Overhaul exclusions to beat knife crime, say MPs

- Published

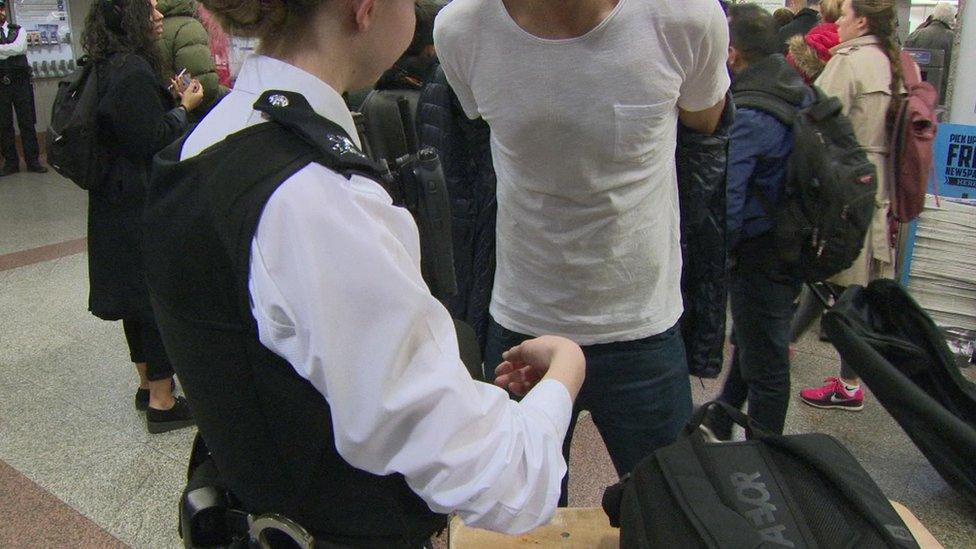

Excluded teens are "easy pickings" for criminal gangs, says a group of MPs and peers

Better support for excluded pupils could help stem the rise in knife crime, a report from a cross-party group of MPs and peers has found.

Too many excluded pupils get only a couple of hours teaching each day, says the report.

There is evidence this leaves them at risk of being drawn into knife crime, it adds.

Ministers warned that "simple causal links between exclusions and knife crime cannot not be drawn".

However, research by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Knife Crime found only a third of councils were able to confirm they had space for newly excluded pupils in their pupil referral units (PRUs).

And the report, Back to school? Breaking the Link between School Exclusions and Knife Crime, urges the government to ensure councils give all excluded pupils full-time, high quality education.

Tipping point?

The MPs and peers heard evidence that pupils who are not found places or are only taught part-time have more opportunity to get into trouble.

"Since they kicked me out, I've got time on my hands to... commit more crime in Croydon with my friends who have also been kicked out, who are also doing wrong things, who are also selling drugs who are also carrying knives," said one excluded pupil.

Others said their schools had not been very good at supporting them when they were on the cusp of trouble, with zero-tolerance policies leading to exclusions for relatively minor offences.

"I would get excluded more often and sent home more often, for unnecessary reasons, like not wearing a blazer, my socks not coming up to my knees. Just silly things like that," said one.

"It is encouraging kids to go out and do what they want because you are not giving them an education."

The report includes official statistics, showing that in 2017-18, more than 17,500 boys aged 14 in England and Wales carried a knife or weapon, with a third of these having had weapons used against them.

Separate statistics for the same year showed permanent exclusions from England's schools stood at 7,900, up 70% on 2012.

By law, all pupils are entitled to full-time education, starting six days after their exclusion begins but "too often this is not happening", says the report.

The researchers sent questionnaires to all of England's 150 local education authorities and received responses from 80% of them.

Of these:

about a third had no spaces in their state-funded alternative provision

about a third did have space

the rest either could not say or did not operate state-funded alternative provision in their area

Croydon Central MP Sarah Jones, who chairs the parliamentary group, called the number of children excluded from school "a travesty".

"Often these children have literally nowhere to go," Ms Jones said.

"They are easy pickings for criminal gangs looking to exploit vulnerable children."

Javed Khan, chief executive of children's charity Barnardo's, added: "Exclusions must be a last resort and alternative education provision must be full-time."

The report calls for a government review into the use of part-time education for excluded pupils and says school rankings and results should take account of all pupils, including those who have been excluded.

The government said ministers would "always back teachers and heads in delivering discipline in the classroom".

"The issues surrounding knife crime and poor behaviour in schools are complicated and multi-faceted," said a spokeswoman.

"We are clear that permanent exclusion should only be used as a last resort and exclusion from school must not mean exclusion from education.

"Furthermore, we must be just as ambitious for young people in alternative provision as we are for those in mainstream schools, and we are taking a range of actions to drive up the quality of those settings."

The Local Government Association said the recent rise in knife crime by young people was of "enormous concern" and councils shared MPs' and peers' concerns.

Judith Blake, chairwoman of the LGA's Children and Young People Board, said councils welcomed changes to Ofsted inspections to take exclusion numbers into account.

"We are also calling for councils to be given the powers and funding to hold all schools to account where there is evidence of unexplained pupil exits," said Ms Blake.

- Published15 July 2019

- Published8 March 2019

- Published7 March 2019