Election Lexicon: The lost significance behind this week’s buzzwords

- Published

Monsieur Zen (self-proclaimed)

Every general election throws up buzzwords and curiosities which help to define the tenor of the campaign. So what words have caught the ear in week one of the 2017 contest?

Battle bus

Conservative candidates and officials learned this week that they would not face charges for breaches of expenses rules over use of a "battle bus".

But what precisely is a battle bus?

The exterior is grimly familiar: a shiny patina of party logos and rudimentary slogans.

But when the battle bus was first used in the UK, its insides were to change politics irrevocably.

Rather than have their spouses drive them to campaigning events, politicians of the late 1970s could travel in a six-wheeled office with state-of-the-art equipment - and not just the air conditioning.

Here's Margaret Thatcher with some unimaginably futuristic communications technology:

The perks were even greater for political journalists, who no longer had to drive in clumsy convoy with the party leaders or search for telephone booths to file their reports.

They too could stay connected - and as the kit advanced to the word processors and "disc fax" machines of the 1980s, speech-writing, campaigning and reporting all lived and breathed the same fervid, sometimes foetid, air.

Election live: Rolling updates

The words "battle bus", then, are not just a straightforward term for a mode of transport; they describe an accelerated kind of politics, where candidates are always on-grid and where the media are part of the machine. Everywhere is now a battle bus.

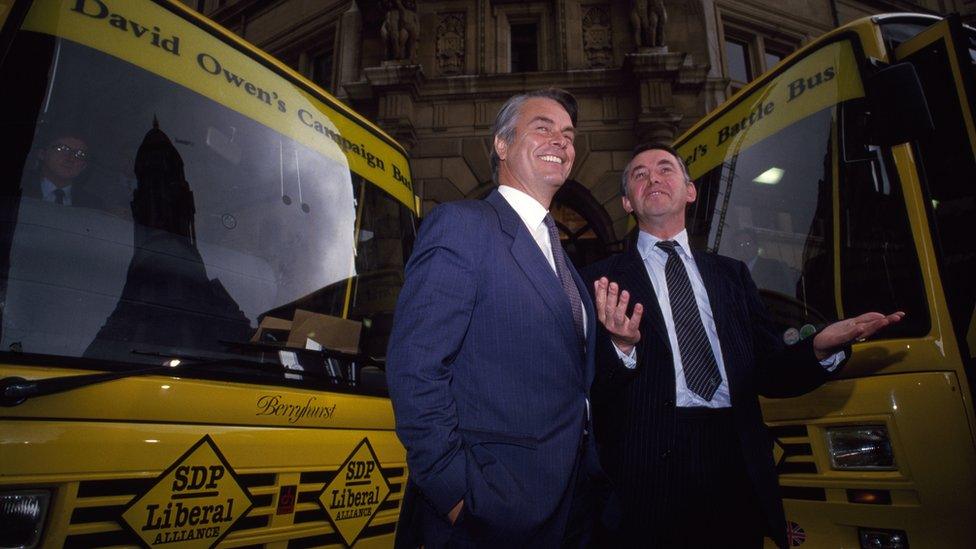

And the repercussions were keenly felt by the people most associated with the golden age of the battle bus - Davids Owen and Steel of the the Liberal/SDP Alliance - not least because each had his own bus, replete with period personalised windscreens.

David Owen and David Steel with their respective battle buses

Double the liberal fun - except that the onboard journalists rapidly realised that they could play the leaders off against each other in transit, getting a statement from one and getting the other to ridicule it before realising where it had come from.

Perhaps that's why today's Lib Dems have switched their affection to another futuristic conveyance...

Hovercraft

Lib Dem leader Tim Farron campaigned in a hovercraft this week in Burnham-on-Sea, apparently undaunted by the experiences of Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe, who campaigned for the second of 1974's pair of elections using the same vehicle.

Tim Farron trying a different mode of transport on the campaign trail

Reasoning that voters could be found on beaches, Thorpe decided to surprise them by arriving from the sea in a campaign that ended only when colossal waves near Sidmouth nearly drowned the oilskinned candidate and left his hovercraft in pieces on the shingle.

At that time, there was one crucial difference about the word hovercraft. It tended to have a capital "H", as it was a proprietary term like Hoover or Portaloo.

The preferred generic phrase was "air-cushion vehicle"; others used "sea-saucer" until the lower-case "hovercraft" took over.

Other terms you may not have realised are proprietary include Jacuzzi, Memory Stick, Quorn, Autocue and Rawlplug.

Draft manifesto

A draft simply means a drawing: a preliminary sketch, loose on the details, while manifesto is supposed to mean "clear to the eye" (as in, manifest). A draft manifesto in its very nature, then, is asking for trouble.

Labour's draft manifesto has been hastily converted to the real thing this week after a leak, which the Conservatives promptly described as "a shambles".

Shambles has never been a pleasant word: derived from a term for a bench, its original meaning is of that item of furniture as it is found at a butcher's: that is, a scene of quite literal carnage.

Malcolm Tucker: Originator of the term omnishambles

Worse still is an omnishambles, a term coined by writer Tony Roche for Malcolm Tucker to utter in The Thick of It which rapidly found itself being used by real-life politicians, an embrace which made the show's creator Armando Iannucci "queasy and uneasy".

Labour has tried to avoid being seen to play a subsequent blame game, a term popularised by Alcoholics Anonymous as a playing-out of recriminations that is best avoided.

In that spirit, Jeremy Corbyn has described himself as "Monsieur Zen".

Zen is the branch of Buddhism which holds that you should look not to scriptures (or perhaps to manifestos), but to a person's own heart.

There is no little irony here, given the charge that Labour's campaign is stressing the scripture over the man. Which brings us to...

Airbrushing

In a natty parallel, while Labour is accused of airbrushing Corbyn out of the party's campaign, the Conservatives have been described as airbrushing the word "Conservatives" in favour of images of their own leader.

Airbrushing in politics used to be a much more literal business. For a despot to remove a rival from a photograph, all that was needed was a sharp scalpel.

But when it came to disguising your skulduggery, the airbrush was your friend, doing as its name suggests and spraying away to cover the evidence.

Nowadays, airbrush is used for metaphorical disappearance: if you've been removed from a picture, you're said to have been photoshopped (another proprietary term).

Digital tools for altering pictures are much more readily available than was the delicate airbrush, but that doesn't mean that anyone can use them - as Labour candidate Kate Hoey found this week when she tweeted a picture which was missing the head of rival candidate, Lib Dem George Turner - but not his legs, external.

Finally, for now...

The big six

In all the excitement over whether Theresa May's energy-cap proposal was a reheated version of an old Ed Miliband policy, word watchers were left wondering: why do we call those energy companies The Big Six?

The "six" part can be explained by counting them; allow Election Lexicon to explain the "Big".

The Big Six were originally the Big Four, and they weren't energy giants: they were the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St Louis Railway companies of the nineteenth-century US midwest.

It made for a snappier nickname than the merger's preferred CCC&StL anyway.