The crisis of US governability

- Published

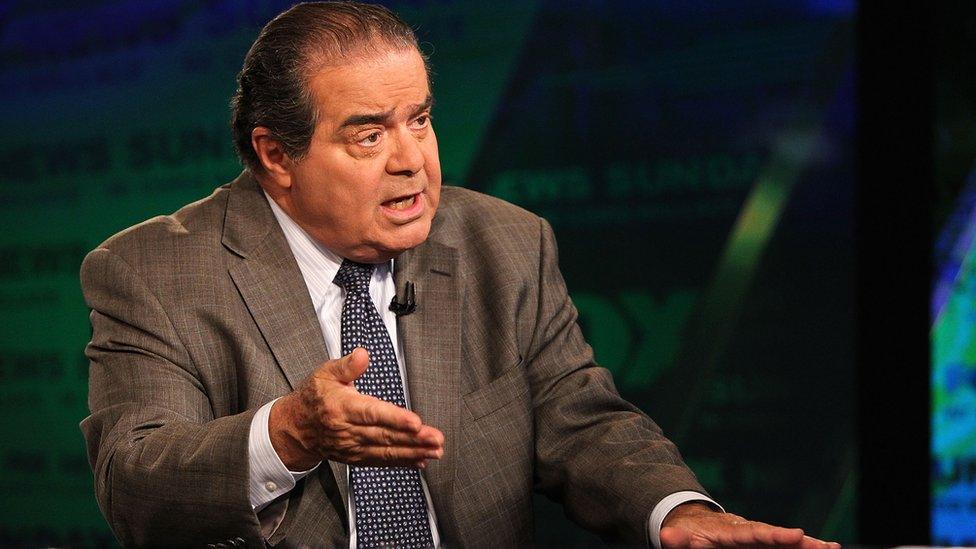

Justice Scalia's death has pushed Washington politics into overdrive

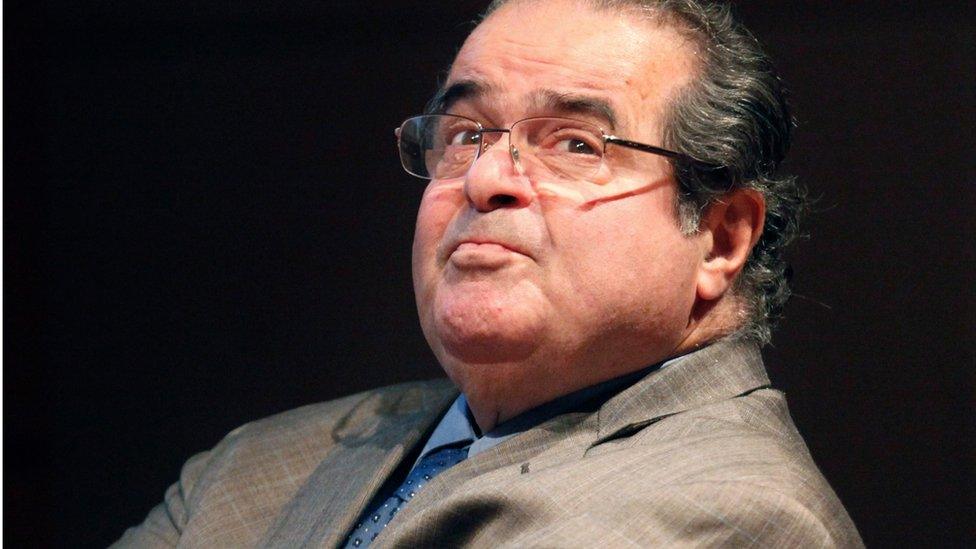

As a case study in Washington dysfunction, the battle over who should fill the vacancy on the Supreme Court left by the death of Antonin Scalia is hard to better.

It brings into collision the three branches of the US government, the executive, the legislative and the judicial. It exposes the extreme partisanship that has become the hallmark of Washington politics.

And it does all this in an election year - when both the presidency and the Senate are up for grabs - which means the next eight months could become a civics lesson from hell, to borrow the phrase used by the historian Louis Menand to describe the disputed aftermath of the 2000 presidential election.

The brief moment of remembrance for Scalia, an intellectual colossus treated with almost Reagan-esque reverence on the American right, was quickly overtaken by partisan rancour.

'Delay, delay, delay'

Within minutes of the news breaking, Conn Carroll, the communications director for the Republican Senator Mike Lee, asked on Twitter:, external "What is less than zero? The chances of Obama successfully appointing a Supreme Court Justice to replace Scalia?"

Within a couple of hours, the Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell delivered a more decorous, if no less pointed, version of that tweet, when he stated that the Senate should not select a replacement until a new president is sworn in, even though inauguration day is still 11 months away.

Later that night, in a televised Republican debate in South Carolina, Donald Trump summarised this stance in a three-word slogan: "Delay, delay, delay." The backlash from Democrats was predictably vituperative.

Given there is no historical precedent for leaving a seat on the Supreme Court vacant during an election year, the talk inevitably is of a constitutional crisis. But what we are primarily dealing with here is a crisis of governability that predates the death of Antonin Scalia. His passing has merely brought this dysfunction into sharper focus.

