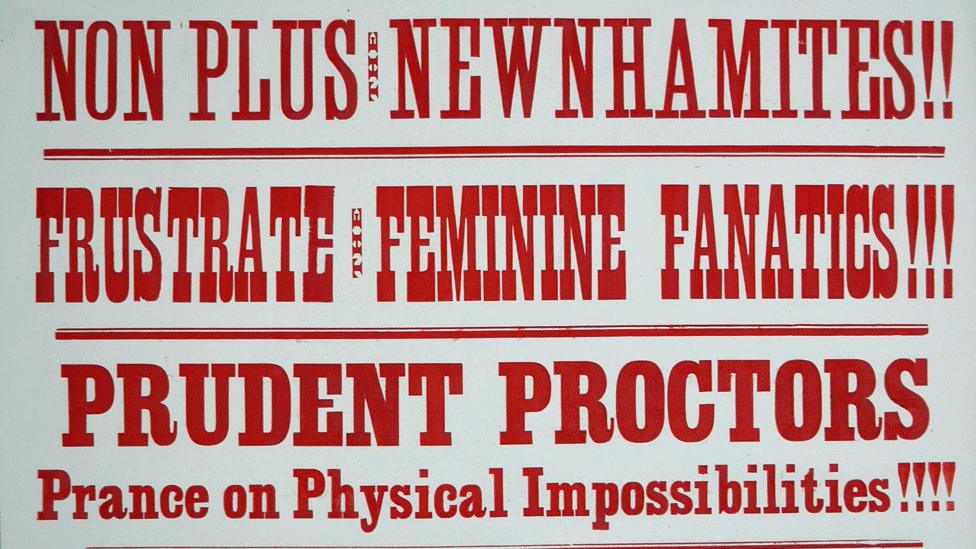

This includes the remnants of a firework thrown by protesters in 1897 as they rioted against the revolutionary idea of women getting degrees.

But in the end it was the women who put a rocket up Cambridge, rather than the other way round.

Radical change

If Cambridge was slow to allow women to graduate, it had been a pioneer in admitting them to university, and the exhibition marks the 150th anniversary of women being able to study at the university's Girton College.

This initial admission of women to the university was seen as extremely radical and controversial.

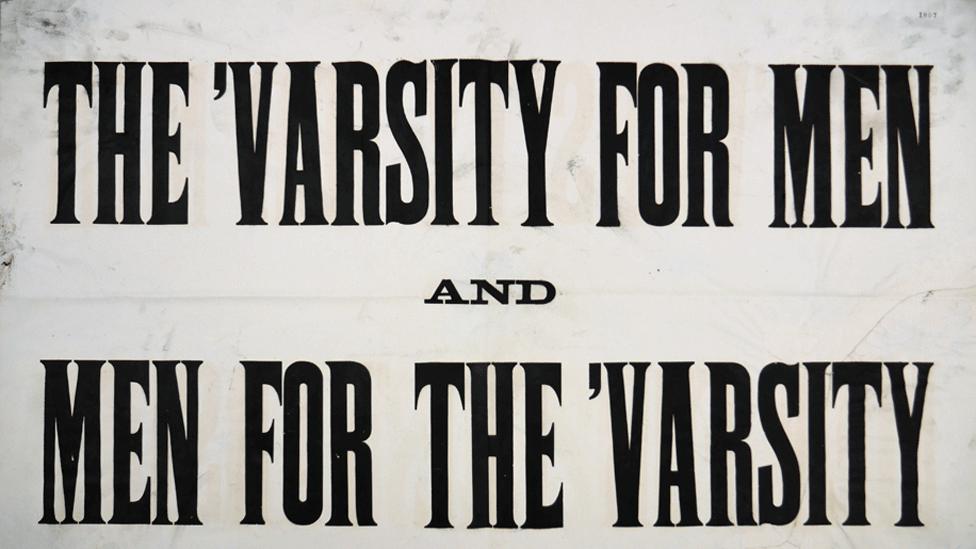

There were angry campaigns by former students opposing reformers who wanted women to be able to get degrees

"It was an extraordinary idea," says Lucy Delap, a historian at Cambridge and curator of the exhibition.

