US election: Confessions of a four-time caucus correspondent

- Published

I went to my first Iowa caucus in 2004, which I realise makes me a novice by the standards of veterans of the American press corps, who can can wax informatively about the Dukakis campaign of 1988 or even Reagan's triumph in 1980.

But even those four cycles have given me some insight into what makes the Byzantine caucus process so compelling. In some ways Iowa is unique in the US presidential election process but it also represents a snapshot of the broader American mood.

Iowa is exciting, but more than that, it's inspiring. Residents of this large, mid-Western state give the most impressive display of democratic commitment I have ever come across in the West.

It is hard work caucusing and they take it very seriously here. They attend rallies, listen to speeches, put up with endless TV ads and then on a freezing winter's night they schlep through the snow to spend anything up to three or four hours casting a single vote.

I've even sat in a two-hour meeting where local residents were being instructed on how to caucus. They weren't even voting yet, but they still showed up.

The Iowa caucuses often attract intimate crowds in homey settings

It's also fun for us because it's one of the few times reporters are able to see the candidates up close. In return for their own diligence, Iowans expect the candidates to show up for intimate gatherings.

Admittedly at most of these "coffee shop" events I've been to, the ratio is something like this: reporters 54, residents 14, candidate 1. But at least you can elbow your way to the front of the pack and throw the candidate some random question. Senator this, governor that, why are you up in the polls? Why are you down in the polls? Why are you in the polls at all?

I see it as a test of my journalistic perseverance. These things don't change. Others do.

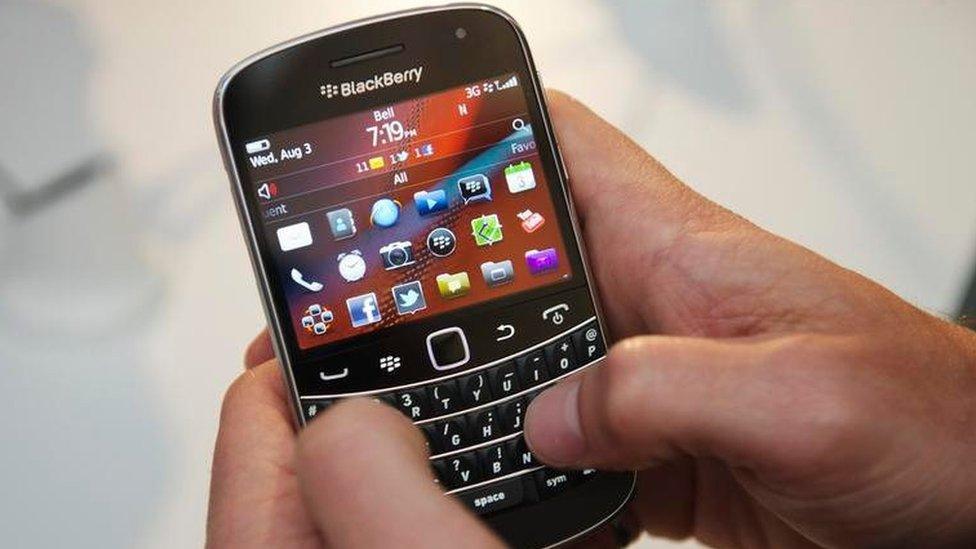

2004: Year of that little black box

2004 was the election of security moms. It was all about Iraq.

The night before the caucus in 2004 I remember going to a John Kerry rally in Des Moines.

I can't tell you much about what the candidate said because I was too captivated by the little black box ABC news anchor George Stephanopoulos was proudly showing me.

It had a tiny, tiny key board and with it he could send his editors emails from anywhere. Anywhere! Imagine that! He demonstrated. I wondered why it was called a Blackberry and felt sure the name would never catch on. It had nothing to do with fruit. I should have thought of Apple.

I don't think I missed much though, ogling George's new toy rather than listening to the esteemed senator from Massachusetts. His speech was really no different from the one I'd heard him give many times before. The supporters were the same crowd too. Angry at President Bush, angry at the war, desperate for a Democrat who could bring American troops home.

As I watched them in a school gym that night haggle and argue to get warm bodies into their camp (a colleague once described the Iowa caucus as a very political cocktail party, without the cocktails,) it all felt rather downbeat. Perhaps it was clear even to them that Kerry was an imperfect messenger. He was jumbled on the one single issue that mattered that year.

By the end of his campaign I still couldn't really tell you what his position on Iraq was, and if I, whose job it was to follow the election news every day, couldn't understand it, how on earth could, the average voter.

2008: Return to sanity

2008 brought us change. And change too for Iowa. A very white state voted for a black man with a foreign sounding name. That year the Democratic caucus-goers looked and sounded different.

Four years earlier I had found them a rather beleaguered bunch - promoting a candidate many of them knew wasn't very impressive.

In 2008 they were just as undiverse as they'd ever been, but they were energised, thrilled by both Obama and Clinton. It was their race, their time and they were going to change the world after eight years of Bush.

