Would universities call parents in a mental health crisis?

- Published

"I got a knock on the door at 2.45 in the morning," says Lee Fryatt.

It was the police. His son Daniel, a 19-year-old student at Bath Spa University, had taken his own life.

"What you learn once you suffer a loss like suicide is that it's only other people who have experienced it who have got any comprehension of just how devastating it is.

"I've described it as grief turned up to the max, up to the point it's splitting your ears."

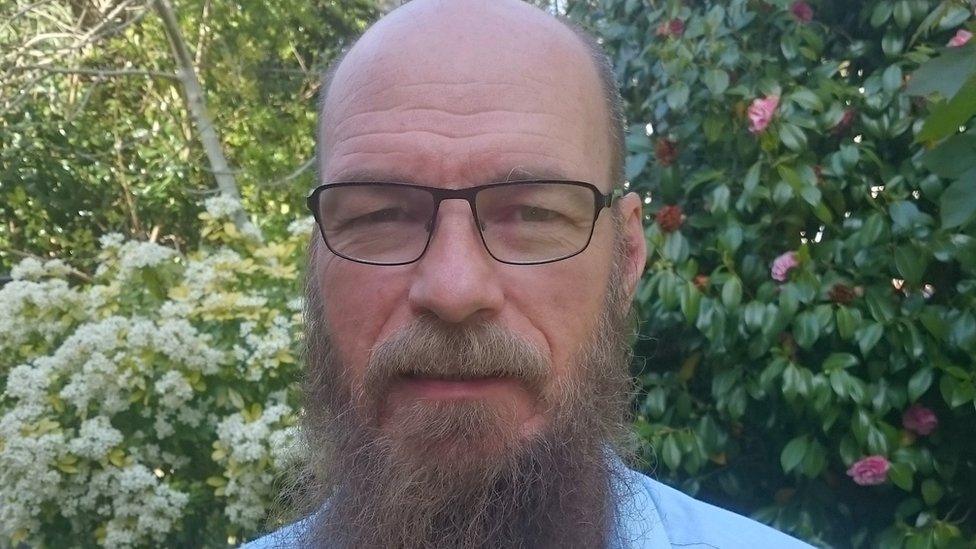

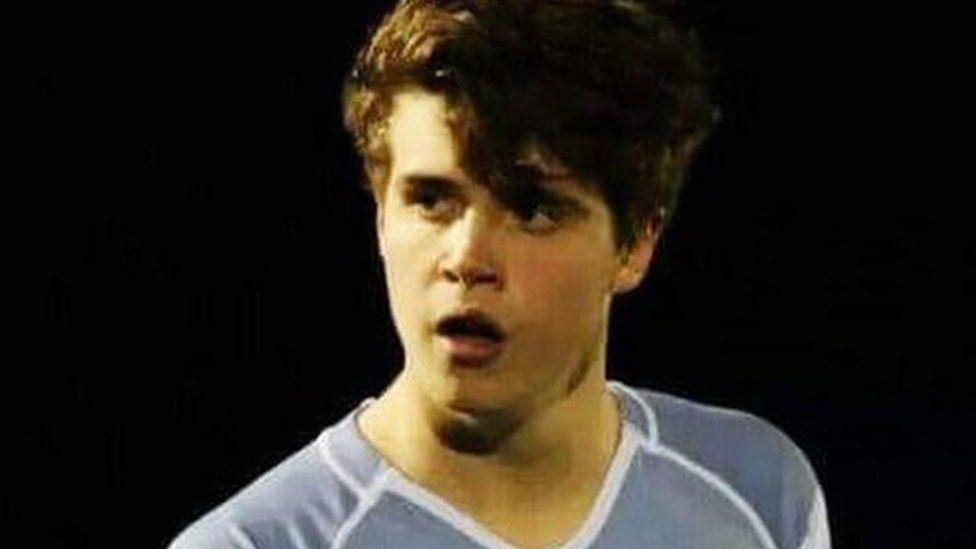

Former police officer Lee Fryatt wants universities to alert parents if there is a mental health crisis

Mr Fryatt, a former police officer living in Bournemouth, says what motivates him now is trying to prevent any more student suicides.

