General Election 2017: Is Theresa May a 'Red Tory'?

- Published

Theresa May has said she wants the Conservative party to be the "voice of ordinary working people once again". That has prompted some to say she's a "Red Tory". But what does that tag mean and is it true?

Imagine the Tory party as an archaeological site. Dig down the layers and you'll find the free trade crusade of Pitt the Younger and the social reform of Sir Robert Peel; the "One Nation" conservatism of Benjamin Disraeli and Margaret Thatcher's embrace of the market.

More recently David Cameron's nebulous notion of a "Big Society" has added another layer of political silt.

So what will Theresa May's contribution to the Conservative Party story be?

Her new manifesto will give us clues, and striking interventions into corporate Britain have already been trailed - putting worker representatives on company boards, creating new rights for employees to request training and a cap on energy prices.

The phrase "Red Tory" comes from the work of an academic called Phillip Blond, who published a book in 2010 called "Red Tory: How left and right have broken Britain and how we can fix it".

Following the global credit crisis of 2008, Blond argued that both untrammelled free-market capitalism and traditional left-wing stateism had failed ordinary people. Instead, he said civil society needed renewal and the economy needed some morals.

For a time Mr Blond found a fan in David Cameron, who talked about empowering the voluntary sector and fixing a "broken society".

But the "Big Society" branding felt just that and earlier this month Phillip Blond said Cameron had abandoned the idea for austerity and a conventional continuance of Thatcherism.

That seems too harsh. The idea of devolving powers to English regions (metro mayors and the Northern Powerhouse), along with socially liberal reforms such as gay marriage, marked a break from the past.

But Blond clearly hopes Theresa May could be the "Red Tory" he's been looking for. Writing in the Observer earlier this month he described the concept as a mixture of social conservatism (defending and securing the family, the community and the nation) and a new economic offer to working people.

Blond suggests policies such as a through-life retraining offer for workers, a better path for women back to rewarding work after childbirth, an overhaul of competition law to help small businesses and tackling asset inequality.

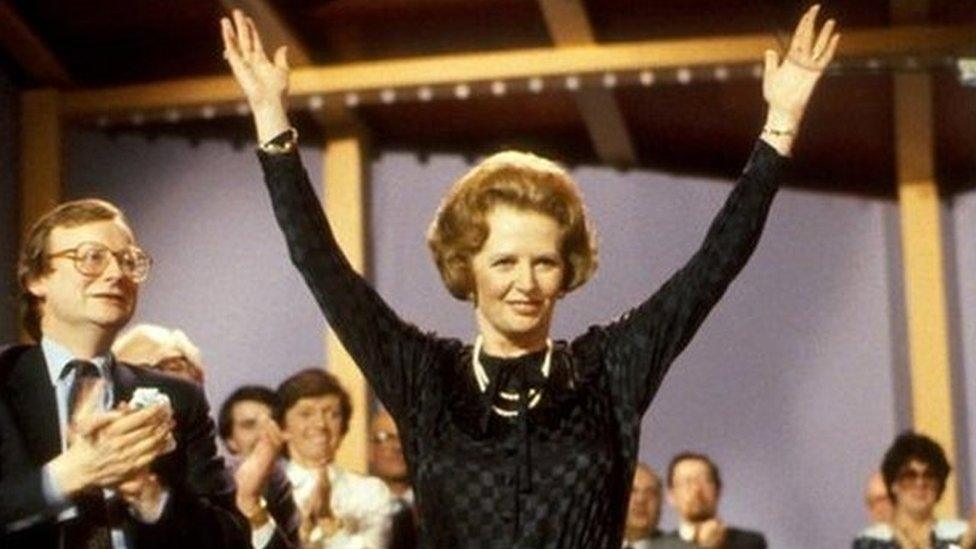

Margaret Thatcher appealed to aspirational working class voters

The new Number 10 is clearly doing some serious chin-stroking too. A few days ago, one of Ed Miliband's policy gurus Maurice Glasman - a Labour peer - had a cup of tea and a chat in Downing Street with Theresa May's co-chief of staff, manifesto writer and policy brain Nick Timothy.

'Blue Labour'

Glasman was responsible for the "Blue Labour" project that aimed to reconnect Labour to its traditional working-class voters and revive community solidarity. While "Blue Labour" has a greater emphasis on the role of the state than the "Red Tory" approach (and forgive me if this is getting unbearably wonky and abstract), both ideas have a similar goal and both believe the market economy needs to work better.

Nick Timothy seems to share their view that government has lost sight of the interests of many working people.

Before Theresa May was catapulted into Number 10 last year he wrote this very revealing piece., external The upwardly mobile Birmingham-born Mr Timothy said the Conservative party had to have a "relentless focus on governing in the interests of ordinary, working people".

He said on policies ranging from energy policy, house building, immigration, tax-credit cuts, the protection of pensioner benefits and the profile of spending cuts, David Cameron's government had made the wrong call. These are all useful clues to how Theresa May might govern.

Benjamin Disraeli is the father of "One Nation" Conservatism

She is not the first Tory prime minister to chase the support of working Britain. As the country adjusted to industrialisation in the 1870s Disraeli passed laws to prevent labour exploitation and recognise trades unions. Stanley Baldwin, too, emphasised the nation and social reform.

Mrs Thatcher took a different tack, appealing to the aspirational working and middle classes with council house sales, share ownership, lower taxes and patriotism. Of course Thatcher's critics argue her impact on working class communities and their industries was malign and Labour will not let the Tories try and claim the "people's party" mantle without a fight.

Jeremy Corbyn has promised to reverse recent Trade Union legislation, ban zero-hour contracts, impose "fat cat" taxes and more. Labour's policies are different but Mr Corbyn and Theresa May are fighting on the same turf.

I pinched the opening Time Team analogy from the late Ian Gilmour, a clever liberal Tory who loathed Mrs Thatcher's contribution to the Tory story.

But she was undoubtedly a winner. And if there's one characteristic that ties those Conservative prime ministers together it's a talent for adapting to public opinion and the changing political weather.

Gilmour once advised fellow Conservatives to "travel light". Not to get hung up on dogma and rigid principles. Pragmatism has been a consistent feature of the British Tory party for two centuries and it has kept them in power far longer than any of their opponents.

Two seismic recent events have changed the political weather - the 2008 financial crash and the vote to leave the EU.

The latter was in some part fuelled by the former and all the political parties are looking for ways to answer the concerns of voters feeling precariously employed, underpaid and angry about the way the state and the market is working for them.

The party that will succeed in this election is the one that best understands that mood and has plausible remedies to boot, regardless of the theoretical label attached.