General election 2019: Could undecided voters change the election?

- Published

Will this election be decided by voters yet to make their mind up?

The 2017 election did not turn out the way anyone expected.

When the election was announced, polls showed the Conservatives with a massive lead over Labour.

In the end, the Conservatives lost their majority and there was a hung Parliament.

Support for Labour had steadily increased throughout the campaign.

In 2019, with just over a week to go, could undecided voters make a crucial difference at this late stage?

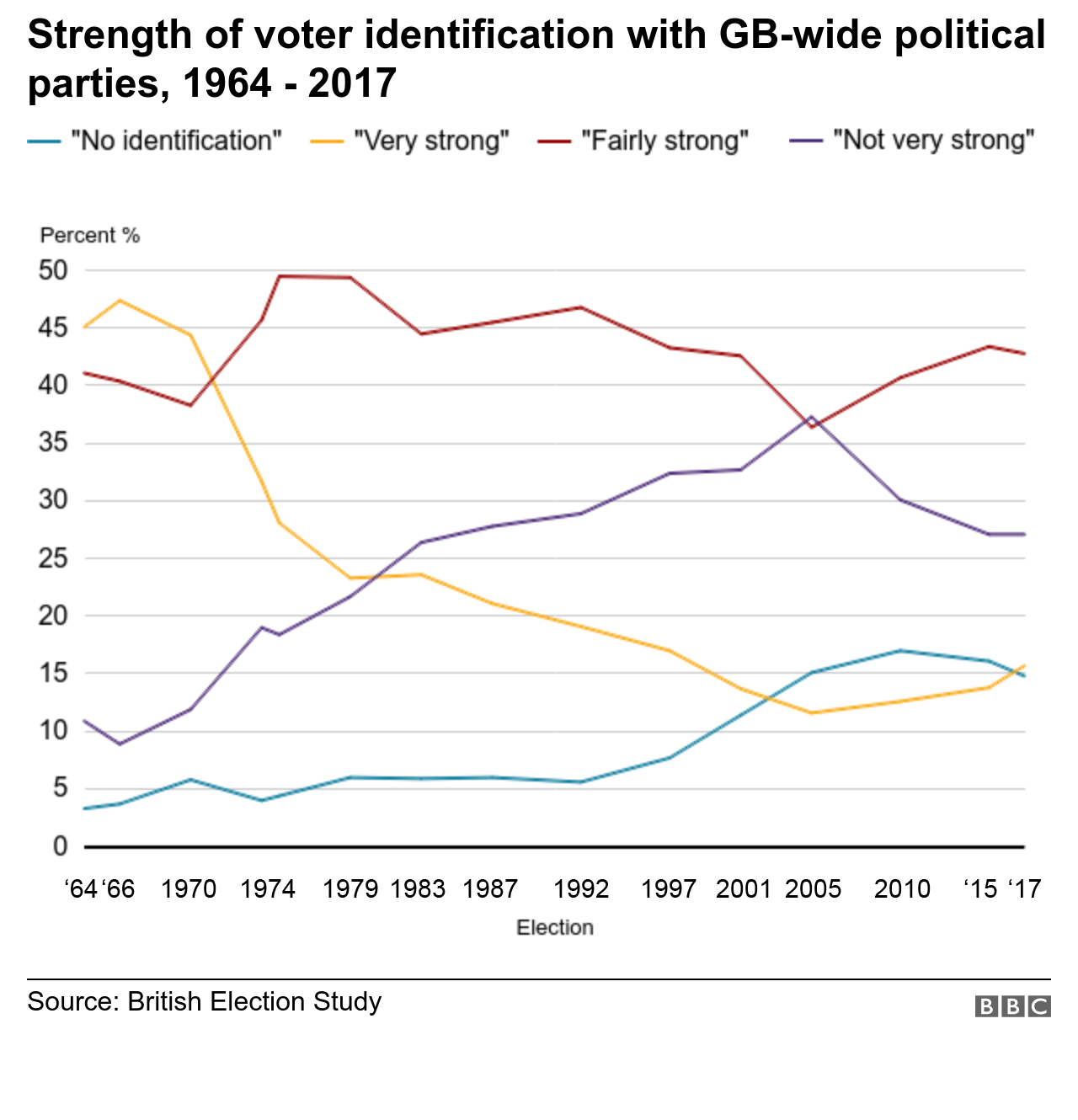

Is attachment to parties weakening?

