General election 2019: A campaign unlike any other?

- Published

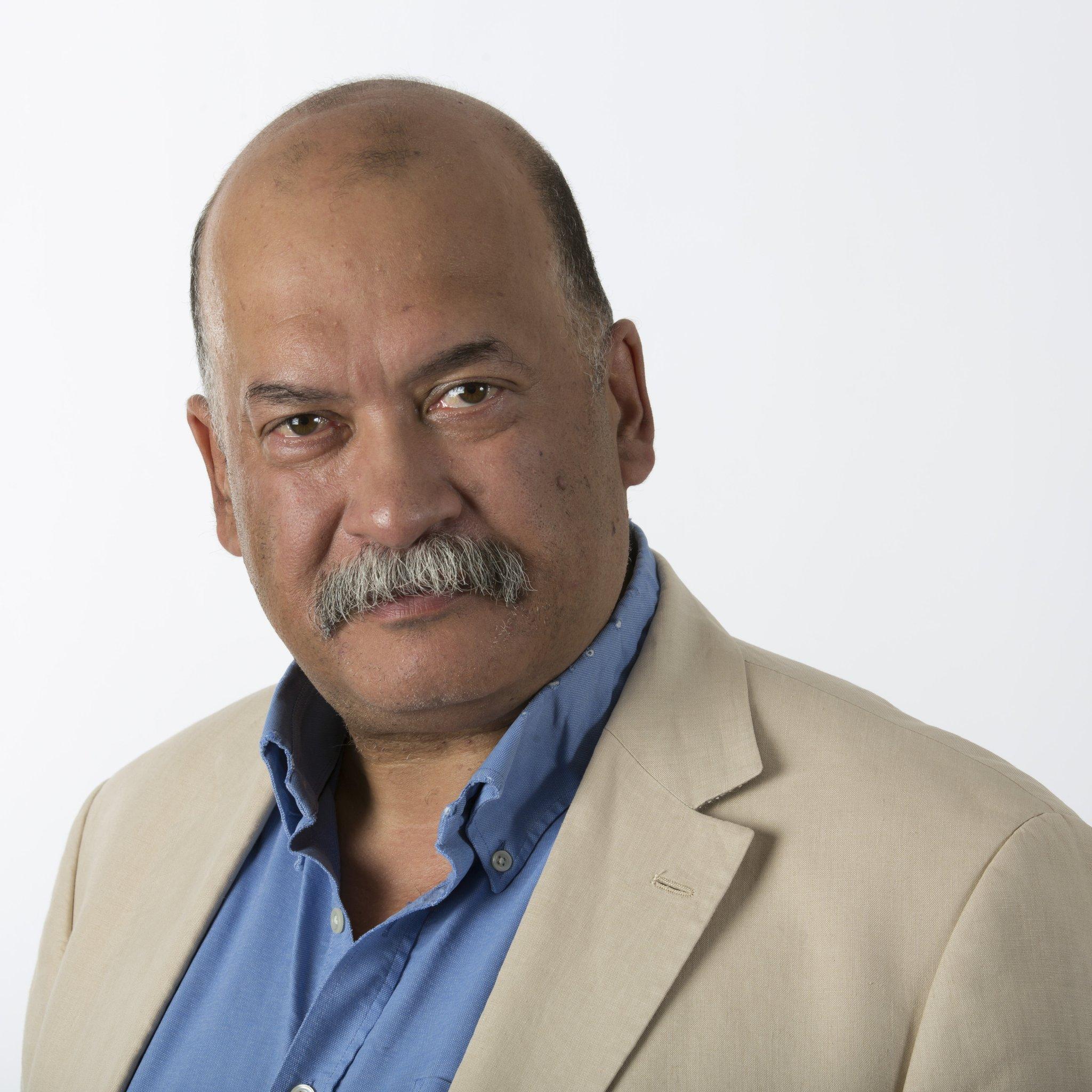

The prime minister has had plenty to chew on this week

Labour's latest "retail offer" of free broadband for all showed - if it still needed showing - voters are being handed a choice of rival ideologies as stark as any we've seen since Margaret Thatcher took on Labour's Michael Foot in 1983.

