Election 2015: What will happen after 8 May?

- Published

Ed Miliband said his meeting with Russell Brand had made the general election campaign "more interesting"

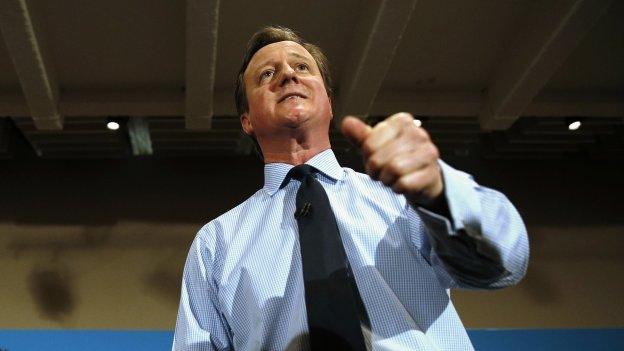

Mr Cameron is finally pumped up and uses a mild swear-word. Ed Miliband visits the celebrity who is famous for not believing in voting. If you detect an air of desperation it is not surprising.

We await a tsunami. After an almost becalmed campaign, the election result is likely to wreak havoc on not just the parties, but perhaps the familiar structures of British politics, carrying away old assumptions - a reflection not just of the changing weather in the UK but change to the global political climate.

While the politicians' irritation at all the speculation about what happens after 8 May is understandable, that is the pivot - the story - that matters. The campaign will be quickly forgotten, while the impact of the result will last for five years and beyond.

All right, all right, that caveat. The opinion polls are snapshots, not predictions. They "suggest", they don't "show". But I haven't seen a single one that points towards anything other than a hung parliament. I think it is a real possibility that many people will dislike that potential outcome and vote accordingly. That could stop the "suggestions" becoming a reality.

But if we do end up with no one party winning an overall majority, then drama and trauma will follow. It will be much more difficult than 2010. Once felt like an accident. Twice would be a trend.

BBC News Timeliner: Better together?

In 2010 UK voters returned a hung parliament, resulting in the first coalition government since World War Two.

Revisit the 2010 general election with the BBC News Timeliner, external

'The chop'

We will hear a lot about legitimacy. In a hung parliament the authority of the prime minister, whoever that is, will be in question.

David Cameron is finally pumped up

If David Cameron pulls off a repeat performance he will have failed for a second time to completely beat an opponent portrayed by many as uninspiring. Rupert Murdoch has already tweeted, external that would mean "the chop". PM Miliband would be in a slightly less precarious position but there would be much muttering that another leader could have done better.

If the prime minister is from the party that did not win the most MPs there will be different questions about his legitimacy. This may fly in the face of both arithmetic and an understanding of how parliamentary democracy works but that won't stop the critics.

Perhaps they have just seized on the wrong word - legitimacy is not the same as mandate. One columnist says it's about "smell"., external He's right. Whoever wins, someone will say it stinks.

New opposition leader

Which party leaders will be left standing after the election?

The other parties' fates will depend on their performance, of course, and for the Greens and UKIP any gains would be good.

The Liberal Democrats could lose a substantial number of seats and still be a critical part of a government but that too would raise questions of legitimacy and mandate. Nick Clegg might be in a precarious position, and there will be a deep debate about what the party, at heart, is for.

The leader of the main party who becomes the leader of the opposition surely won't be in the job for very long. It's possible to think of circumstances where their resignation wouldn't happen, but impossible to imagine one where it wouldn't be expected.

In either party the ensuing leadership election would be a profound debate about direction, purpose and role, as well as character. The Conservatives would tear the sticking plaster off the wound that never heals - their debate over Europe, the argument between nationalism and laissez-faire economics. At least they have a hero waiting in the wings, albeit a floppy-haired and controversial one.

Boris Johnson - future Conservative leader?

Labour, with no such charismatic character waiting offstage, would scratch its own old sores, reviving old debates about Blair and brothers, blue Labour and red Labour.

If the SNP sweeps Scotland, the damage to Labour's sense of self will be enormous. We've speculated endlessly about the damage it would do to their hopes of forming a government.

What we haven't seen is the shock to their system. When someone is gravely ill, not expected to linger more than a few days, all their friends and relatives are intellectually aware of what is going to happen. But it is not the same as the death itself - that is when the tears flow, and the grief and the mourning, and the enormity of loss strike home.

So with Scotland. In or out of power, such a result would force wider reflections on why Labour didn't win, say Kent, or more seats in the south.

Fractured voter coalitions

In or out of power, the Conservatives would have the same debate about why they haven't had a majority for 23 years, and what happened to the people who gave Thatcher and Major their victories.

This points to the heart of what is happening to politics in the UK.

If we do see a new coalition - formal, informal or unacknowledged - it will be because the real coalitions in British politics have fractured apart: the coalition of voters who supported the massive parties of left and right. They fed the appetite of these behemoths, kept alive these huge beasts, creations of another century.

What if nobody wins the election?

If no single party has an overall majority, there are three main options for the sort of government that could be formed:

a formal coalition, made up of two or more parties which usually includes ministers from more than one party

an informal agreement, in which smaller parties would support a government on major votes in return for some concessions

or a single-party minority government, where the biggest party goes it alone and tries to survive vote-by-vote supported by a series of ad hoc arrangements

Perhaps this is over-dramatic. Perhaps a charismatic Labour leader with clever policies can rebuild an alliance across uncertain geographies of disillusioned former industrial workers, the aspirant working and middle class, and a discontented Scotland. Perhaps their Tory equivalent can find the language and the ideas to pull back the working-class Tories, the middle-class public sector workers, and do it outside England.

But it would be hard.

The trick of keeping together people divided by geographical variations and no longer firmly bound by ideology and class may need a political genius.

For there is an argument that the fatal disconnect is not with politicians and their parties but with politics itself.

These days you can order a fridge or washing machine with the click of a mouse, but to vote you have to trudge to the nearest local school and make a mark with a stubby pencil. Recently politics has caught up with the 19th Century - you can also now use the Royal Mail.

This is not merely a trivial point about online voting. The thing about the white goods is that you can send them back, probably if you change your mind, certainly if they stop working to your satisfaction. And if you have the cash no-one will stop you chucking them out and buying a new one.

But political parties offer a messy bundle of promises on subjects as far apart as tax, war and sex, no longer tightly bound together by a coherent world view or ideology. They expect you to trust them to steer the right course past pitfalls we can see looming and obstacles we can't, when trust is in short supply.

It is beyond the boundaries of my job to offer a solution, and it is a relief that I am so muzzled, otherwise you would discover that I have only questions, not answers.

But 8 May is not the end of the argument about the purpose and worth of politics, only the beginning.