General election 2019: What was Britain like at the last December poll?

- Published

The election was held on 6 December 1923

The 2019 General Election will be the first to be held in December since 1923. What was Britain like back then and how did the election turn out?

It was the year Flying Scotsman was built and Wembley first hosted the FA Cup final.

George V was halfway through his 26-year reign as king and the British empire covered one fifth of the world's land including Canada, India, Australia, New Zealand and large parts of Africa.

Domestically, it was a time of turmoil with the effects of World War One still being keenly felt five years after the end of the conflict, in which about 700,000 British men were killed.

General elections were held in 1922, 1923 and 1924

Britain was paying £34m a year in repayments for the war loans it had taken out (these were not finally cleared until 2015) while its traditional industries such as steel, coal and iron were failing to compete with the cheaper manufacturers from abroad.

"Britain was the first country in the world to have an industrial revolution," says Harry Bennett, associate professor of history at Plymouth University.

"They were still on first and second generations of technology while later countries to develop were on more efficient third or fourth generations.

"By the 1920s we had been intensively extracting coal for 100 years so what was left was now harder and more expensive to get to meaning ever deeper mines and more complex geology."

You may also be interested in:

Then there was the war, Prof Bennett said.

"Businesses had to repurpose themselves to make war weapons, they lost skilled workers and the time that other countries like America could spend improving their industries. After the war there was an economic boom which when you think about it makes sense. In shipbuilding for example they had to replace the tonnage lost during the war, but once the fleet is back up to strength that boom turns to bust."

Bust was the order of the day by 1923 with some 8% out of work (compared to about 3.8% now), while farmers in Norfolk were striking over low wages and there was a general resentment among the working classes about poor pay.

The disgruntled working classes were turning towards the new Labour party, prompting fears of a Russian-style revolution with the rich claiming they would flee the country if Labour won power (not unlike claims made in the event of a Jeremy Corbyn victory, external).

George V was half way through his 26-year reign

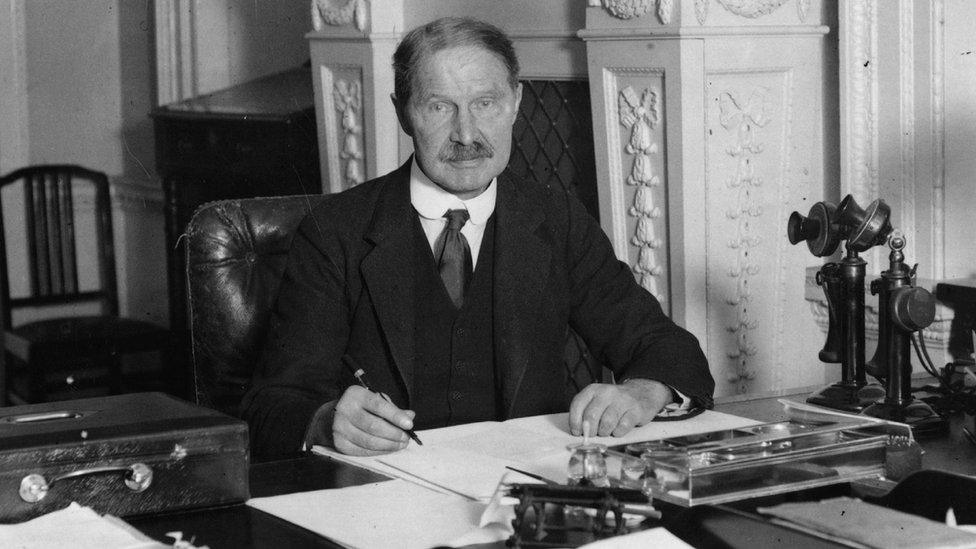

The Conservative government of Andrew Bonar Law had been elected in November 1922 with a 55.9% majority, but barely 200 days later he resigned after being struck down with throat cancer to be succeeded by the chancellor of the exchequer Stanley Baldwin.

