What happened to Rand Paul's 'libertarian moment'?

- Published

- comments

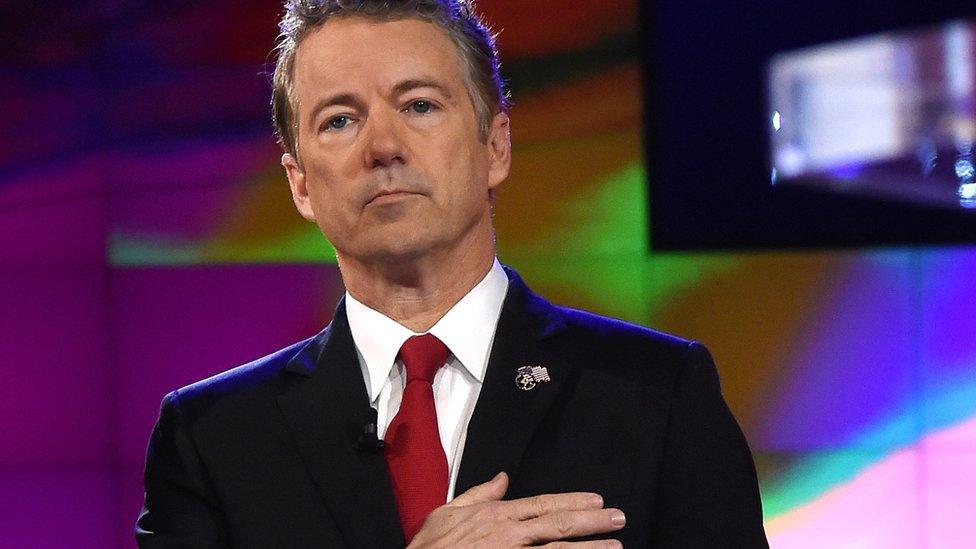

Will Rand Paul's debate presence change his waning presidential fortunes?

Rand Paul was thought by many to be a top contender for the Republican presidential nomination. He's not. What happened to the "libertarian moment" he was supposed to lead?

On a chilly Tuesday morning in Las Vegas, Nevada, Rand Paul addressed a crowd of about 50 supporters at his local campaign headquarters in a nondescript office park near the city's airport.

As he has during his entire eight-month campaign, he pitched himself as an outsider doing battle with what he calls the "Washington machine".

"On the left they're saying they want your guns," he said. "On the right they're saying they want your phone records. We need somebody to stand up to both the right and left."

Marcella Morrison, a heavily pierced young Nevadan, liked what she heard. The former Democrat is the type of new voter that many once thought would make Mr Paul a compelling candidate for the Republican nomination.

"Rand Paul is the only choice for me because everyone else on the Republican side, they are the embodiment of everything I hated about the Republican Party and why I was a Democrat for so long, blindly so," she said. "He's the only one with reason on either side."

The Paul campaign had hoped to find support among young voters

Mr Paul's campaign optimism was premised on the belief that he could broaden his party's appeal, hold on to voters attracted to the past insurgent presidential campaigns of his father, former congressman Ron Paul, and - thanks to his status as a US senator - peel off support from more traditional Republican constituencies.

For a while, it seemed like it might be Rand Paul's time to shine.

Just last year, a Time magazine cover labelled him, external "the most interesting man in politics".

Mr Paul appeared poised to capitalise on conservatives who chaffed at the growth of what they saw as an overly intrusive national security surveillance state and recoiled at the apparent militarisation and civil liberties abuses of local law enforcement.

Some on the right even heralded the arrival of a "libertarian moment", external, where the Republican Party would fully embrace a small-government agenda steeped in personal freedoms, with Mr Paul as its poster boy.

Storm clouds

When the first-term Kentucky senator announced his presidential bid in April, many political prognosticators viewed him as a top-tier challenger for the Republican nomination - maybe even the front-runner. Early polls supported such notions, showing Mr Paul at or near the top both nationally and in surveys of Iowa, which holds the key first-in-the-presidential-race caucus.

"With your help, this message will ring from coast to coast, a message of liberty, justice and personal responsibility," he said in his announcement speech, external. "Today begins the journey to take America back."

Mr Paul's views on foreign policy set him apart from his Republican rivals

Despite the fanfare, the challenges facing Mr Paul were apparent even on that morning in Louisville, Kentucky. A storm raged outside the hotel where Mr Paul held his campaign launch, and there were ominous rumblings from the nation's capital as well.

Although the candidate talked about expanding the Republican Party's base and running a different kind of campaign, the Washington foreign policy establishment was quickly moving to nip his White House aspirations in the bud. In an unprecedented move for so early in a primary campaign, an independent political group launched a million-dollar television advertising campaign calling Mr Paul's views on international affairs, which tend toward non-intervention, "wrong and dangerous". It was the first of what would be several adverts bashing the senator.