And he believes that if students are in a mental health crisis, universities should be much more willing to contact parents, or another trusted adult - and at least give them an opportunity to help.

"Like many parents, I was the last to know there was a problem, until it was too late.

"I genuinely believe that had I been told, Daniel would not have died that day."

Wrongly assumed

It might be a surprise and even a shock to some parents that they wouldn't necessarily be contacted if their son or daughter faced serious mental health problems at university.

"I absolutely assumed, quite wrongly, that if a concern about his wellbeing got flagged, I'd be told about it, I'd be alerted," said Mr Fryatt, particularly because his son had informed the university of previous mental health concerns.

It's an issue that has been raised repeatedly following student suicides - so often that you'd been forgiven for thinking it had already been dealt with.

Ceara Thacker's parents thought they should have been contacted about her problems

The parents of Ceara Thacker, a student who took her life at the University of Liverpool in 2018, were bewildered that no-one had alerted them about a previous suicide attempt three months before.

"For as long as I live, I will never understand why no-one at the university picked up the phone to us… and told us that our 19-year-old daughter was in hospital after taking an overdose," said her father, Iain, at the inquest.

Confidentiality

There have been repeated proposals for an "opt-in" system - where students could choose, or refuse, to allow universities to get in touch with a parent, or some other trusted adult, if there were serious concerns about their wellbeing.

It would be voluntary - because there might be strong personal reasons a student wouldn't want their parents involved - and it's important for universities to respect the confidentiality of adult students.

Iain with his daughter Ceara: "I will never understand why no-one at the university picked up the phone"

But it would be a back-up for students who wanted it, giving prior consent at the start of each year - and at the University of Bristol, where it has been introduced, more than 90% of students have opted in.

However 90% of the university sector isn't offering such a choice - or even 50% - and in fact, it's not at all clear what most universities are offering in such circumstances.

"Universities have been kicking this issue around now for years. They've been rowing around in circles on it and they've not moved forward. It's about time they did," says Mr Fryatt.

"My experience as a parent is there isn't any real transparency.

"Universities like to say things like 'mental health is everybody's business'. But if you're a parent, it seems like it's none of your business," he says.

In 2018, the year Mr Fryatt's son died, it seemed as though a more robust system for contacting parents was on its way.

The then universities minister Sam Gyimah spoke in support of an opt-in system for students to give permission for "parents or a trusted person" to be contacted, warning of students who might "fall between the cracks and feel overwhelmed in their new surroundings".

This was reinforced by the then education secretary Damian Hinds, who wrote to university leaders telling them to improve how they reached out to families, as the top line of a new mental health initiative.

Sam Gyimah, as universities minister, raised the issue of contacting parents three years ago

Many students backed the idea too. In 2019, a major annual survey from the Higher Education Policy Institute found a large majority of students agreed with the principle of universities contacting parents.

The institute's director, Nick Hillman, thinks universities were surprised by the strength of student support for involving families - and that this would have gathered more momentum if the pandemic had not intervened.

But how much has changed?

The issue of student suicides hasn't gone away. The most recent Office for National Statistics annual figures, from 2019, show 174 students in England and Wales had taken their lives.

But there doesn't seem to be any clear picture of how widely an opt-in system might have been adopted - or much clarity over what parents might expect to be told.

The universities watchdog in England, the Office for Students, says "individual universities are responsible for developing their own mental health policies" - and does not have any overview

Universities UK says it's already "good practice" to ask students if they want families involved - and guidance is to be produced on sharing information

The Department for Education says that all universities already have emergency contact details to use and "a few universities are piloting an additional opt-in system"

It's not exactly a new issue, but more of a loop tape.

A Universities UK report in 2002 on student suicides warned: "Many parents have, not unnaturally, expressed significant concern about the reluctance of higher education institutions to pass on to them information about sons or daughters whose behaviour or mental state is causing them particular concern."

But it said universities were "rightly reluctant to disclose any personal information without adult students' express permission".

And later this month, the inquest will be held into the death of University of Warwick student, Will Bargate, whose father has said: "I am personally convinced, had they contacted us, Will would still be alive today."

Frustrated at the lack of transparency, Mr Fryatt and a group of bereaved parents have carried out their own Freedom of Information request.