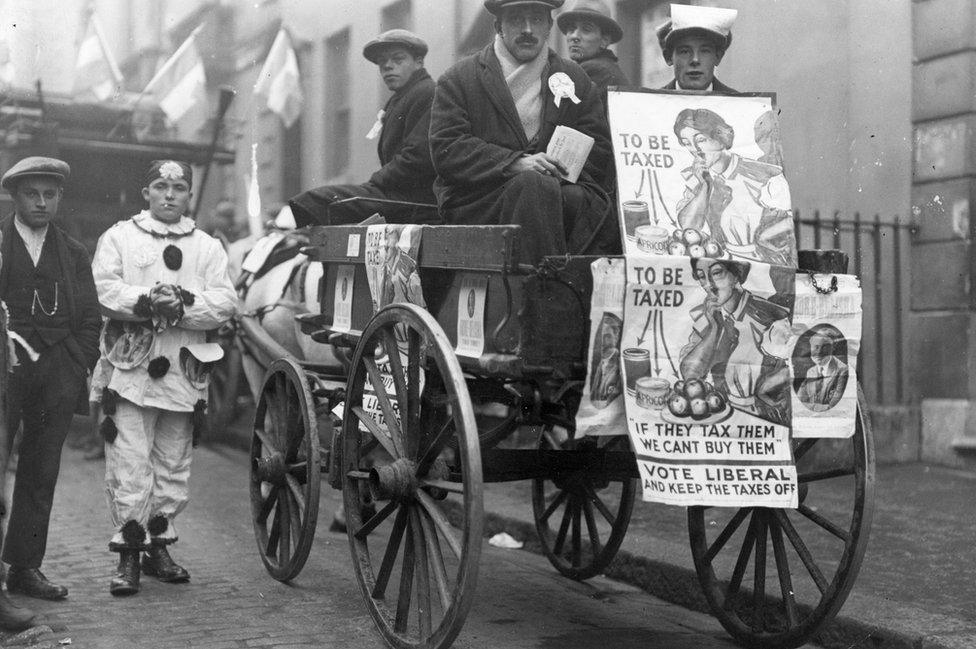

Baldwin said the best way to tackle the problems was by introducing import tariffs to make the cheaper foreign goods more expensive and stimulate home production instead.

Andrew Bonar Law was the country's shortest serving Prime Minister in the 20th Century

It was a controversial and divisive move, Prof Bennett says, because it could mean an "open season" on free trade with tariffs also coming on food, which would hit every person in their pocket.

"As an island nation Great Britain could not produce enough of its own food, there were too many people," he says.

"I would say the potential scale of change for people is equivalent in today's terms to the NHS being sold to private medical companies."

Despite having a majority in the House of Commons, Baldwin decided to effectively hold a referendum on the tariff issue, which was after all a big statement about the country's future foreign policy and position within the world.

"It was like Brexit before we ever came up with the word Brexit," Prof Bennett says, adding: "He was saying to the public 'it's up to you'."

It was also personal for Baldwin, Prof Bennett says, and a bid to remove the accusation from the mouths of his opponents that he was not an elected prime minister but had rather fallen into the role because of the terminal illness of Bonar Law.

The election was duly called for 6 December.

General election 1923: Crowds gather to watch result

It was not a particularly cold winter, more dull and drizzly than crisp and blindingly white, although there were occasional snow and sleet flurries with December seeing a mean temperature of 3.9C.

Houses were decorated with festive bunting and heated by coal fires, shopping streets bustled with rattling trams and women wore ankle-length skirts and cloche hats.

