Bad local transport linked to failing schools

- Published

- comments

The study takes a look at school achievement in terms of transport connections

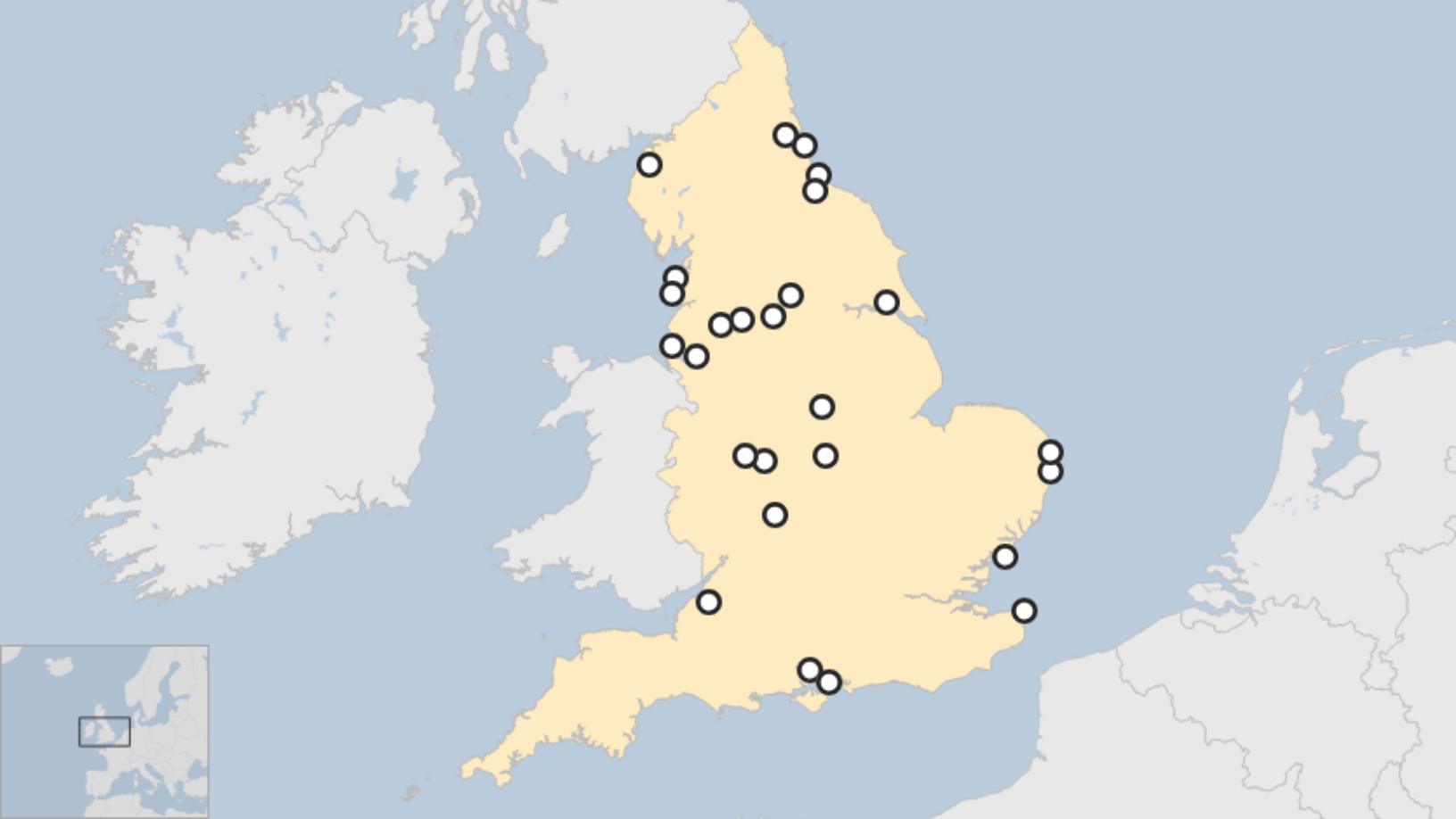

There is a striking overlap between places in England with slow public transport and places with struggling secondary schools, say researchers.

Instead of only looking at education data, researchers compared schools using journey times from the Department for Transport.

They found clusters of bad transport and underachieving schools in places such as Norfolk and north-east England.

Even in richer areas, poor transport seemed linked to lower school results.

The long wait for progress - bad transport seems to overlap with lower secondary school results

In reports on academic underachievement the same coldspots repeatedly recur - such as the "left behind" towns in the north west and north east, declining seaside towns in the south, or along the Norfolk coast.

