Housing crisis: The 59-year-old woman who lives in a van

- Published

Polly has lived in a small campervan for more than a year

"I don't want to live like this, no-one should live like this - but I don't have any options," says Polly Richardson who finds herself at the sharp end of the lack of affordable homes in England.

For more than a year, she has lived out of a small camper van.

"This is my home. I've two sets of clothes in a box. I've got my cups and saucers in this drawer, my pans under this bed, and I have a little camping cooker.

"Winter time was horrendous because there was no heating."

The 59-year-old grandmother of four from East Yorkshire is one of half-a-million households that aren't even counted as waiting for a council or housing association property, according to the National Housing Federation.

New research commissioned by the Federation from Heriot-Watt University says the real number of people in England waiting for such homes is 3.8 million, representing 1.6 million households, or 500,000 more than is indicated by official government data.

"I've got belongings in people's garages," says Polly.

She spent years working as a retail manager but after taking time off to look after her sick father, and then having a big argument with her sister, she found herself being forced to move into the van in March 2019.

"Without a job, you can't have a house. Without a house, they won't give you a job. I'm hoping somebody out there will give me a job," she says.

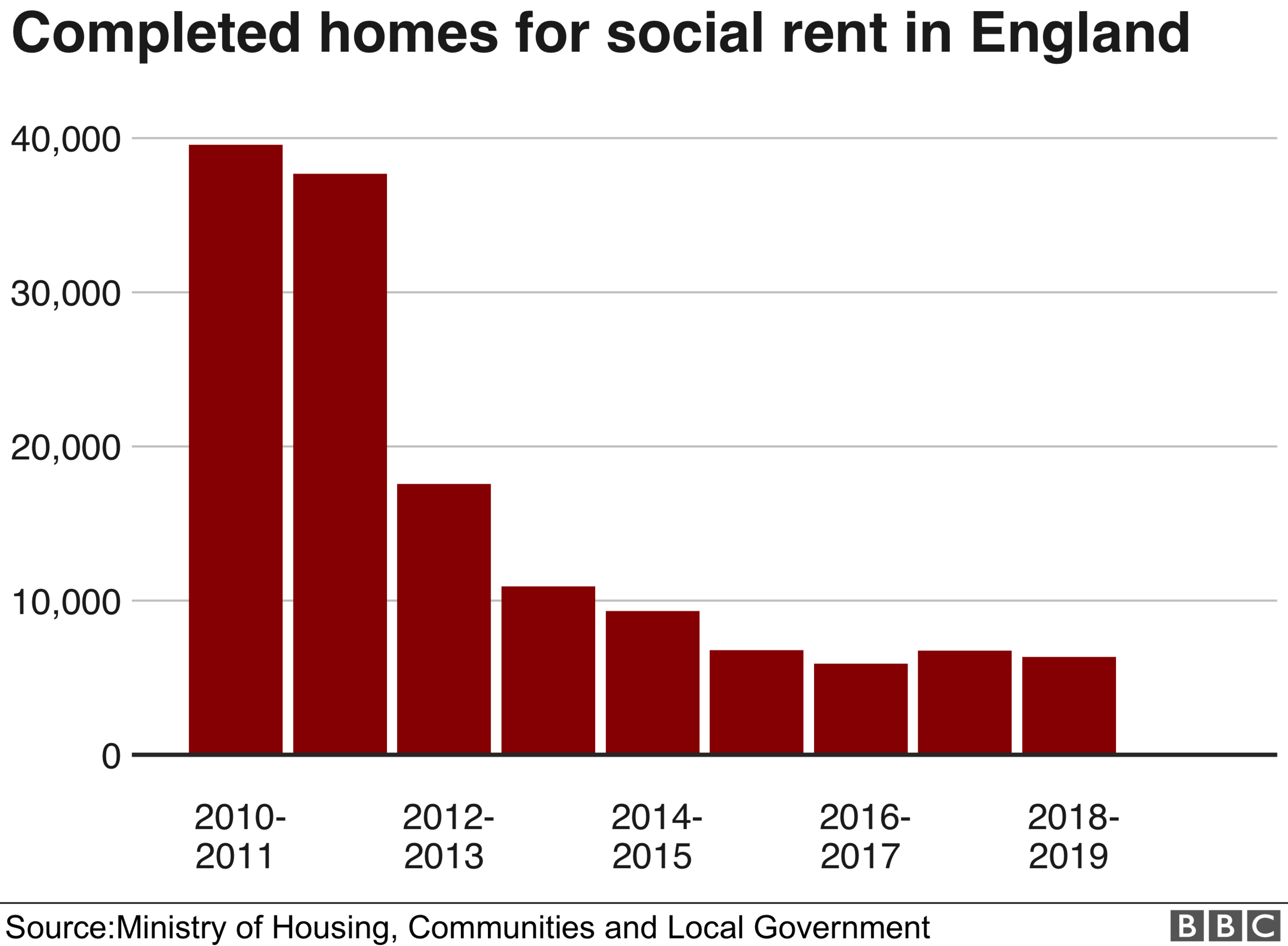

The National Housing Federation say 90,000 homes for social rent need to be built each year for the next decade to meet demand but, according to official figures, just 6,338 such homes were completed in 2018-19, down 84% since 2010-11.

The main advantage of social housing - where either the local council or a housing association are the landlord - is that it's more affordable than private rented accommodation, typically around 50% of market rents, and usually offers a more secure tenancy.

"What we are seeing is an escalating need for social housing and a lack of supply," says Kate Henderson, chief executive of the National Housing Federation.

"Investing in social housing would boost the economy, it would create thousands of jobs, it would support supply chains in the construction industry and it would provide better, more secure, safe housing for people in need."

The lack of suitable properties leaves large numbers of families living in overcrowded accommodation.

Abigail McManus, a 27-year-old single mother lives in a two-bedroom flat in Leeds with her three young children - two daughters aged six and two and a little boy who's five months old.

Leaving her house is a daily grind as she struggles to manoeuvre her double buggy down the stairs.

Abigail has been bidding weekly for a three-bedroomed ground floor property for years, without success.

She says the council are encouraging her to search further afield to increase her chances being allocated somewhere suitable to live.

But she says: "My whole family live on this estate, so I'd like to try and stay as close as possible.

"As a single parent, who doesn't drive, it would be hard for me to get anywhere and I'd feel more isolated than I already do, if I move too far from this area."

Mum of three Abigail McManus struggles to get her double buggy into her flat

When she was prime minister, Theresa May altered the way in which councils could use funding to allow them to build more homes.

Her government predicted the change would lead to 10,000 new council houses each year, a figure that hasn't been reached since 2013-14.

While local authorities believe building that number is possible, experts say the pandemic could create problems in the construction industry.

The Ministry of Housing said it "didn't recognise" the figures in the new analysis carried out by the National Housing Federation, describing them as a "major overestimation".

It also highlighted its £11.5bn investment in affordable homes, to be spent between 2021 and 2026, some of which will be used on building homes for social rent.