General election 2019: Why do politicians always say the same thing?

- Published

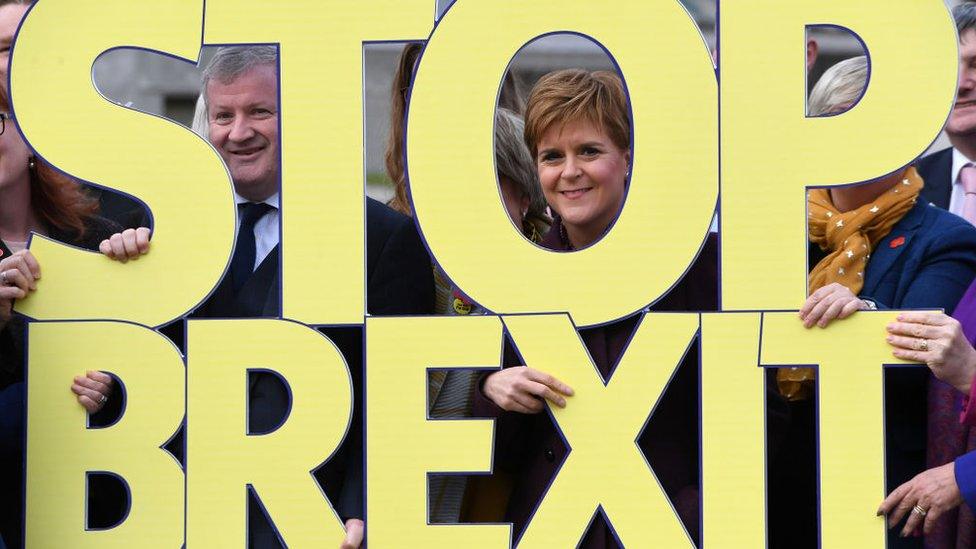

The SNP have put Brexit and independence at the heart of their campaign - and every speech and statement

With one week to go in the election campaign, Scotland's parties are desperate to hammer home their key messages to voters. Where do their slogans come from, and why do they stick to them so religiously?

Joy in repetition

Certain phrases can become very, very familiar during election campaigns.

Almost every SNP speech, press release and media comment going back to day one contains the words "escape Brexit", "lock Boris Johnson out of office" and "put Scotland's future in Scotland's hands". We're talking about three or four statements per day, all containing those exact same phrases.

Compare and contrast:

Nicola Sturgeon, 2 November: "A vote for the SNP is a vote to escape Brexit, and to put Scotland's future in Scotland's hands - not Boris Johnson's."

Nicola Sturgeon, 6 December: "A vote for the SNP is a vote to escape Brexit, and to put Scotland's future in Scotland's hands - not Boris Johnson's."

Everybody does it.

The Scottish Conservatives have based their entire campaign on opposition to an independence referendum, and indeed could actually be re-using a lot of their "no to indyref2" material from 2017 if it didn't have ex-leader Ruth Davidson's face all over it.

Labour candidates struggle to utter a sentence without opening with "real change" and tacking "for the many, not the few" on the end.

And the Lib Dems have pledged more or less daily to "build a brighter future" by stopping Brexit and independence.

You'll never guess what the Scottish Tory slogan is

Why does this happen?

Politicians are very keen to stay on-message. These lines you hear again and again don't happen by accident - they're chosen very carefully, after plenty of stress-testing and scrutiny in focus groups.

These slogans need to encapsulate what the party stands for in a concise, memorable phrase - and, importantly, be robust enough to stand up to the rigours of a six-week campaign.

Theresa May was ultimately haunted by her own "strong and stable" mantra, because it was quite easy to add a question mark whenever she had a wobble.

Once chosen, politicians have to repeat their favourite lines over and over - because most of the time, most people just aren't listening.

Brighter, brighter, brighter

Each week, Lord Ashcroft conducts a poll asking "what incidents, events, stories etc. have you noticed from the election campaign in the last few days?"