The study from education analysts, SchoolDash, has examined this pattern not in terms of exam results or Ofsted grades, but from the perspective of transport connections.

Above a map showing clusters of struggling schools and, below, clusters of deprivation and slow transport.

This is not how long it takes pupils to get to school - but how well their local communities are served by buses and trains.

This found that badly connected places were more likely to have low-achieving secondary schools, external.

Trains for brains - faster connections seemed to mean better school results

Even in places without much deprivation, researcher Timo Hannay said "more isolated schools are substantially more likely to under-perform and less likely to be judged outstanding".

Across secondary schools, 31% of those with fast public transport links are graded as outstanding.

Among secondary schools in places with slow travel times, 17% are outstanding.

Where poor public transport is combined with high levels of deprivation, there is a "double whammy", say researchers.

Among all secondary schools, 24% are rated inadequate or requires improvement.

But in schools in deprived areas with longer travel times, there are 66% of schools in these bottom Ofsted categories.

The measurements used are journey-time statistics from the Department for Transport, which show how long it takes by public transport to reach a major centre for employment.

London has high levels of connectivity in transport - and the best school results in the country

The average travel time is 33 minutes - and the researcher's analysis shows how school results seem to worsen as journey times stretch beyond this.

The slow connections are not just the end-of-the line towns on the coast, it can affect the edges of big cities, such as Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol and Newcastle, and pockets of Kent and the south west.

Seaside towns can face a "double whammy" of poor transport and underachieving schools

There are places where deprivation and slow transport overlap, such as:

Great Yarmouth and Lowestoft in East Anglia

Clacton-on-Sea in Essex

Margate and the Isle of Sheppey in Kent

Fleetwood and Accrington in Lancashire

Rochdale in Greater Manchester

Runcorn in Cheshire,

Redcar in North Yorkshire

South Shields and Jarrow in Tyne and Wear

Skegness and Grimsby in Lincolnshire

Bridlington in East Yorkshire

Hastings in East Sussex

In contrast, London has high levels of connectivity in transport - and despite deep pockets of deprivation, some of the best school results in the country.

There is a political dimension to this too.

Boris Johnson's government has promised to invest in transport as a form of economic regeneration, particularly in the north of England.

Places with bad transport suffer from a lack of physical as well as social mobility

In the geography of the last general election, this study from SchoolDash shows the places with poor transport and under-performing schools were the seats where voters swung to the Conservatives.

These are areas where social mobility is held up by a lack of physical mobility.

But why should transport have any link to schools? How could trains mean brains? Or is this just a pattern of multiple, overlapping forms of neglect, without any causal connections?

And is funding of transport part of a bigger picture including inequalities in funding of schools?

Anna Vignoles, a professor in education at Cambridge University, highlights a double impact - with pupils from communities with low horizons and schools where the cut-off location makes it hard to recruit teachers.

"Staffing is key," she says.

The quality of public transport links makes a big difference for access to local jobs markets

A school needs to be in commuting distance to attract teachers, she says - and the location has to be practical for their partners to get to work too.

Prof Vignoles says in a highly-connected city, pupils are "surrounded by clear evidence of good jobs and the value of education".

"By contrast in peripheral and rural locations with little connection to industries and good jobs, it may be harder to see the benefit of education."

Dame Rachel de Souza, chief executive of the Inspiration Trust with schools in Norfolk and Suffolk, says: "Poor transport infrastructure obviously limits the extent to which people are physically mobile, but it can also in some cases be an indicator of poverty of aspirations.

"And of course, added into the mix are the challenges around attracting and retaining staff.

"Coastal areas have their own unique set of challenges, but these need not determine a young person's future," she says.

There has been a growing awareness of regional differences in school results

Simon Burgess, a professor in the economics of education from the University of Bristol, says there is never going to be any "one-cause" explanation for the pattern of schools doing well or badly.

But he says poor local transport can mean there is in effect "zero competition" between schools, with parents unable to choose an alternative.

Timo Hannnay, founder of SchoolDash, says the research supports an "intuitive" sense about places that are "cut off and disadvantaged".

But he says there are more unexpected findings.

It affects secondary but not particularly primary schools, which he thinks reflects the difficulty in recruiting specialist teachers.

He was also surprised to see how soon the isolation factor is felt, including in the outskirts of big cities. "You don't have to be very far away for it to make a difference".

- Published9 July 2019

- Published17 December 2019

- Published12 January 2016