Since then Mr Paul has seen his fortunes in steady decline.

The Paris attacks in November and the shootings earlier this month have sharpened the focus of Republican primary voters on national security issues at the expense Mr Paul's civil liberties pitch, putting him more out-of-step with many of the party faithful he hoped to attract. When it was announced that Senate business would keep him from speaking at a Republican Jewish Coalition event in Washington, DC, several weeks ago, some members of the audience cheered.

His anti-establishment rhetoric has been drowned out by New York real-estate mogul Donald Trump's high-decibel campaign. And a fellow first-term senator, Ted Cruz of Texas, has drawn many of Mr Paul's Constitution-loving free-market supporters into a coalition with his evangelical Christian base.

Trumped by an outsider

Nevada was supposed to be fertile ground for Mr Paul's campaign. Four years ago, his father's supporters effectively took over the state's Republican Party apparatus. The western state's conservative voters place a high premium on personal liberty and look toward distant Washington, DC with unbridled suspicion.

"We know how the game is played," Carl Bunce, a Nevada businessman who was Ron Paul's 2012 state campaign chair and is now involved in Rand Paul's campaign, told the BBC. "It's going to happen again. Here in the state of Nevada we have a strong organisation."

Rand Paul's father Ron Paul (right) ran insurgent presidential campaigns in 2008 and 2012

This time around, however, there may be a bigger, brighter show in town.

The night before Mr Paul's modest Las Vegas rally, Donald Trump held a raucous event that drew thousands to a massive casino conference centre on the Las Vegas Strip. His supporters, many of whom are new to the political scene, see the New Yorker as a no-nonsense outsider who isn't beholden to either party's interests.

That was supposed to be Mr Paul's appeal.

Mr Trump's earlier appearance was on the mind of Gary Friedrich, another Paul supporter who came to see his candidate speak on Tuesday morning.

"Trump has how many years of media coverage if you add it all up?" said Friedrich, a retiree who has lived in Nevada for 40 years. "What's Rand got?"

He added that politics has become the new television sensationalist pornography, a game that Mr Trump is playing with unmatched skill.

Death watch delayed

As the final Republican debate of 2015 approached, Mr Paul's presidential bid was in a state of crisis. His campaign coffers, which never benefitted from the expected combination of grass-roots donations and support from billionaire donors, were nearly empty.

Based on his poll standing, it appeared likely that Mr Paul would be relegated to the undercard debate with also-rans like former New York Governor George Pataki and former Senator Rick Santorum.

Rumours swirled that Mr Paul was on the verge of dropping out of the race - fuelled by a cryptic response from the candidate that he'd make an announcement on the day of the debate if he did not qualify for the main stage.

In the end Mr Paul made the cut - or, rather, the rules were suspended by host network CNN to allow him to participate.

Mr Paul had several heated exchanges with Chris Christie during the last debate

During the debate, the Kentucky senator garnered more speaking time than he had in the four previous meetings. He sparred with Florida Senator Marco Rubio over legislation to curtail federal surveillance programmes. He clashed sharply with New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, who insisted he would enforce a no-fly zone that would target Russian planes in Syria.

Mr Paul quipped at one point that if US voters wanted a president who would start World War Three, "you have your candidate".

After the debate ended, Mr Paul's efforts were praised.

"It is inarguable the senator from Kentucky emerged as a key figure during the debate," wrote the New Republic's Jamil Smith, external.

Rand's perspective

Will Mr Paul's performance reboot his campaign? With less than two months until Republicans start heading to the polls to choose their nominee, however, his fate may already be sealed.

At a speech to the Las Vegas Economic Club the day after the debate, Mr Paul held out hope. He pointed out that polls can change, as witnessed by fellow candidate Ben Carson's recent precipitous collapse. He added that there are a large number of voters - possibly more than half - who have yet to fully make up their minds.

"There have been people with the exact same numbers as we have at the exact same time that have won Iowa," he said.

It seemed difficult for Mr Paul not to acknowledge the reality of his situation, however - a lower-tier candidate labouring on the trail with little media attention and virtually no momentum.

After a promising campaign launch, Mr Paul has struggled in the polls

"It's a gruelling thing to be away from the family so much," he said. "But it's a worthwhile project in the sense that I have a voice that's unique and distinct within either party. If it weren't for me in the debates, who would be pointing out the crazy idea of a no-fly zone?"

At the end of his speech an audience member asked Mr Paul why Trump supporters should back him instead of the brash New Yorker.

"I'm not crazy," he answered.

At this point, however, that may not be enough.