It used to be the case that few people changed their minds during election campaigns. Most voters had a long-term stable psychological attachment to a political party and they voted for the same one, election after election.

This no longer seems to be the case. British Election Study data indicates, external that currently just 16% of Britons feel a very strong party identification. Compare this with the mid-1960s, when almost half of the UK population had a very strong party attachment.

In 1966, only about 13% of voters switched parties between elections. In 2015, that figure was 43% - and in 2017, it was 33%. Overall, across the past three elections, external, almost half the UK electorate (49%) voted for more than one party.

In 2017, a significant number of voters changed their minds during the campaign itself - and the same may yet happen in 2019.

A recent YouGov poll, external estimates 13% of the electorate who intend to vote have yet to decide for whom. This group of voters is highly likely to switch parties from last time.

Additionally, a recent Ipsos Mori poll, external suggested 40% of voters might still change their mind between now polling day:

28% of Conservative supporters

46% of Labour supporters

60% of Liberal Democrat supporters

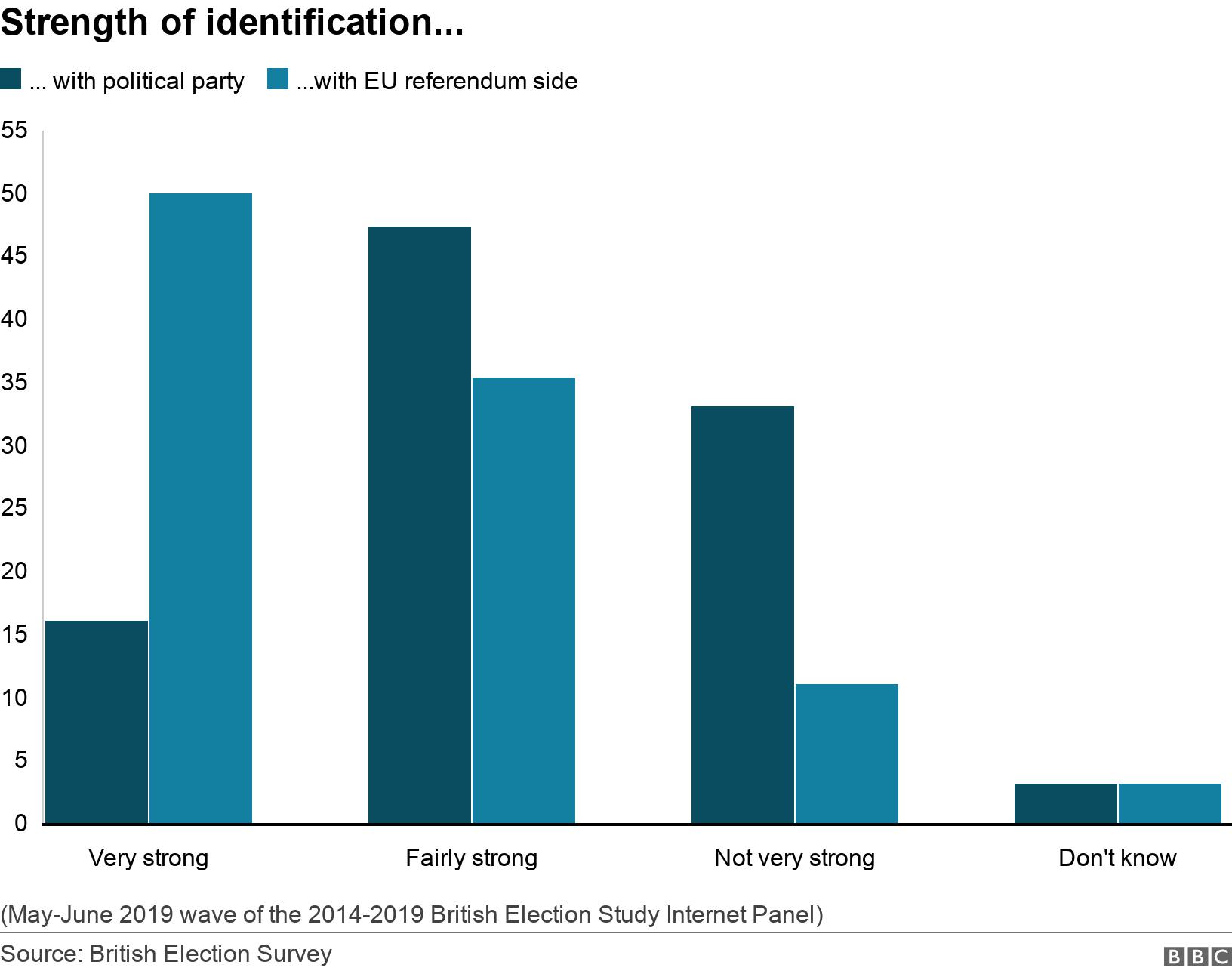

What about the Brexit effect?

Brexit may well play a part in how undecided voters make up their minds, because identification as leavers or remainers appears to have outstripped party allegiance.

The British Election Study suggests 50% of people across the UK strongly identify with one side of the debate, which Prof Sir John Curtice calls the emotional legacy of Brexit, external.

The extent to which this election is dominated by the issue of Brexit could have a substantial impact on the result.

In 2017, Labour managed to shift the debate from Brexit to austerity.

In the process, it picked up many votes in the latter half of the campaign from younger voters, external and women, external hostile to public-spending cuts.

The dominant news stories of the past few days of this campaign - and how the parties manage to direct and shape election coverage - could be critical in helping a significant chunk of the electorate make up their mind.

Whose vote could be up for grabs?