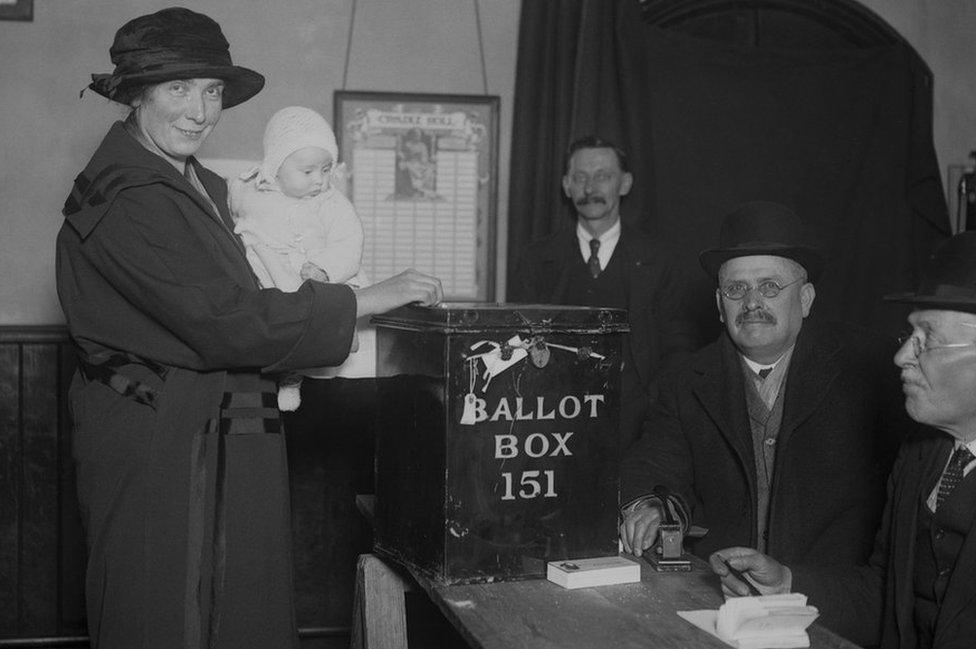

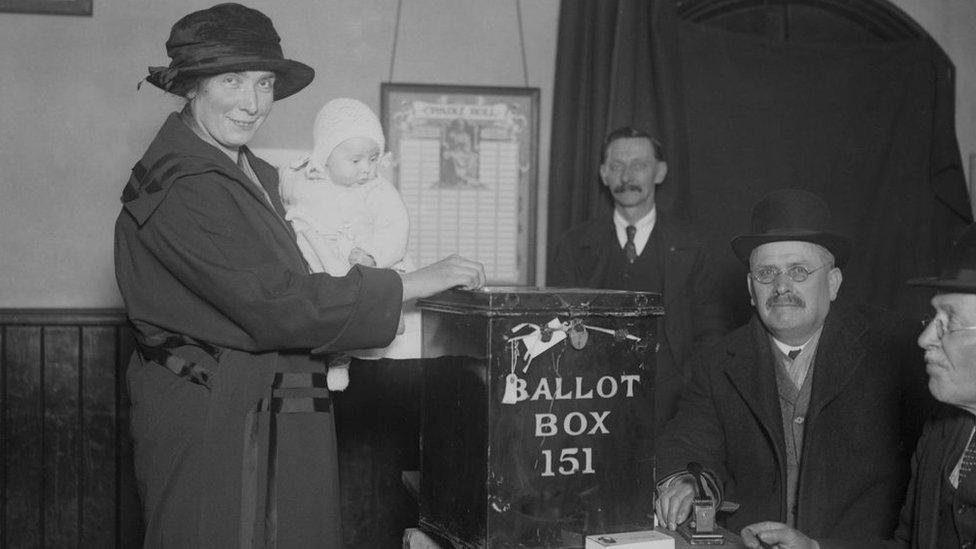

The Representation of the People Act five years previously had given them the vote, although not all women - only those aged 30 or over who owned property worth at least £5, which accounted for about two thirds of the nation's women (full voting rights would come in 1928).

About two thirds of the nation's women were eligible to vote

Voters had the choice of three main parties.

Baldwin's Conservatives said introducing tariffs would tackle the unemployment issue by sparking into life the country's industries which, he said, had been "exposed to a competition which is essentially unfair and is paralysing enterprise and initiative".

"No Government with any sense of responsibility could continue to sit with tied hands watching the unequal struggle of our industries," his manifesto said.

Stanley Baldwin said tariffs were the best way to tackle unemployment

As well as tariff changes, which would not "in any circumstances" be introduced on wheat, meat, oats, flour, cheese, butter or eggs, the Conservative manifesto also promised to:

Pay £1 an acre to farmers to keep up the wages of agricultural workers

Develop cotton growing across the empire

Speed up building of Royal Navy light cruisers to stimulate declining shipbuilding

