How does draft manifesto compare with Labour's 1983 one?

- Published

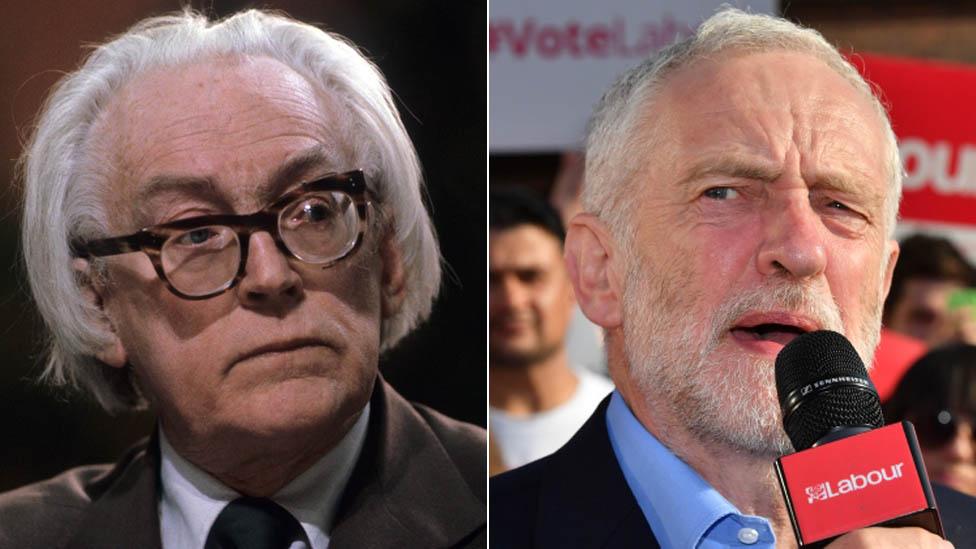

Michael Foot and Jeremy Corbyn - Labour leaders from different eras

Labour's draft general election manifesto has been compared by some with the party's 1983 manifesto - how do the two documents measure up?

The 1983 manifesto was written at a time of economic turmoil, mass unemployment and Cold War tensions and is arguably more ambitious in its scope. It is certainly framed in more forceful language.

"Within days of taking office, Labour will begin to implement an emergency programme of action, to bring about a complete change of direction for Britain," it says.

"Our priority will be to create jobs and give a new urgency to the struggle for peace. In many cases we will be able to act immediately."

They are very different documents in many ways, written to reflect the concerns of their respective times.

Jeremy Corbyn's draft manifesto uses a more measured tone, talking about "delivering a fairer, more prosperous society for the many, not just the few".

There is no mention of socialism, in contrast to the nine mentions it gets in 1983.

But at the 2017 manifesto's heart is the same commitment to using government intervention and public money to boost industrial development and create jobs.

In 1983, Labour leader Michael Foot had a five year "emergency programme" to rebuild industry and end mass unemployment. In 2017, Jeremy Corbyn proposes a "a ten-year national investment plan to upgrade Britain's economy".

Labour propose massive public investment, withdrawal from the EEC and nuclear disarmament in their manifesto for the 1983 general election

Tax and spending

Both manifestos propose higher taxes on the rich and a crack down on tax avoidance.

In 1983, Labour said: "We shall reform taxation so that the rich pay their full share and the tax burden on the lower paid is reduced."

In 2017, Labour says "only the highest 5% of earners will be asked to contribute more in tax to help fund our public services".

The 1983 manifesto goes further, proposing "a new annual tax on net personal wealth" to "ensure that the richest 100,000 of the population make a fair and proper contribution to tax revenue".

Industrial strategy

Both manifestos include plans for a National Investment Bank to boost industrial development and support research and development.

The 2017 version would allow the government to use public money to support long-term, higher-risk investment that the bank's are reluctant to touch.

The 1983 version of the National Investment Bank is more interventionist.

It proposes drawing up development plans with "all leading companies - national and multinational, public and private". Like the 2017 plan, it would provide access to credit, but a Labour government would have the power to "invest in individual companies, to purchase them outright or to assume temporary control".

The 1983 manifesto also includes a commitment to reintroducing exchange controls, scrapped by the Conservatives in 1979, to "counter currency speculation" and stop capital "flowing overseas".

Nuclear weapons

In 1983, Labour was committed to scrapping Britain's nuclear weapons, saying "we are the only party that offers a non-nuclear defence policy."

In 2017, Labour says it supports "the renewal of the Trident submarine system".

But, in a possible nod to Jeremy Corbyn's longstanding opposition to nuclear weapons, it adds "any prime minister should be extremely cautious about ordering the use of weapons of mass destruction which would result in the indiscriminate killing of millions of innocent civilians".