They found only about 32 universities or individual Oxbridge colleges, out of 149 responses, have a system for students to opt into such a scheme.

Among the rest, they found a confusing mix of approaches, and Mr Fryatt warns families to look carefully at what they might or might not be told.

There were universities which already had their own system for contacting people in an emergency - and so didn't need to move to a more standardised approach, or arrange prior consent.

Data privacy

There were data protection concerns too. But the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) has downplayed this.

"In an emergency, such as where there is a risk to human life, organisations should go ahead and share data as is necessary and proportionate," said an ICO spokeswoman.

There was also opposition on the principle of sharing information - that it was a breach of students' confidentiality, and that getting parents involved could make matters worse.

This is an understandable objection. For instance, there could be issues about sexuality or a student's personal life, where involving families could be a terrible mistake and exacerbate problems.

Young people might be trying to escape their families, rather than want them interfering.

Sara Khan, National Union of Students vice-president, says: "We cannot know when contacting parents and families without consent could put a student in danger.

"Removing this confidentiality would make students less likely to come forward and seek support."

Mr Fryatt says, after 30 years in the police, he knows well that many young people might have dysfunctional relationships with their families and it might not help to involve their parents.

But he argues that the default position - that students are adults and families should not be involved - is the wrong way round.

Especially for those students who arrive at university with a history of mental health vulnerabilities, he thinks parents, or other relatives or friends, might be able to provide critically-important information and support in an emergency.

"We're not suggesting for one minute that every time a student skips a lesson or dips some exam grades that parents are told," says Mr Fryatt.

"What we're talking about here is when there are genuine safeguarding concerns about somebody's physical or mental wellbeing."

Imperial College London decided this year to adopt such an opt-in system for notifying parents or another trusted person.

Hannah Bannister, the university's director of student services, says it will provide "clarity" about what would happen in a mental health emergency - a question that gets raised on open days.

On the issue of student confidentiality, she says it's important that students are in "control" - they can choose not to give permission and can change that at any point.

But she sees a real advantage in having these discussions before there is a crisis, rather than in an emergency when students might not want to respond or make decisions.

Even as the contact scheme is being rolled out, it's already been used twice over concerns about students.

James Murray speaking in 2019 about involving parents when students are in serious need of support

The University of Bristol's opt-in scheme - and its "emergency response protocol" - was used 36 times in its first year.

James Murray, whose son Ben took his life in 2018 while a student at the university, thinks the question needs to go back a step further.

It's not just whether parents would be contacted, but whether universities would even be able to spot when a student was in serious difficulty.

The debate about information sharing shouldn't only be about what families are told, he says, but about how information is shared between different parts of a student's life - whether academic staff, welfare services or their accommodation provider.

Ben Murray's parents were not aware of the extent of his problems at university

Mr Murray says that in the case of his son, many individual staff had concerns over several months, but these warning signs were never joined up.

He says he got an app to make a "network diagram" of the missed connections. "There were 30 different members of staff, halls, school faculty involved - 130 different email contact points," he says.

And no-one told the parents that the 19-year-old student's problems had escalated to the point he was having to leave.

What's missing in the debate, says Mr Murray, is a "sense of urgency" and a "lack of oversight" in taking mental health seriously enough.

"It might seem radical," he says, but why shouldn't the Office for Students threaten to deregister universities over mental health failings, as well as academic problems?

None of these are simple issues - and every story of someone's loss is different. And neither of these bereaved parents think that contacting a family is always going to be the right approach.

But should teenagers, used to support from parents and teachers at school, be expected to suddenly become independent adults when they unpack their bags at university?

It raises questions about what exactly is the duty of care of a university? As Mr Fryatt says, the Prevent regulations mean a university has to make sure a student isn't an extremist. But what reporting duties are in place about them being extremely unwell?

Mr Fryatt, speaking of his own experience, says "I know in my heart that if the university had rung and told me what was happening" that he would have recognised the warning signs of a "massive risk factor".

He could have had the chance to get there.

"But none of that happened," he says.

If you or someone you know has been affected by these issues, support is available at the BBC Action Line including the Samaritans, external

- Published9 February 2020

- Published13 June 2019