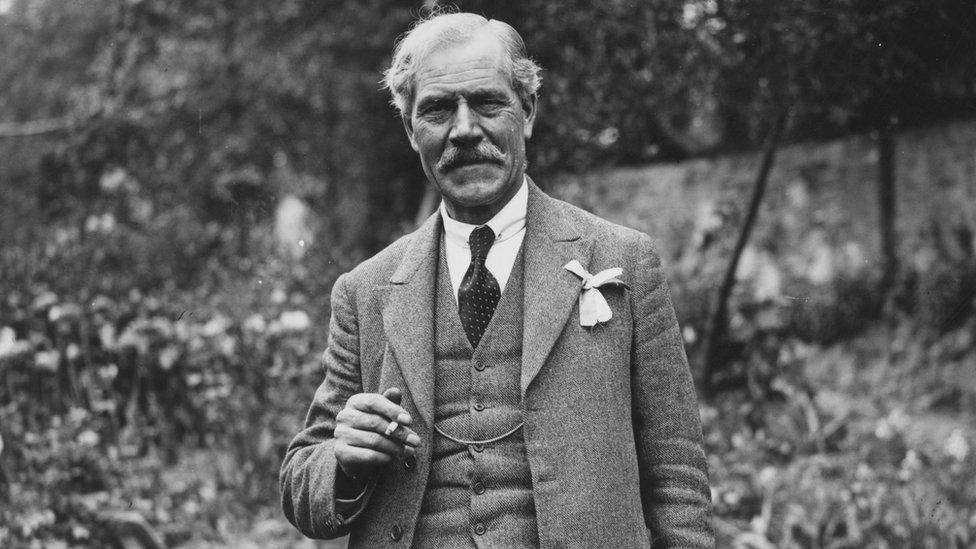

The tariffs were opposed by the newly risen Labour, led by Ramsay MacDonald, who said calling for an election showed how, after a "year of barren effort", the Conservative government had "admitted its inability to cope with the problem of unemployment".

"Tariffs are not a remedy," the Labour manifesto declared.

"They are an impediment to the free interchange of goods and services upon which civilised society rests."

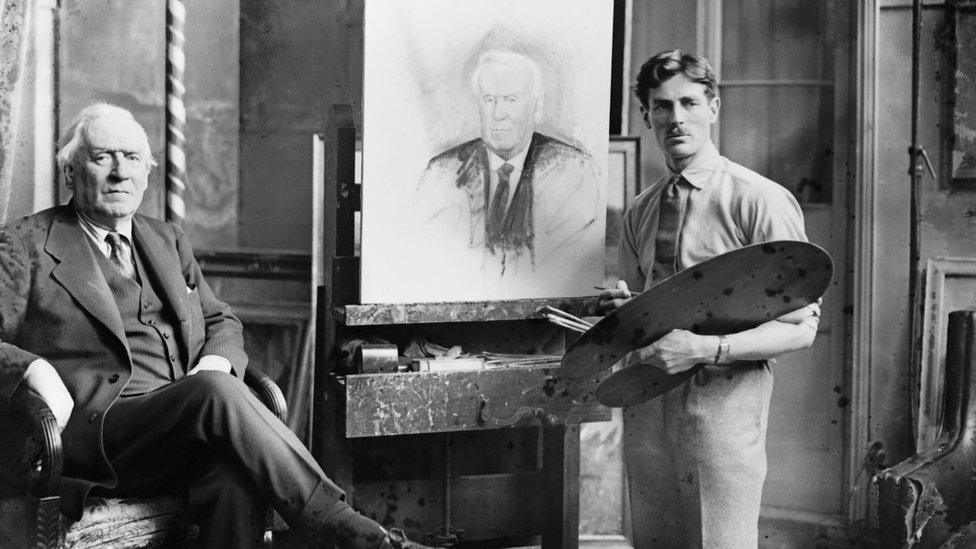

Ramsay MacDonald opposed the tariffs

Tariffs, Labour argued, "foster a spirit of profiteering, materialism and selfishness" while also adding to the inequality in the "distribution of the world's wealth".

Labour instead proposed national work schemes, "adequate maintenance" for those unable to obtain work while they search for a job and "full educational training" for young people.

The party also promised regulating farm wages and reducing the public's payment of war debt by introducing a tax on war fortunes - the vast amounts of money made by some through the likes of munitions manufacturing.

Although leader of the third-choice party, Herbert Henry Asquith would have a big say on who became Prime Minister

The voters' final choice was the Liberal party led by Herbert Henry Asquith. The party had run the country in a coalition with the Conservatives during and after the war, but once that relationship broke down the party itself split.

It was the tariffs issue at the heart of the 1923 election that actually unified both wings of the Liberals beneath Asquith, Prof Bennett said, with the party claiming the Conservative arguments about tariffs being a "cure" for unemployment were "unproved and unproveable".

"High prices and scarcity can only lower the standard of living, reduce the purchasing power of the country, and thereby curtail production," the Liberal manifesto argued.

