Last survivor of transatlantic slave trade discovered

- Published

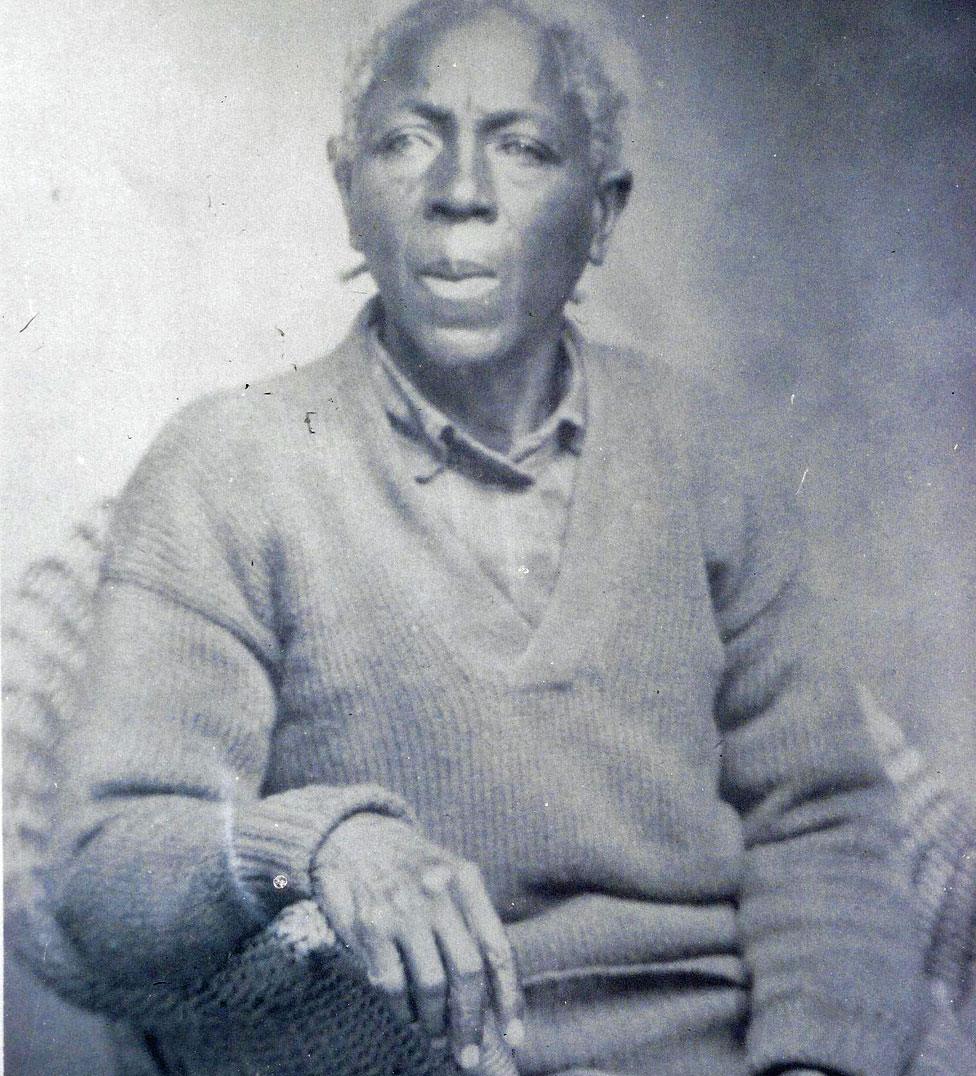

Matilda McCrear lived until 1940 - the last survivor of the transatlantic slave trade

The transatlantic slave trade might seem like something from a distant and barbaric era - but a historian has found evidence its last survivor was alive in living memory.

Hannah Durkin, at Newcastle University, had previously identified the last surviving slave captured in Africa in the 19th Century and brought to United States as a woman called Redoshi Smith, who died in 1937.

But she has now discovered that another former slave, Matilda McCrear, had lived three years later.

Matilda died in Selma, Alabama, in January 1940, at the age 83 - and her rebellious life story was the last living link with slaves abducted from Africa.

Johnny Crear, a witness to 1960s civil rights protests, did not know about his grandmother's life story

Her 83-year-old grandson, Johnny Crear, had no idea about his grandmother's historic story.

In the 1960s, he had witnessed violence against civil rights marchers in Selma, where protesters had been addressed by Dr Martin Luther King.

On discovering his grandmother had been enslaved, he told BBC News: "I had a lot of mixed emotions.

"I thought if she hadn't undergone what had happened, I wouldn't be here.

"But that was followed by anger."