Both manifestos stress the need for Britain to work for nuclear disarmament through international bodies.

Europe

Although the 2017 draft manifesto backs Britain's exit from the EU, following last year's referendum result, it is less Eurosceptic in tone than the 1983 document.

It praises the EU for protecting workers' rights and the environment and vows to fight to keep them in Brexit negotiations.

The 1983 manifesto says European Economic Community, as the EU was then known, "was never devised to suit us, and our experience as a member of it has made it more difficult for us to deal with our economic and industrial problems".

Labour promised to begin withdrawal from the EEC without a referendum if it won power.

Nationalisation

The 1983 manifesto pledges to renationalise the industries privatised by the Thatcher government.

The 2017 manifesto includes plans to renationalise the Royal Mail and the railways - which were still state-owned in 1983 - and part-nationalise the energy industry. Labour would also "take control" of the National Grid if it won power.

The unions

The trade unions play a more central role in Labour's 1983 plans for the economy, reflecting the greater power they had at that time.

The 2017 manifesto includes plans to restore some of that power by repealing the 2016 Trade Union Act and bringing back collective pay bargaining to some sectors. A Ministry of Labour would be introduced to oversee increased unionisation across the workforce.

Housing

Both manifestos include plans to build more council houses and offer more protections to private renters.

They also include plans to help more people buy their own homes and crack down on leasehold abuses. Jeremy Corbyn would also halt the sale of social housing, in an echo of the 1983 manifesto's pledge to end council house sales.

Price controls

Labour's 2017 manifesto includes plans to cap energy prices.

In 1983, the party would have gone much further.

It proposed "a new Price Commission to investigate companies, monitor price increases and order price freezes and reductions. These controls will be closely linked to our industrial planning, through agreed development plans with the leading, price-setting firms".

It would "take full account of these measures in the national economic assessment, to be agreed each year with the trade unions".

Health

Increased spending on the NHS is a key priority in both the 1983 and the 2017 manifestos.

In 1983, Labour pledged to "increase health service expenditure by 3% per annum in real terms".

In 2017, Labour is promising to spend an extra £6bn to be paid for tax increases on higher earners.

Labour's 2017 manifesto vows to "reverse" privatisation of the NHS. In 1983, the party promised to curb the expansion of private health care and "take into the NHS those parts of the profit-making private sector which can be put to good use".

"We will not allow the development of a two-tier health service, where the rich can jump the queue," the 1983 manifesto adds.

Education

Both manifestos include a commitment to cut class sizes to below 30, although the 1983 manifesto pledges this for all schools, while the 2017 version says it will initially be for "all 5, 6, and 7 year olds", with the rest to follow "as resources allow".

Jeremy Corbyn is also pledging to introduce free school meals for all primary school children, paid for by removing the VAT exemption on private school fees.

The 1983 manifesto includes plans to charge VAT on private school fees and promises to "re-establish the school meals and milk services, cut back by the Tories".

It describes private schools as a "major obstacle to a free and fair education system" and promises to end their charitable status and "integrate" them into the local authority sector "where necessary".

It also rejects the "Tory proposals for student loans," a policy echoed in Jeremy Corbyn's pledge to scrap tuition fees and bring back maintenance grants for low-income students.

The 1983 manifesto also pledges to scrap corporal punishment - the beating of children with canes or straps - in schools. The Conservatives outlawed this in state schools three years later.

Immigration

Net migration to the UK - the difference between the numbers coming to live in the country and those leaving - was 17,000 in 1983 - a fraction of what it is today.

In 1983, Labour said it accepted the need for immigration controls but vowed to scrap Conservative laws restricting the rights of Commonwealth citizens to remain in the UK and replace them with "a citizenship law that does not discriminate against either women or black and Asian Britons".

In 2017, Labour says it would scrap the Conservative target of reducing net migration to the "tens of thousands" and instead make a positive case for "controlled" migration to boost the economy.

It would bring in laws to stop companies undercutting wages with migrant workers or recruiting workers solely from abroad.

And finally.. Broadband

The internet may have been a distant dream in 1983, but then, just as now, broadband was a major preoccupation for Labour politicians, it seems.

The 1983 manifesto envisages a "national, broadband network" to carry a "wide range of new telecommunications services" and "greater variety in the provision of television".

But, it adds, this important new system must be "under firm public control", with the job of building it handed exclusively to "publicly-owned British Telecommunications".

Thirty four years later, the Labour manifesto includes a whole raft of broadband promises, including "universal superfast broadband availability by 2022", although there are no plans to renationalise BT to deliver it.

- Published11 May 2017