Younger voters may imagine this is what normal politics looks like. It isn't. Or at least, it wasn't.

All the parties are desperate to grab the attention of an electorate which has never trusted its politicians less, or been less tightly bound by old party loyalties.

So far, the 2019 general election has been unlike any in living memory.

Trust between people and politicians - as measured, for example, by the YouGov "Trust Index" - has never been lower in modern times.

Party loyalties have never been looser.

Monday's quarterly GDP figures set the economic tone. Annual economic growth at 1% was nothing to celebrate, even if the UK hadn't actually tipped into recession.

And yet the spending arms race picked up speed; the Tory promise of £34bn extra cash for the NHS overtaken this week by Labour's £40bn.

So, the rivals are now racing desperately in the face of economic and political headwinds, compounded by the almost bottomless uncertainties of Brexit.

The Conservative slogan "get Brexit done", for example, glosses over the fact that, even if Boris Johnson wins a majority on 12 December and manages to pass his EU divorce deal intact, it would be just the start of tougher trade negotiations than any we've seen so far.

The prime minister's assessment on BBC Breakfast that there's "bags of time" to achieve a comprehensive EU trade deal may be true, though plenty of experts don't believe a word of it.

If those experts are right, we would again be looking at the possibility of a no-deal Brexit at the end of next year.

CONFUSED?: Our simple election guide, external

POLICY GUIDE: Who should I vote for?, external

REGISTER: What you need to do to vote

Immigration also dominated the argument this week.

Pro-EU parties like the Lib Dems and the SNP unapologetically, defiantly, banged their drums for freedom of movement.

The Conservatives and Labour, both so wary of offending voters in Leave-supporting constituencies, spent much more time condemning each other's migration policies than explaining the consequences of their own.

The Labour leader has been put on the spot over immigration and Scottish independence

Would the Tory promise of a points-based immigration policy mean lower levels of immigration?

Priti Patel said yes, eventually and rather quietly. There were no numbers attached.

Mr Corbyn would only say Labour's plan would be "fair". He meant cutting numbers was not the point, even if a lot of potential Labour voters think it is.

Under his leadership, Labour is more interested in enforcing fair wages, stopping home-grown workers being undercut by migrants and giving trade unions more power to help set pay rates in companies across the UK.

Lib Dems punching their weight?

Where is the election heading, just over a week into the official contest?

You only a need a memory stretching back as far as Theresa May's 2017 campaign to realise making hard and fast predictions is a game for mugs.

The Brexit Party's decision to pull candidates out of 317 Tory-held constituencies this week was a help to the Tories, but not enough to hand a sure victory to the Conservatives.

The Lib Dems are fighting to win, while ruling out any kind of deals if they do not

Now, leading Brexit Party players are claiming they've been quietly offered peerages, jobs and, in the case of Ann Widdecombe, a role in future trade talks if only they'd back off.

The Conservatives deny it. She says she's a practising Catholic and she'd swear on a bible it's true. Call her a liar if you wish. I'll hold your coat.

The Lib Dems have been campaigning on familiar themes, including climate change. They're hoping, of course, to hold the balance of power in the new Parliament, and use it to frustrate Boris Johnson, or force out Jeremy Corbyn.

It's not inconceivable that their leader Jo Swinson could become a political "kingmaker".

Local council by-election results this week suggest the Lib Dems may, just may, outperform their poll ratings. It wouldn't be the first time.

Flood fallout

There's still nearly a month of this to come. Already, Jeremy Corbyn has carried out 20 campaign visits, often targeting marginal Tory seats.

That's one third more than Boris Johnson and more than double the Lib Dem leader.

Those numbers will surely even out. All of them have been to areas hit by the floods this week. The prime minister's response was strongly criticised by his opponents. Then he promised grant money for councils and businesses.

Mr Johnson also committed some 100 troops to help out, useful no doubt; maybe even more useful than the similar number of party leaders and members of their campaign entourages who've converged on the stricken areas of the Midlands and South Yorkshire in recent days.

Or is that too cynical?