A 19th Century map shows the "Slave Coast" of West Africa

Matilda had been captured by slave traders in West Africa at the age of two, arriving in Alabama in 1860 on board one of the last transatlantic slave ships.

With her mother Grace, and sister Sallie, Matilda had been bought by a wealthy plantation owner called Memorable Creagh.

Dr Durkin says there must have been a dreadful sense of separation, loss and disorientation for these families. Matilda's mother had lost the father of her children and two other sons left behind in Africa.

And in the US she had been powerless to stop two daughters being taken from her, sold to another owner and never seen again.

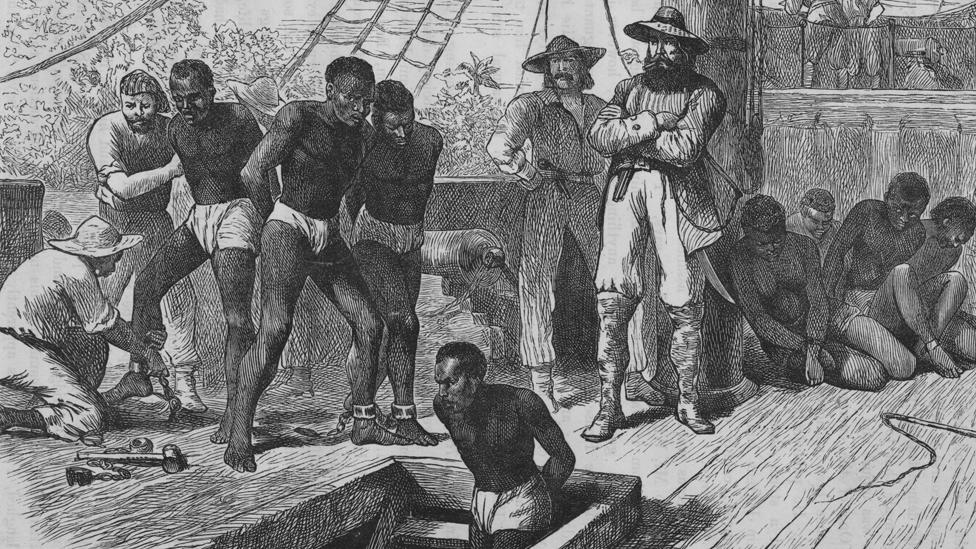

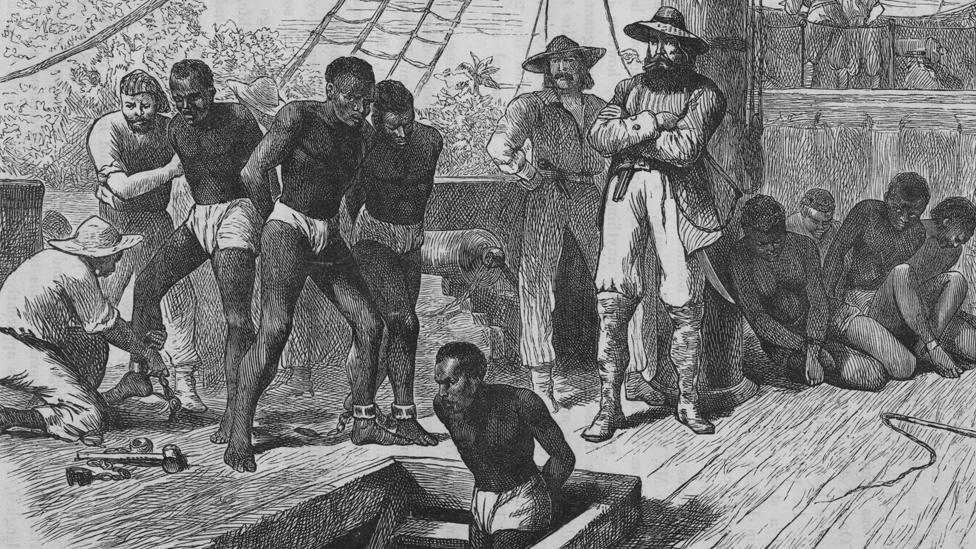

Slave ships continued to bring captives from West Africa to the United States until about 1860

Matilda, Grace, and Sallie tried to escape the plantation soon after they arrived but they were recaptured.

The abolition of slavery, in 1865, brought emancipation but Matilda's family still worked the land, trapped in poverty as share-croppers. It seems Grace did not ever learn much English.

"But Matilda's story is particularly remarkable because she resisted what was expected of a black woman in the US South in the years after emancipation," Dr Durkin says.

"She didn't get married.

"Instead, she had a decades-long common-law marriage with a white German-born man, with whom she had 14 children."