Generally, there is little difference between men and women's electoral participation - but women are apparently more likely to be undecided voters than men.

In the run-up to the 2017 election, 18% of women and 10% of men did not know for whom to vote, according to the polls.

Men and women turned up to vote in equal proportions.

But, like many of those who made up their mind later on in the campaign, more women than men voted Labour, external.

13%Voters have yet to make up their mind

19%of female voters are undecided

7%of male voters are undecided

16%of C2DE (working class) voters are undecided

12%of ABC1 (middle class) voters are undecided

In 2019, again the polls suggest a smaller proportion of women than men have made up their minds, external - 19% of women say they don't know for whom to vote, compared with 7% of men.

People in working-class jobs are also disproportionately represented among the undecideds - 16% say they don't know for whom to vote, compared with 12% of middle-class voters.

And these undecided working-class voters could make a significant difference to the result, especially in marginal northern English seats where Labour, Conservative, the Brexit Party and the Lib Dems are all competing for their votes.

How can the parties reach undecided voters?

There is a great deal of research suggesting the local constituency ground war, and particularly face-to-face contact, matters for mobilising voters - and traditional door-knocking works, external.

And although only a very small number of voters' minds are changed by local canvassing, they can make a crucial difference in marginal seats.

There also is strong evidence voters prefer candidates with local connections - research has even indicated the distance between a voter's home and the candidate's residential address is a predictor of their level of support.

But we know much less about the impact of targeted messaging on social media.

In 2017, Labour was able to compensate for the Conservatives' greater social media spend with more boots on the ground and more individuals sharing posts for free.

We don't yet know what the fallout of the online - and offline - campaign of 2019 will be. And without a system for publicly sharing, we might never know.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Prof Rosie Campbell is director of the Global Institute for Women's Leadership at King's College, London

Edited by Ben Milne