Who is Paul Nuttall? A profile of the ex-UKIP leader

- Published

Paul Nuttall has stepped down as UK Independence Party leader after a disappointing performance in the general election. Since his appointment as leader in November he had had a torrid time.

The anti-EU party is arguably the most successful political movement of the past 20 years - there would have been no EU referendum and, therefore, no Brexit without it.

But it now faces the difficult task of finding a role for itself, having achieved what it was set up to do. Does UKIP have a second act? Or will it return to the political fringes or even break itself apart in another bout of infighting?

Mr Nuttall had said Brexit was only a "job half done" and UKIP MPs were needed to "see this through to the end".

He has accused Theresa May of "backsliding" on immigration and says a "whopping Conservative majority" would "put Brexit in peril".

But he also agreed not to stand UKIP candidates against Conservative candidates he regarded as "true Brexiteers".

He freely admitted that this would be a tough general election for his party, a point driven home by disastrous local election results which saw the party lose all 146 of the council seats it won four years ago, as its voters switched to the Tories. It was scant consolation that they picked up one councillor in Lancashire.

But he had maintained that UKIP was in with a chance of winning seats at the general election, if it could target its resources properly. The party stood in just over half of the UK's constituencies, a big reduction on 2015, when it won four million votes. It did not win any seats.

Paul Nuttall enjoys a drink with his predecessor

Mr Nuttall was not a household name like his predecessor Nigel Farage, but he was cut from the same plain-speaking cloth.

The two men share a delight in challenging what they see as politically-correct taboos and projecting a "man of the people" image with a pint in hand, although Mr Nuttall favours Guinness over the "warm beer" quaffed by Mr Farage.

In the past, he has called for a war against "cultural Marxists", who "have changed the way we speak and the way we think", adding: "They've made the downright nonsensical acceptable and common sense unacceptable or politically incorrect."

A global warming sceptic, in 2010, he said UKIP would ban former US Vice-President Al Gore's climate change film An Inconvenient Truth from schools, calling it a "blatant piece of propaganda".

He also said he would back a referendum on capital punishment, "if enough thought that was justified", for the killers of children.

And he has been just as outspoken as Mr Farage on the subject of immigration, claiming in a speech to the European Parliament, that the EU's migration policies were enabling a "freedom of movement of jihad".

Who is Paul Nuttall?

Date of birth: 30 November 1976 (age 40)

Education: State-educated at Savio High School, Bootle, Hugh Baird college, Edge Hill college and Liverpool Hope University

Family: Married wife Linda in 2008 but the relationship ended in divorce in 2011. One child.

Hobbies: Supports Liverpool football club. Was a member of Tranmere Rovers' youth squad in the early 1990s

A former history lecturer, Paul Nuttall became UKIP leader two days short of his 40th birthday. He was born in Bootle, Merseyside, on 30 November 1976, part of a Catholic family, attending local state schools.

After leaving school he studied sport science at North Lincolnshire College, history at Edge Hill College and trained to be a teacher at the University of Central Lancashire.

He worked part-time as a classroom assistant at St Winefride's Primary School, Bootle, while he took a master's degree in history from Liverpool Hope University. Mr Nuttall is said to specialise in the Edwardian era. After graduating he lectured at Liverpool Hope University from 2004 to 2006.

But he was already interested in politics. In 2002, aged 25, he ran for the Conservatives in a council election in Bootle. He told the Daily Post: "I was brought up in a staunch Labour community and never really thought about voting any other way.

"I left home for a few years and coming back to Bootle made me fully appreciate the levels of decay and decline. Now I just want to give people a reasonable alternative."

Defeat in the Stoke-on-Trent by-election was a setback

In 2004, Mr Nuttall joined UKIP, then a minor party in terms of its share of the vote in Westminster elections.

He became an MEP - the youngest of the party's representatives in Brussels and Strasbourg - for North West England in 2009 and, a firm ally of Mr Farage, he served as his deputy from 2010 until this September.

When Mr Farage quit the leadership following last year's Brexit referendum, Mr Nuttall - immediately considered one of the favourites to succeed him - decided not to run, saying he too wanted his "life back".

"I have been at the forefront of the campaign to leave the European Union for a decade now," he said, "and I believe I can step aside with my objective achieved and my head held high."

But Mr Farage's replacement as leader, Diane James, quit after just 18 days in the job and the vacancy reopening led Mr Nuttall to put himself forward. As several candidates pulled out he came, with the backing of much of UKIP's establishment, to be seen as the favourite.

Mr Nuttall won with 62% of the vote and was immediately pitched into a media storm when two of his MEPs got into a fight, which left one of them, Steven Woolfe, in hospital. Mr Woolfe, a one time leadership contender, has since left the party.

Mr Nuttall described the "altercation" as "probably in the long-run the best thing that happened to the party".

"Everyone woke up and smelt the coffee and understood that this was now an existential crisis and it was my duty to step in, stand in this election, win it and bring the party together, and that's what I intend to do."

With his Scouse accent and working class background, Paul Nuttall was meant to reach the parts of Britain that Home Counties-bred, public school boy Farage could not.

Speaking to the Sunday Telegraph after becoming leader in November, Mr Nuttall said: "We have this fantastic opportunity, which we've never had before to this extent, to move into Labour working-class communities and mop up votes.

"I think in some of these communities we can replace the Labour Party in the next five years and become the patriotic party of the working people."

He flunked the first test of these ambitions in March, when he failed to take Stoke-on-Trent from Labour in a by-election, in an area that voted strongly for Brexit, although he did succeed in shrinking Labour's majority.

His campaign was not a smooth one, with questions raised about where he was living - and past claims on his website that he had lost a close friend in the Hillsborough disaster.

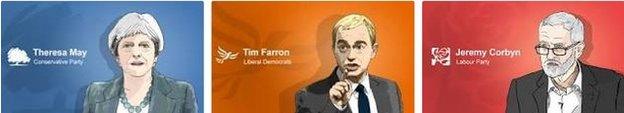

Leaders' profiles

There was more bad news for the party when its only MP Douglas Carswell quit shortly before Theresa May called a snap general election, saying its work was done, although few in the party, including Mr Nuttall, seemed sorry to see him go.

Mr Nuttall courted controversy by announcing at the start of the election campaign that UKIP would ban full face veils and sharia courts. He denied he was re-inventing UKIP as an "anti-Islam party".

"Integration is actually getting worse in Britain at the moment, not better. This will help," he told the BBC's Andrew Marr show.

"This isn't an attack specifically on Muslims, it's all about integration. It cannot be right we have courts or councils in this country where the words of a woman are only worth half that of a man. That has no place in a liberal, democratic functioning western democracy."

UKIP leaders have struggled in the past to convince voters that they have a coherent set of policies beyond leaving the EU and curbing immigration - former leader Lord Pearson admitted in 2010 that he had not read all of that year's manifesto and Nigel Farage later declared its contents "drivel".

But it did not matter so much when the party was leading the charge for an EU referendum.

But now Mr Nuttall has presided over a major slump in UKIP's vote at the general election. He departs with the party's vote share having dropped to 1.8%, leaving a major task for whoever his permanent successor turns out to be.