What is Marx's Das Kapital?

- Published

Karl Marx published the first volume of Das Kapital in 1867

Labour's shadow chancellor John McDonnell has said there is much to learn from reading Das Kapital. What is it?

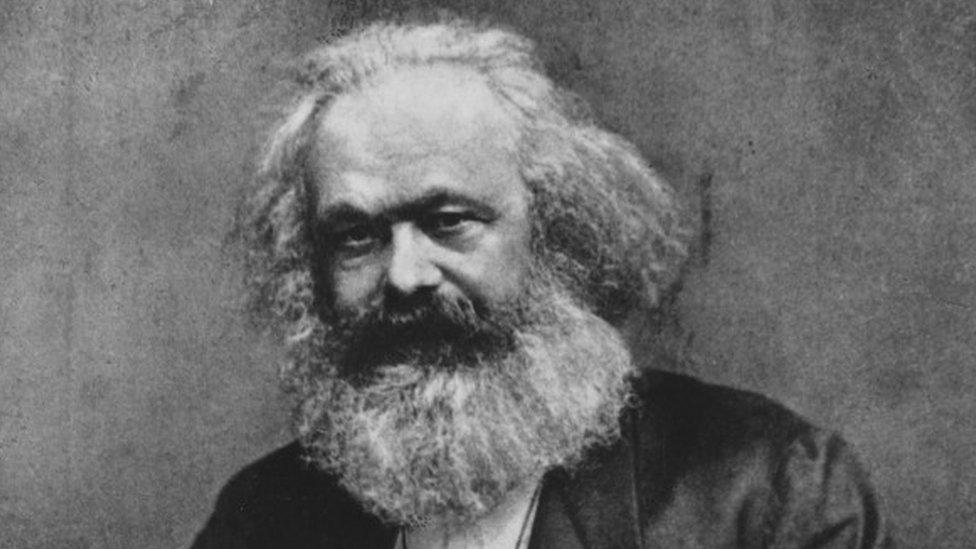

Written in the middle of the 19th Century by German philosopher and economist Karl Marx, Das Kapital is essentially a description of how the capitalist system works and how, Marx claims, it will destroy itself.

Marx had already set out his ideas on class struggle - how the workers of the world would seize power from the ruling elites - in the Communist Manifesto and other writings.

Das Kapital is an attempt to give these ideas a grounding in verifiable fact and scientific analysis.

It is not an easy read. The product of 30 years of work, and Marx's study of the condition of workers in English factories at the height of the industrial revolution, it is part history, part economics and part sociology.

As Marx's biographer Francis Wheen has pointed out, external, it reads at times like a Gothic novel "whose heroes are enslaved and consumed by the monster they created".

In simple terms, Marx argues that an economic system based on private profit is inherently unstable.

Workers are exploited by factory owners and don't own the products of their labour, making them little better than machines.

John McDonnell is a keen student of Marx's most significant work

The factory owners and other capitalists hold all the power because they control the means of production, allowing them to amass vast fortunes while the workers fall deeper into poverty.

This is an unsustainable way to organise society and it will eventually collapse under the weight of its own contradictions, Marx argues.

He is not clear about when this will happen, only that it is inevitable. Neither does he explicitly spell out what the communist society that will replace capitalism will look like, only that it will free workers from their servitude (he did not complete work on his theories before his death in 1883 so perhaps he ran out of time).

Marx published the first volume of Das Kapital in 1867, by which time he had settled in London with his family, and was being financially supported by Friedrich Engels, the rich son of a cotton mill owner.

He continued to refine the ideas set out in the first volume for the rest of his life, although the next two volumes would not appear in print until after his death.

The ideas contained in Das Kapital would go on to inspire revolutions in Russia, China and many other countries around the world in the 20th Century, as ruling elites were overthrown and private property seized on behalf of the workers.

Marx predicted the collapse of capitalism

They would also exert a powerful influence over many in the Labour Party and the trade union movement, even if they did not always share his vision of a global workers' revolution.

Marxism became a way of interpreting the world - the simple idea at its core that history was a battle between opposing social classes could be applied to everything from the study of literature and film to the education system.

It also became a byword for totalitarianism - as one-party states and dictators proclaimed Marxism as their guiding philosophy.

Some argued that this was a perversion of Marx's ideas as set out in Das Kapital, and that the Soviet Union, for many the ultimate example of a Marxist state, was really just a form of state capitalism, where the factory owners had been replaced by government bureaucrats.

But the Soviet Union's collapse in the early 1990s dealt a major blow to the credibility of Marxist theory and it went out of fashion on university campuses and in mainstream left-wing political parties that aspired to gain power in the West, such as the Labour Party.

It underwent something of a revival in the wake of the 2008 global financial crash, however, which some saw as a classic example of capitalism in crisis, just as Marx had predicted.

- Published7 May 2017