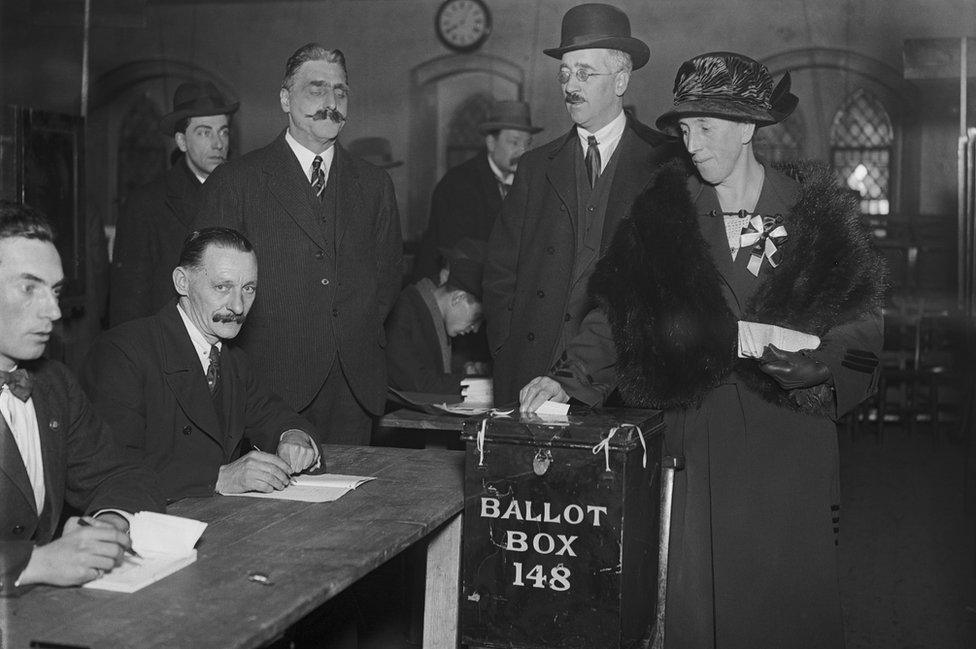

One Mrs Mawbey was the first person to cast her vote at a polling station in Dulwich

Election day itself was mild and dry with 71% of the electorate turning out to vote.

The result was disastrous for Baldwin.

Instead of strengthening his overall majority he lost it, securing 42% of the seats while Labour won 31% (up from 23%) and the Liberals 26% (up from 10%).

Baldwin was further disappointed when the Liberals, who still had a toxic relationship with the Conservatives following their post war-coalition fallout, refused to back him and instead sided with the opposition, enabling MacDonald to found the country's first ever Labour government.

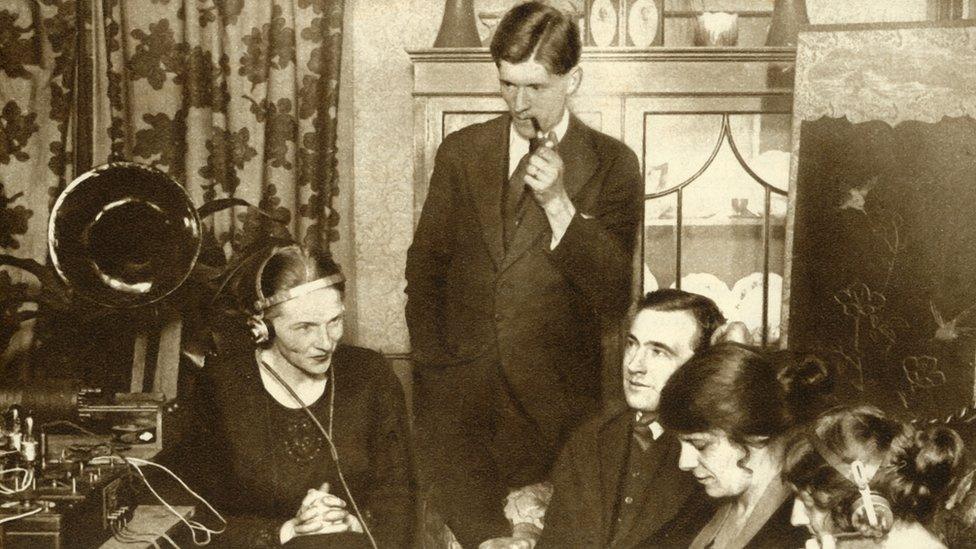

Families listened to the results on the wireless

Just 11 months later, Baldwin and the Conservatives were back in power, this time with a near 67% majority, after a third general election in as may years precipitated by a colossal fall out between Labour and the Liberals which resulted in a vote of no confidence in MacDonald being passed by the commons.

But MacDonald could still be pleased with his short period in office, Prof Bennett said.

"He showed that a Labour government could be responsible and competent. They did not hang the rich aristocrats from lampposts or seize money, the worst fears and hysteria beforehand had not been borne out."

The December 1923 election came amid a period of angry argument between divided political parties, bitter disagreement about Britain's place in the global market and Christmas preparations.

"There are very strong echoes with what is happening today," Prof Bennett said.

The first Labour government lasted less than a year

- Published3 November 2019

- Published11 December 2019

- Published6 December 2019

- Published18 November 2019