General election 2019: Will people vote tactically in Scotland?

- Published

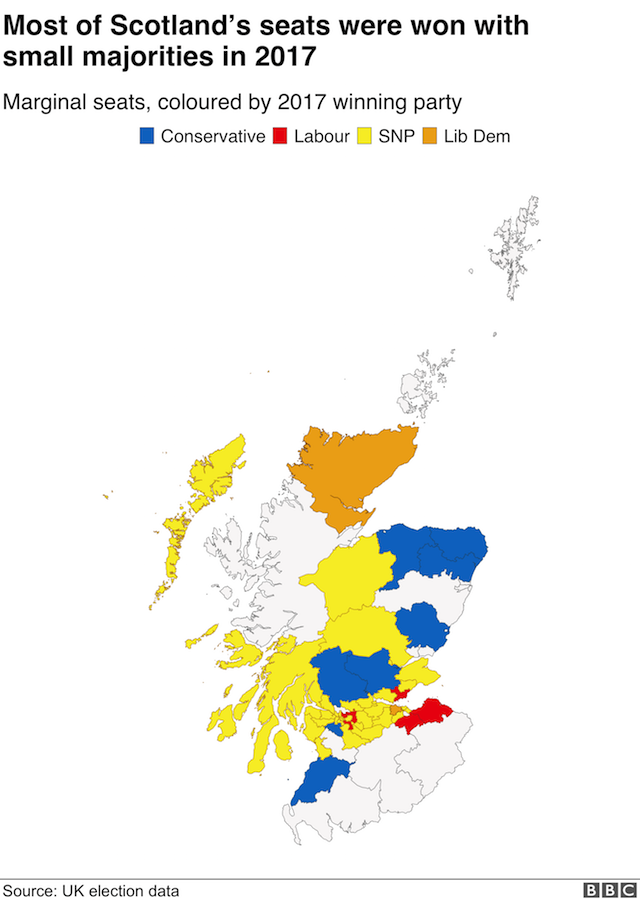

One of the striking features of the electoral landscape in Scotland is that nearly every Westminster seat is marginal.

At the last election, the winning party's majority represented less than 10% of the vote in no less than 46 of the country's 59 Westminster seats.

And in most of these seats, quite a substantial share of the vote went to whoever came third. In the 15 instances where the SNP and the Conservatives shared first and second place in the 2017 election, Labour on average won just under a fifth of the vote. Similarly, in the 28 seats where the battle was between the SNP and Labour, just over a fifth of the vote was captured by the Conservatives.

As a result, the outcome of the election north of the border could potentially be heavily influenced by 'tactical voting'.

If voters whose first preference party looks set to come third (or even worse) switch from that party to one that seems better placed locally to defeat a party that they particularly dislike, they can make a difference to the result in a constituency.

Such tactical switching - motivated by voters' views on the constitutional question - was in evidence at both the last two UK elections in Scotland.

In some seats which the Liberal Democrats were trying to defend in 2015, voters who might otherwise have backed the Conservatives seemingly voted instead for the Lib Dems, who were the Tories' coalition partners at the time.

In contrast, in 2017 the Liberal Democrat vote in some seats was squeezed quite heavily to the Conservatives' advantage. This was most likely because voters had come to the conclusion that, in the wake of the sharp fall in Lib Dem support in 2015, the party was no longer competitive locally.

Similarly, though on a smaller scale, there were some signs in 2015 of Conservatives opting to vote Labour in seats that Ed Miliband's party was trying then to defend. In 2017 the opposite pattern was sometimes in evidence in seats where the Conservatives were now relatively strong locally and Labour's vote had fallen away.

Most tactical voting seems to have been directed at trying to defeat the SNP. This is a reflection of the fact that there are three different parties that support Scotland's continuing membership of the Union and who between them fragment the pro-Union vote, whereas the SNP face relatively little competition for the support of those who back independence. The pro-independence Greens won just 1% of the vote in 2015 and only stood in three seats in 2017.

What is the picture in Scotland?

The SNP secured a huge landslide north of the border in 2015, taking 56 out of Scotland's 59 seats. Labour, the Tories and Lib Dems clung on to one each. The election saw the SNP leapfrogging the Lib Dems - who were decimated after five years in coalition with the Conservatives - to become the third-largest party at Westminster.

And while the SNP's position slipped back somewhat in 2017, down half a million votes and 21 seats, they still retained that position as Westminster's third party with 35 MPs. That said, the 12 seats gained by the Scottish Conservatives ultimately enabled Theresa May to hold on to power.

The SNP came second in every seat they failed to win, so as well as defending their 35 incumbents they will be seeking to make gains in other areas - not just the 13 Tory seats, but the seven held by Labour and the four held by the Lib Dems.

But what are the chances of significant levels of tactical voting this time?

Certainly, some voters propose to vote that way. In a recent poll Ipsos MORI found that one in eight (13%) say that they anticipate voting tactically, external.

Of those people, 17% said they would vote no in a second independence referendum - much higher than the equivalent figure (7%) among supporters of independence. That suggests that, once again, tactical voting is most likely to be motivated by a wish to defeat the SNP.

However, the reported level of tactical voting in that poll among unionist voters is lower than was recorded when Ipsos MORI conducted a similar poll before the 2017 election. Then, nearly one in four (24%) of supporters of the Union indicated they were proposing to vote tactically.

That suggests that some of those who voted tactically against the SNP last time will be less willing to do so this time around.

One reason why this might happen is Brexit. The pro-Union parties disagree on this issue. The Conservatives back Britain's exit from the EU under the terms that Boris Johnson has negotiated, while Labour and the Liberal Democrats believe the issue should be put to another referendum.

If the Brexit debate matters to voters, they may be reluctant to vote tactically for a party that takes a different stance from their own on the subject, even though it may have a better chance of defeating the SNP locally.

Polling suggests that voters' stance on Brexit is more likely to be reflected in how they propose to vote at this election than was the case two years ago.

Two polls of voting intentions in Scotland have been conducted during the current campaign. On average, they suggest that the level of support among Leave voters for the Conservatives (at 58%) is 12 percentage points up on two years ago. In contrast, the party's support is down four points (to just 14%) among those who voted Remain.

Conversely, support for the Liberal Democrats is up seven points among those who voted Remain, while it is down two points among those who voted Leave.

These figures suggest that Conservative supporters who back Brexit are likely to be reluctant to switch to the Liberal Democrats, while Liberal Democrats who oppose Brexit will be disinclined to switch to the Conservatives. Similar considerations may also influence some Labour supporters, although they are much more of a mixed bunch in their attitudes towards Brexit.

So, despite the country being a hive of marginal seats, there is no guarantee that tactical voting will play an especially prominent role in the election in Scotland next week.

In a contest in which not one, but two cross-cutting constitutional issues are influencing how people vote, switching between parties could well prove harder to do.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Sir John Curtice, external is professor of politics, Strathclyde University, and senior research fellow at NatCen Social Research, external and The UK in a Changing Europe, external.