Home-schooling around the world: How have we coped?

- Published

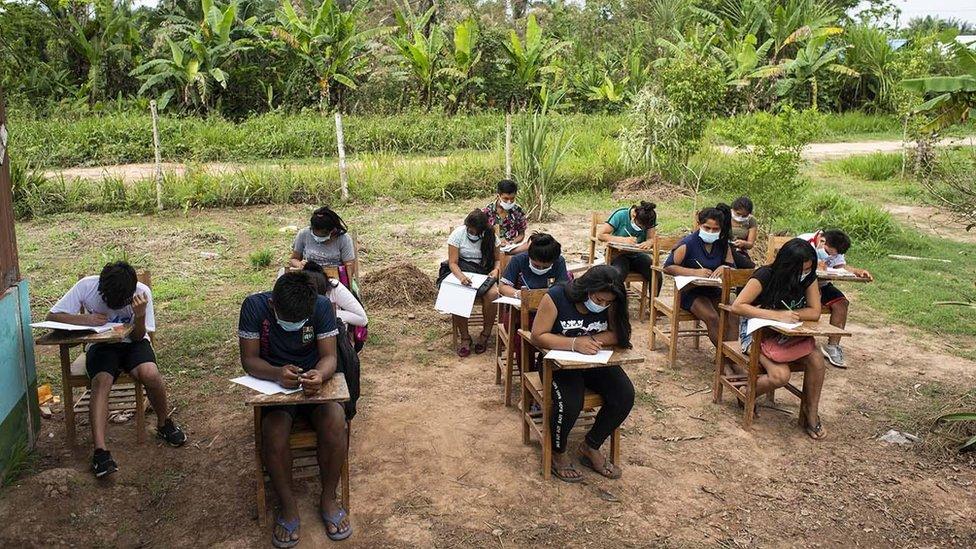

Children throughout Peru have been hindered by limited access to internet

When Covid-19 shut schools across the world, few imagined that more than a year later millions of children would still be stuck at home.

And although school closures have been far and wide, the experience has been anything but universal for pupils, parents or their teachers.

'Groceries and therapy'

In the US, parents in Washington DC were initially told their children would need to home-school for two weeks. More than a year later, mother-of-two Lori Mihalich is only now beginning to see an end in sight.

"It has taken a toll on both my husband's and my own mental health," the 41-year-old tells the BBC. "We joke that almost all of our income now goes to groceries and therapy bills."

While concern about her children's learning was initially high, as the months went on, Lori's focus shifted towards the mental health of her children, aged 8 and 10.

"I admit to not realising exactly how much support, not only academic but also physical and emotional, school provided my kids. Having consistent childcare has been the biggest struggle, and the unpredictability of each day has definitely ramped up my own anxiety in unhealthy ways each day."

Schools in many parts of the US are beginning to open their doors to students again. But the same cannot be said just a few hundred miles away in South America - a continent that has seen more school closures than anywhere else in the world.