This week, it was 40% "none", with "lies/don't trust politicians" in second place at 17%.

The week before, it was 39% "none", and 19% "lies". "Leaders debates" and "manifestos" did at least manage to scrape into double figures, on 15% and 10% respectively.

The week before that? 39% "none" again (with "public spending promises" in second on 13%), and in the first week of the campaign it was 42% "none", with nothing else making it over 5%. Even "lies" struggled that week.

How is the humble politician to burst through this brick wall of indifference? How can they get their favoured message through to the disinterested masses?

Repetition, repetition, repetition.

Real change - but not to the messaging

Regional variations

Are the messages being put out in Scotland different to those UK-wide? To an extent.

The Conservatives obviously don't tend to play up their opposition to independence quite as heavily when campaigning in England and Wales, although Boris Johnson does love to mention the prospect of a Corbyn government propped up by the SNP leading to "two referendums in 2020".

Instead, his go-to slogan is "get Brexit done" - something which might not translate quite as well to Scotland, where 62% of voters backed Remain in 2016.

Labour's "real change" message goes out UK-wide, but there is a difference in that it's targeting change away from a Conservative government at Westminster, rather than the SNP one at Holyrood. Hence why Scottish Labour try to reinforce their message north of the border with the phrase "when Labour wins, Scotland wins".

The Lib Dems meanwhile lean heavily on their "stop Brexit" theme right across the country. It does get an extra flavour of "...and independence" in Scotland, but given Jo Swinson is defending a Scottish seat and pops up campaigning there quite regularly, this has really become part of the party's core message.

Going off message

For all that people often claim they'd like politicians to rip up the script, kick over the autocue and shoot from the hip, it rarely actually goes well for those who do.

Observe the trouble Labour has had in putting across its position on Scottish independence. There actually is a fairly stable kernel of policy at the heart of it all, but because the party hasn't been precise in its messaging it's looked like they're all over the shop.

The party doesn't want to have "indyref2" straight away, should they end up in government backed by SNP votes, but wouldn't stand in the way of it if pro-independence parties win a stonking mandate in the 2021 Holyrood elections.

But when it comes to articulating this, they've said everything from "not in the early years" of a Labour government, to not in the first (five-year) term, to not next year, to not inside two years - almost every possible variation you can think of, while still theoretically still fitting into that overarching "not now" position.

The result has been attacks from both sides - the Conservatives constantly run attack ads claiming Labour are weak on the union and bound to cave in to Nicola Sturgeon's demands, and the first minister herself openly mocks Mr Corbyn about it.

Basically, Labour has been punished for not having a clear line and sticking to it.

Do politicians rely as much on their slogans when out "on the doorsteps"?

Is it different on the doorstep?

Election campaigns can traditionally be divided into two different approaches by parties - the "ground war" of door-knocking, leafleting and canvassing, and the "air war" of ideas and debates which are beamed out nationwide.

Both are important. Parties tend to do well nationally after impressing the electorate as a whole, but local efforts can make all the difference in actually getting people out of the house and into a polling station.

This is particularly true when you live in a nation of marginal seats like Scotland, where 46 out of 59 constituencies have single-digit majorities.

All of the points discussed above relate to the air war; the broad-brush messages put out by the party leadership, rather than the conversations activists are having with punters "on the doorsteps".

On the ground, messages are typically delivered by local candidates and activists, and can be tailored far more specifically to local concerns - so there's less reliance on slogans.

For example, while the SNP's air war has been all about "putting Scotland's future in Scotland's hands", if you look at the leaflets they're sending out in Tory-held seats there's little to no mention of independence.

The Lib Dems have tailored bar charts claiming they're winning literally everywhere, and Labour's candidates have taken to hyper-local targeting through a slew of Facebook ads.

With one more big drive to "get out the vote" before 12 December, don't be surprised to hear the familiar phrases above more than a few times in the days ahead - or to find the candidates on your doorstep.

- Published5 December 2019

- Published20 November 2019