Election 2015: Why do we have election manifestos?

- Published

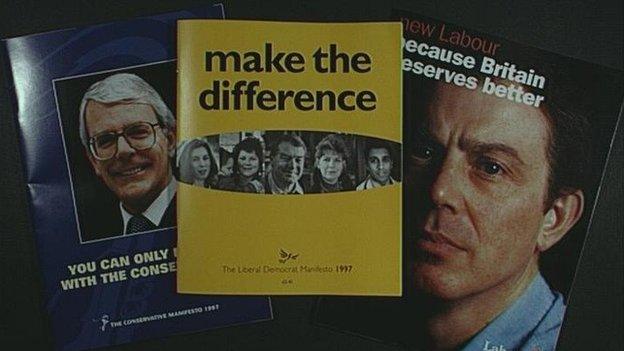

As Westminster's largest parties launch their general election manifestos, here is a guide to the significance and history of these much-scrutinised documents.

Election manifestos are written with single party government in mind. What is their place in elections where no single party wins a majority?

At the 2010 general election all the contending parties fought campaigns based on published manifestos that set out for electors the policies they intended to pursue in government.

But every party lost that election. The hung Parliament that resulted produced the first peacetime coalition government in the United Kingdom for 80 years, and one committed to a programme based on a coalition agreement.

The Lib Dem cabinet minister, Vince Cable, summarised the difference in 2010 when challenged about breaking the party's manifesto commitment to abolish tuition fees.

"We didn't break a promise. We made a commitment in our manifesto, and we didn't win the election. We then entered into a coalition agreement, and it's the coalition agreement that is binding upon us and which I'm trying to honour."

Moral contract

But it was the Lib Dem manifesto that helped attract 6.8 million votes to the party in May 2010, not a coalition agreement that none of them had heard of, let alone seen.

How could they? It was the result of a post-election deal. Such arrangements are quite common in many countries, especially those where proportional voting systems make single party government infrequent. But they lie outside the experience of voters in first-past-the-post Westminster elections.

But why is there all this fuss about manifesto commitments? The late Labour politician Peter Shore once described manifestos as "a party's contract with the electorate".

He did not mean a legal contract but rather a moral contract between MPs and voters based upon the programme the MPs committed themselves to implement if elected to government.

And the potency of the mandate given to a government's election manifesto was recognised by the Salisbury convention.

Party manifestos are scrutinised carefully by the electorate

During the post-war Labour government, the Conservative leader in the House of Lords, the Marquess of Salisbury, formulated the doctrine that Conservative peers could use their inbuilt majority to amend legislation that the electorate had clearly voted for, but not defeat it.

And manifestos, certainly in the post-war period, have held a special status among civil servants. Not only are these documents closely studied within every government department, but the commitments contained within them carry a distinct authority as far as the civil service is concerned. But where did all this come from?

In 1834, whilst on holiday in Rome, Sir Robert Peel was invited by King William IV to form a minority government to replace the Whig administration of Lord Melbourne.

'Frank exposition'

The law at that time required him to resign his seat of Tamworth and seek re-election as a Minister of the Crown.

He published a manifesto in the resulting by-election, stating: "I feel it incumbent on me to enter into a declaration of my views of public policy, as full and unreserved as I can make it".

One reason for publishing it was his opinion that voters required "that frank exposition of general principles and views... which it ought not to be the inclination, and cannot be the interest of a minister of this country to withhold".

Peel was robust about the terms on which he would accept re-election and government office: "I will not accept power on the condition of declaring myself an apostate from the principles on which I have heretofore acted."

His manifesto reflected the political issues of the day and the restricted electorate whose votes he was seeking - currency, criminal law, the Reform Bill, municipal corporations, Church reform.

At the end of this 2,300 word Tamworth Manifesto, Peel felt able to declare that he had said enough "with respect to general principles and their practical application to public measures, to indicate the spirit in which the King's government is prepared to act".

Peel set out the essence of a party manifesto that we can easily recognise nearly 200 years later: a full and public declaration of policy that a party aspiring to government offers for the verdict of the electorate.

Party manifestos have certainly developed since 1834 and not least in respect of the changing priorities addressed in them.

In 1900, the Conservative election manifesto amounted to 887 words and contained (at a stretch) four pledges. The party's 2010 manifesto comprised 27,835 words and contained 620 pledges.

But the Peel Principle remained unchallenged throughout this period: namely, voters are entitled to know what politicians intend to do in government before they cast their ballots.