Disruption to schools could continue to November, MPs told

- Published

- comments

The partial closure of schools in England could continue into the autumn and into November, the Commons education committee has been told.

Primary schools opened more widely to several year groups in some areas this week, 10 weeks after they were closed as part of Covid-19 lockdown measures.

Secondaries remain shut and around eight million pupils are out of school.

David Laws, chair of education charity EPI, said assumptions all pupils will return in September may be wrong.

The committee was hearing evidence on the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on education and children's services.

'Immense loss'

Mr Laws, also a former education minister, said: "There's a temptation to think we are in a kind of home learning now and hopefully all back in September. Sadly we may end up with considerable disruption to school in September, October and November."

He urged ministers to make plans and give guidance to schools for "a situation where there may be some home learning for a lot of pupils for a very long time".

Anne Longfield, the Children's Commissioner for England, highlighted that eight million pupils were currently out of school, despite limited opening of primary schools this week.

She said the sheer scale of children not reaching their potential because of this lockdown would be immense.

"That could be eight million children all of whom could well be out of school for six months."

'School drop-out fears'

And she warned as more of society and many parents go back to work, there would be a fall-off in the numbers of those engaging in learning from home.

"As things become more interesting, the shops will be open soon and many kids could spend two and half months browsing in Primark and not going to school."

She added that head teachers had told her they were kept awake at night by fears about some children never returning to school.

The leap that children who had had a negative experience of school would have to make, in order to return to school, would be "vast", she said.

The committee was told the Department for Education needed to publish its guidance on how schools would look in September very soon.

And plans for catch-up summer schools, which were backed by witnesses, needed to be set out by ministers soon, if they were to happen.

Attainment gap

The hearing comes as a report suggested school closures could wipe out 10 years of progress in closing the achievement gap between poor and rich pupils.

Modest estimates in the government-commissioned report suggest the shutdowns could cause the gap to widen by around a third of what it is now.

This could mean poorest primary pupils, who are already nine months behind, slipping back a further three months.

The Education Endowment Foundation study said catch-up tuition would help.

The charity's research also warned of a risk of high levels of absence after schools formally reopen and that this posed a particular risk for disadvantaged pupils.

The rapid evidence assessment drew together evidence on 11 studies from a number of countries on the impact of school closures, focussing on those which looked at learning loss over the summer holiday period.

It found the estimated impact on the gap between the poorest group of pupils, and their wealthier peers ranged widely from 75% to 11%.

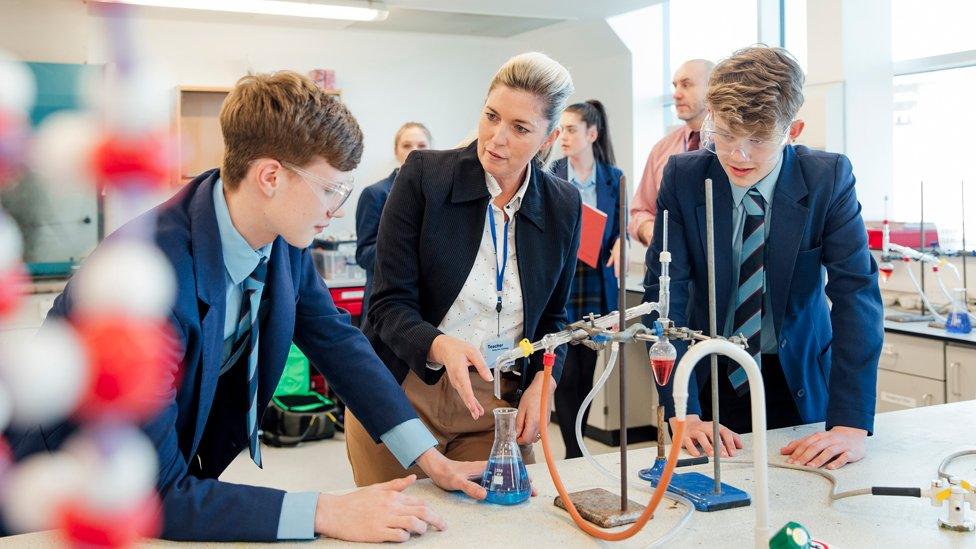

Chemistry experiments are difficult to replicate at home

The median estimate was 36%, although the researchers said there was high level uncertainty about this average.

The report is published days after a small proportion of the school population returned to lessons.

Although effective remote learning would limit the extent to which the gap widens, the report said there would still need to be sustained support for disadvantaged pupils to catch up.

Over the past decade, the Department for Education has focused attention and resources on closing the disadvantage gap.

It has narrowed from 11.5 months in 2009, at the end of primary school to 9.2 months in 2019.

'Deeply unfair'

Sir Peter Lampl, chairman of the EEF, said: "School closures are likely to have a devastating impact on the poorest children and young people. The attainment gap widens when children are not in school.

"There is strong evidence that high quality tuition is a cost-effective way to enable pupils to catch up."

His organisation has teamed up with a number of other organisations to run a trial in which 1,600 disadvantaged pupils around England are offered one-to-one and small group tuition.

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson said being in school was vital for children's wellbeing.

He added: "This innovative online tuition pilot is an important part of our plans to put support in place to ensure young people don't fall behind as a result of coronavirus, particularly those facing disadvantages."

Russell Hobby, head of teacher training charity Teach First, described the potential loss as "tragic".

This should start with intensive catch-up provision when possible, he said, adding more resources need to be targeted towards those pupils who have suffered the most.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

IMPACT: What the virus does to the body

RECOVERY: How long does it take?

LOCKDOWN: How can we lift restrictions?

ENDGAME: How do we get out of this mess?