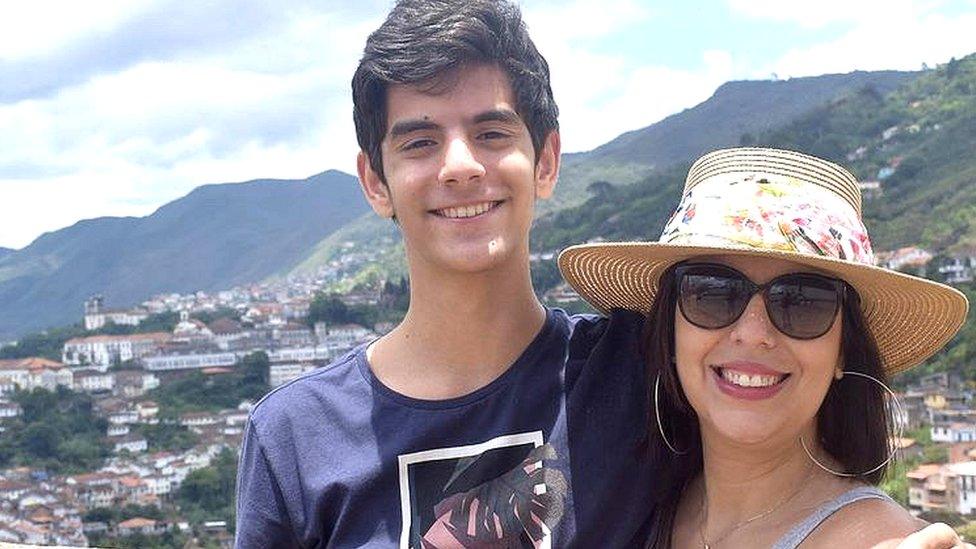

Carolina Campos, 40, lives at home in the city of Recife, in north-east Brazil, with her 16-year-old son Arthur. Schools there closed in March 2020 and only began to reopen in January this year.

But with a new Covid-19 variant emerging in the country, closures are now happening for a second time.

Carolina lives in Brazil with her son, Arthur

"I suffered a lot initially and needed therapy twice a week," Carolina says. "My son felt very sad, and his school didn't offer enough support."

She became so unhappy with the quality of her son's remote learning that she pulled him out of class and enrolled him in a private school. However, Carolina knows her experience is not one shared by most families in South America.

"I'm a privileged, white, middle class woman," she says, "there are countless poor and undereducated mothers who have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic."

She says she is certain the pandemic has "only exacerbated the learning inequality that already existed".

Digital disparity

UNICEF, the UN agency responsible for providing humanitarian and developmental aid to children worldwide, says one in three children in Latin America have received "poor quality" distance learning.

On average, children in Latin America have lost nearly four times more days of schooling than in other parts of the world.

A severe lack of digital infrastructure across the continent has had a catastrophic impact on children in the poorest households, with many having no way to access remote classes, says Virginia Pérez, UNICEF's Bolivia chief.

57,000 children in Panama's remotest regions were left without any means of learning last year due to the pandemic

In Bolivia, around 60% of the country's population is indigenous. Just 28% of homes in the country have a computer and only 3% have basic access to the internet. More than 95% of UK households have internet access.

As a result, teachers have been forced to become increasingly creative in a bid to keep their students from falling behind.

"I've heard countless stories of teachers going out of the way to support their students. Some even travelling house-to-house, sometimes for miles, to offer them some semblance of learning," says Mrs Pérez.

Schooling in the rainforest

And It is not just teachers who are being pushed to get creative.

Governments in countries with limited internet access are bridging the digital divide with television and radio broadcasts in an attempt to reduce the number of children falling behind.

In Peru, more than 60% of the country is covered by the Amazon rainforest, and within it lies some of the world's most remote indigenous communities.

Indigenous students in Peru are using loudspeakers in their villages to listen to their teachers

When Covid-19 struck, thousands of children were cut-off from the outside world without the means to continue their education.

Authorities have since installed loudspeakers throughout the rainforest, strapping them to trees to broadcast lessons into the open air.

Children with disabilities throughout Latin America have also lost months of developmental progress without access to specialised learning and physical and mental therapy.

In Nicaragua, Dr Marieliz Rodriguez leads a programme that works with 787 children across the country under the age of six, all with disabilities.

'Inspiring examples'

When the pandemic hit, resources were redirected from face-to-face visits and replaced with acquiring mobile phones and computers for hundreds of the most vulnerable. This allowed rehabilitation sessions to continue remotely.

But with resources stretched, the programme has been forced to turn its attention to those considered most at-risk.

"We had to prioritize the most delicate and urgent cases, finding a way to continue with each family plan, despite the restrictions", says Dr Rodriquez.

In Nicaragua, parents Heyssel Téllez and Holsten Alemán feared their daughter, would lose months of progress

The UN says the longer schools remain closed the more devastating the consequences will be for children, not just academically, but also in developing social skills and their overall mental well-being.

But there is hope. UNICEF's executive director, Henrietta Fore, says the unprecedented global crisis has created a unique opportunity that could see the lives of millions of children transformed.

"Around the world we have seen inspiring examples of teachers, students, parents and governments adopting innovative new ways of learning. We must capitalise on this thirst for transformation.

"Through new approaches we can and will reach the hundreds of millions of children who have never had an education or are contending with poor-quality instruction. This will ultimately help us build strong, sustainable economies. This moment is now."

- Published13 March 2021

- Published12 March 2021