It's sometimes hard to remember now that the blush has worn off the Obama rose, now that so many of the promises proved impossible to keep, but those days in Iowa in 2008 were heady indeed.

And my editors in London were as excited as the crowds in Sioux City. They couldn't get enough of this contest between the first black man and the first woman. That was the caucus at which Europeans seemed to feel America was returning to sanity.

The 2008 Democratic race was notable for being a contest between the first black man and first woman

And it was in Iowa in 2008 that I finally grasped a fundamental difference between Americans and Europeans.

It was thanks to a union worker I interviewed outside a tyre factory north of Des Moines. Times were hard for this gentleman. His daughter had cancer, his wages were low and he had trouble with his health insurance. But he was canvassing support for the other democrat, John Edwards, a multi-millionaire who had reportedly just got a $400 hair cut on a private plane.

I asked this man whether that didn't make him mad. Here he was with so little and his candidate had just got a gold-plated trim. Of course not, he replied, it's great that John is rich, it's what we all want.

European's scepticism, even jealousy, of self-made wealth eluded him.

Of course 2008 was an open race on both sides. And we had fun chasing little-known hopefuls from small town to smaller village (remember Alan Keyes? No, nor do I).

We hadn't yet been introduced to Sarah Palin and somehow the larger-than-life characters on the Democratic race sucked most of the oxygen out of the press coverage. I do remember John McCain larking around for my camera, it was the days before he bitterly turned against the media.

2012: Wasted GOP opportunity?

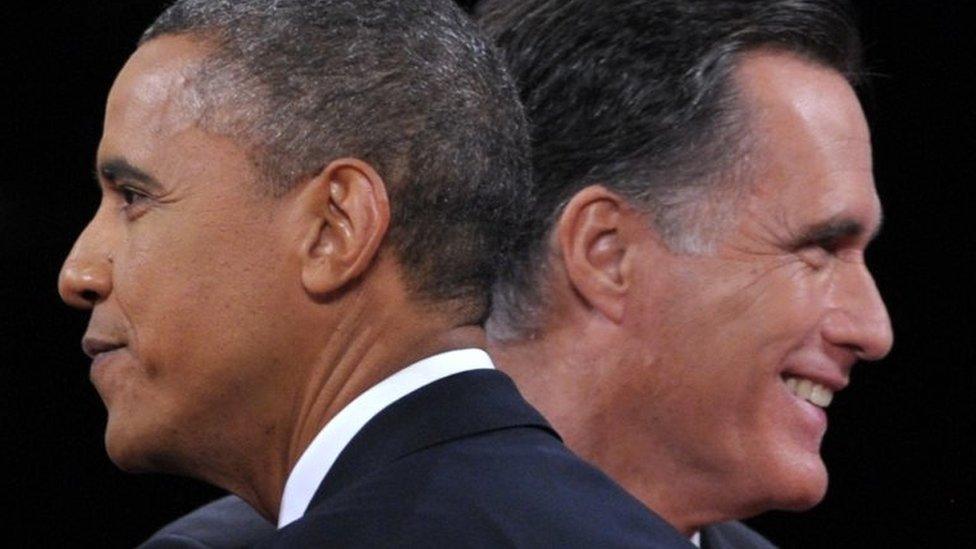

In 2012 all the focus switched entirely to the Republicans and the question was would Mitt Romney, a Mormon, win the hearts of Iowa's evangelicals?

Or would they gravitate more to Rick Santorum and Michele Bachman - two proven Christian conservatives, one of whom, by the way is running again this year. Some faces don't change.

It always slightly surprises me that in a country of more than 300 million people it's so hard for the parties to find a first-rate candidate.

Kerry was a weak candidate in 2004. Romney was a weak candidate in 2012. In both those elections the parties had a good chance of winning. In 2004 because of the Iraq war and in 2012 because of the recession.

Republican hopeful Mitt Romney failed to muster enough support to take the presidency from the Barack Obama in 2012

From Iowa of '12 I remember a disagreement with my editor in London. That night I said on air that the Republicans had a good chance of winning that election because the economy was so bad. He couldn't really believe it.

In retrospect he was still steeped in the European affection for Barack Obama. I was hearing America's loud disgruntlement. In the end Republicans didn't win. But I still believe they could have done, with a stronger nominee.

All of which brings us to Iowa 2016 and a political show none of us anticipated, on either side of the race. This year, a state deeply wedded to its political traditions has thrown the rule book into the snow.

Donald Trump appeared to be everything Iowa isn't: brash, flashy, rude and yet they love him. Even when he committed the cardinal sin of telling Iowa voters they were stupid, his poll numbers went up.

None of us who have covered American politics for a while expected to see anything like this. It's exactly why we keep coming back.

For the last couple of cycles I've thought, that's it, I'm done. It's too cold, too far, Iowa gets too much attention anyway.

And yet here I am back again. I wouldn't miss this one for the world.

- Published28 January 2016

- Published16 March 2016

- Published19 January 2016