But she says this was only the beginning for women wanting to get an "education on the same terms as men".

It wasn't until the 1880s that women could take the same exams as men, says fellow curator and historian, Ben Griffin.

And women students didn't get the right to attend lectures until the 1920s.

A painting by Caroline Walker of female scientists has been commissioned for the exhibition

The battle didn't end with the right to graduate with a degree in 1948, as Dr Griffin says the university still operated a quota limiting female students until the early 1960s.

'Intellectual power'

When the first women arrived at Cambridge in 1869, he says it bore little relation to a modern university.

Only a handful of subjects were taught and the only people permitted to graduate were male members of the Church of England - and Dr Griffin says much of the university was essentially an "Anglican seminary".

It meant that as well as women, all other religious denominations and everyone who didn't have the funding to pay for university was excluded, which meant the vast majority of the population.

The gown on the left was worn by a "steamboat lady" who collected a degree in Dublin - and on the right a tennis dress from the 1880s

The arrival of women, marching into Cambridge wearing gloves and hats and guarded by chaperones, was an academic earthquake.

"There was a question mark about their intellectual character. Are women's brains the same as men's? Can they absorb information in the same way of lectures and essays? Do they have the intellectual power to be here?"

Dr Delap says these were the type of challenges from an establishment suspicious of change.

'Injustice'

But the female students more than proved a match, coming top in exams, even though they were not able to graduate.

"This seemed such an injustice, they're ahead of the men but they're not getting degrees and the honours that men are getting," says Dr Delap.

This was used as evidence in the battle for women to get the vote in parliamentary elections.

But the push for women to become graduates, backed by a public petition, was not accepted.

"The people who fiercely opposed it were former students," says Dr Griffin - and they had a vote in Cambridge's decision-making.

The first female recipient of a degree was the Queen Mother, who received an honorary degree in 1948

In 1897, a vote on women getting degrees turned into a riot, with opponents throwing fireworks and eggs at the reformers.

Another vote in 1921 also blocked women's right to graduate, with the victors celebrating by vandalising Newnham College where women studied.

'Steamboat ladies'

This created some bizarre anomalies, with women employed as academics, including a professor by the 1930s, while still not allowed to get a degree.

Others walked away, switching to places such as the London School of Economics or universities in the United States.

But there were creative efforts to get around this discriminatory barrier.

Women produced their own degree certificates, which Dr Delap says could be much bigger and more ornate than the documents given by the university.

"They were giving themselves DIY degrees," she says.

There were also hundreds of Cambridge women, between 1904 and 1907, who graduated via Trinity College Dublin.

These so-called "steamboat ladies" used an arrangement that allowed them to collect degrees from Dublin - before that back-door route was also closed.

This wasn't only about proving a point, Dr Delap says this was a practical document for women in jobs such as teaching.

Overturning assumptions

By the late 1940s, the refusal to give women degrees had become indefensible and there was almost no opposition to its removal. Fast-forwarding to the present, many more women now go to university than men in the UK, so the gender gap for undergraduates is about the lack of male students.

Cambridge's modern intake of new students

The exhibition's curators say it shows how much attitudes can be transformed and that assumptions which we now hold will also be overturned.

Arguments about inclusion and exclusion, continuity and reform, rights and injustice will continue.

"It's about the possibility of change," says Dr Griffin.

"The arrangements we're used to are not fixed or timeless, they can change too. It should be a hopeful that thing that institutions can change and are changing all the time," he says.

The Rising Tide: Women at Cambridge exhibition from 14 October, University of Cambridge Library

- Published26 September 2019

- Published9 September 2019

- Published27 September 2017