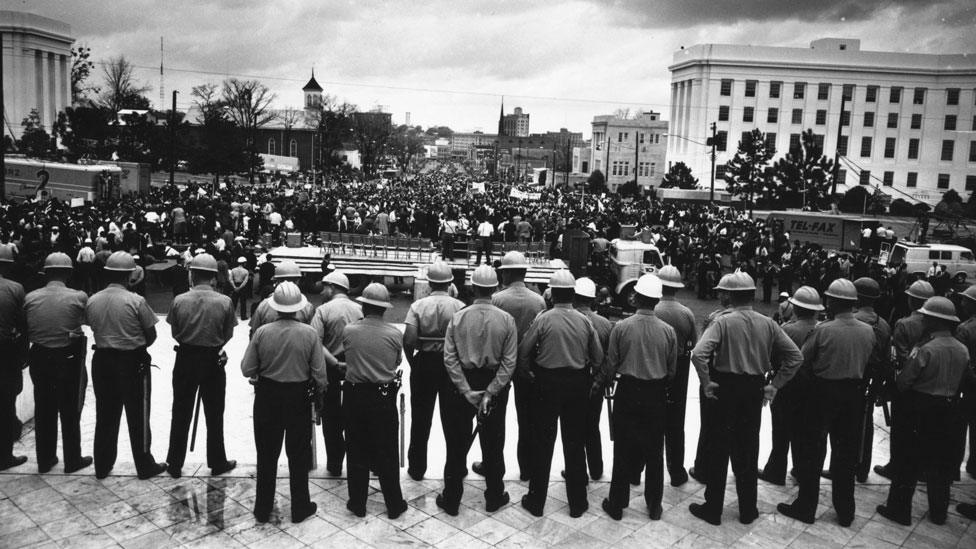

Martin Luther King at a civil rights protest in Selma, in 1965

It also seems likely that her partner was Jewish, says Dr Durkin.

The couple's relationship was "astonishing" for its era, she says, crossing boundaries of race, class, religion and social expectation.

And Matilda changed her surname from Creagh, the slave owner's, to McCrear.

She was remarkably strong willed, Dr Durkin says.

"Even though she left West Africa when she was a toddler, she appears throughout her life to have worn her hair in a traditional Yoruba style, a style presumably taught to her by her mother," says Dr Durkin, whose research is published in the journal, Slavery and Abolition.

She also carried the facial markings from a traditional rite in Africa.

A stand-off between police and civil rights marchers in Alabama, in 1965

In her 70s, Matilda set out on another journey, travelling for 15 miles on dirt roads to a county courthouse to make a claim for compensation for her enslavement.

By then, she was one of a small number of surviving slaves from Africa who seem to have made contact with each other.

There was a settlement near Mobile, Alabama, of descendants of slaves from the same ship as Matilda, where the West African language of Yoruba was spoken.

In the Deep South in the 1930s, this bid for compensation, brought by a poor, black, female, former slave, had little chance of a sympathetic hearing and her claim was dismissed.

But such a provocative idea, reparation for slavery, attracted local press attention and the interviews helped to fill in some details of her life.

Commemorations marked the 55th anniversary of the civil rights marches in Selma

When she died, with the still raw history of slavery remaining a difficult and dangerous topic, there were no obituaries - and no recognition.

"There was a lot of stigma attached to having been a slave," Dr Durkin says.

"The shame was placed on the people who were enslaved, rather than the slavers."

Selma this month, during the vote for the Democratic Party presidential nomination

"I was born in the same house where she died," said her grandson, Mr Crear.

And although his family knew Matilda was originally from Africa, nothing much was spoken about her life.

"This fills in a lot of the holes that we have about her," he says of Dr Durkin's research.

But the cruelty Matilda faced is no surprise to him.

"From the day the first African was brought to this continent as a slave, we've had to fight for freedom," he says.

He grew up in an era of racial segregation - and his parents put a huge emphasis on education as the way to escape poverty and the "key to changing the world".

But the lack of knowledge about his grandmother reflects how much of the history of slavery still lies below the surface.

"It doesn't surprise me that she was so rebellious," Mr Crear says.

The civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery was re-enacted this month

In the civil rights protests, they were singing songs with roots in the years of slavery, he says, tapping into the same "continuous struggle and fight" and pursuing the same the goals of "real freedom and equality" as his independent-minded grandmother.

"It's refreshing to know she had the kind of spirit that's uplifting," he says.

But it is still sobering to think how the glamour of 1940s Hollywood overlapped so directly with the lives of women and children brought in chains from Africa.

- Published3 April 2019