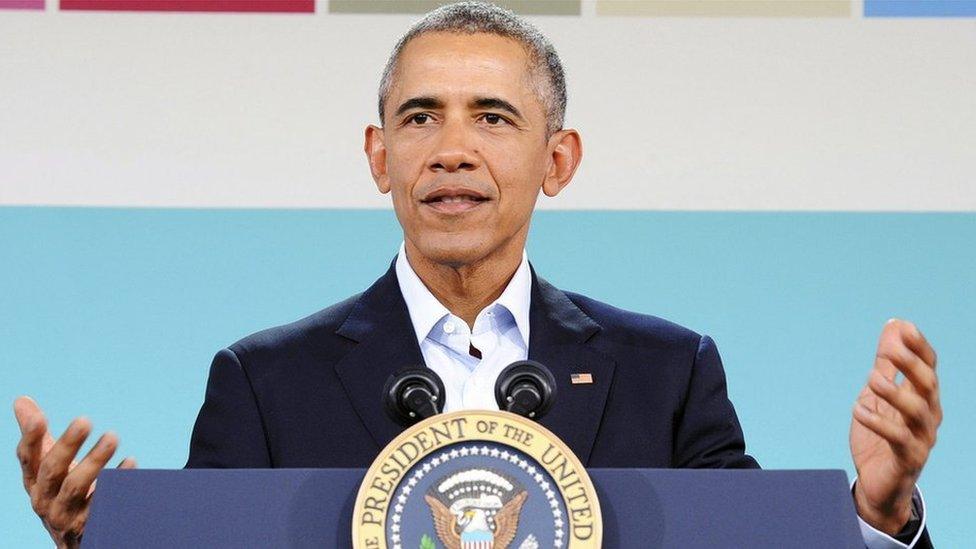

President Obama is expected to nominate a new justice in the coming weeks

In modern-day Washington, gridlock has become the norm.

Obstructionist tools like the filibuster, which were once used sparingly, have become routine (a supermajority of 60 votes is required to pass contentious bills rather than a simple majority, a number that is notoriously hard to get).

Brinkmanship has replaced sensible negotiation, as evidenced by long-running disputes over the budget and the raising of the debt ceiling.

Bipartisanship has been likened to "date rape", the phrase first used by the former Republican House leader Dick Armey. Small wonder that the former Republican House Speaker John Boehner was forced to conduct negotiations with Barack Obama in secret, lest the Republican Caucus accuse him of betrayal.

'Worst ever'

The 113th Congress, in which the Democrats held a majority in the Senate and the Republicans controlled the House, is widely regarded as among the worst ever.

Sitting from January 2013 to January 2015, it passed just 234 bills, which sounds like a creditable number until you compare it with the infamous 'Do nothing" congress which Harry S Truman railed against in the late 1940s, which passed more than 900.

It shut down the government for 16 days in 2013, and recorded a record low average approval rating of just 14%.

The ability of the president and congress to deal with major issues, most notably the colossal size of the federal debt, has been seriously impaired.

"Congress has been less productive in legislation, more prone to delays in appropriating funds, and increasingly slow in handling executive and judicial appointments," concluded Prof Nolan McCarty, part of a task force appointed by the American Political Science Association to study governmental dysfunction.

The White House "bemoans Republican obstructionism"

At this basic operational level, Washington is failing. Republicans complain that President Obama is running the country using monarch-like executive powers that go beyond his constitutional authority.

The White House bemoans Republican obstructionism on Capitol Hill, which, it argues, leaves the president with no choice but to circumvent congress.

"Crisis point" is how two of Washington's most experienced retired lawmakers, Trent Lott, the former Republican Senate majority leader, and Tom Daschle, his opposite number on the Democratic side of the aisle, have described it.

Joining forces to write a scorching polemic, Crisis point: Why we must - and how we can - overcome our broken politics in Washington and across America, they note: "Bipartisanship is the life force that keeps the government running. It is neither a life raft to be embraced only in crisis, nor a naive idealism to be mocked.

"Bipartisan negotiation is the pumping blood of democracy, and it has run dry in the current Washington landscape."

Trent Lott and Tom Daschle tell the BBC's Katty Kay "we all have a burden to bear" in making the government work

Lott and Daschle, it should be remembered, were hard-nosed political warriors, but patriots as well as partisans.

They are far from alone in penning despondent tomes about deadlocked Washington.

Consider the most recent books from Thomas Mann and Norm Ornstein, two of America's most respected political scholars.

In 2006, they brought out, The broken branch: How Congress is failing America and how to get it back on track. By 2012, they thought it necessary to bring out an updated study, with an even gloomier title - It's even worse than it looks: How the American constitutional system collided with the new politics of extremism.

One wonders what title they will come up with next.

Perils of partisanship

What explains this dysfunction? A central reason, obviously, is the polarisation of politics, which in Congress reached a record high in 2013, according to studies of lawmakers' voting records reaching back to the late 19th Century.

No Senate Republican was more liberal than a Senate Democrat and no Senate Democrat was more conservative than a Senate Republican. This might seem like a statement of the obvious given the modern-day partisan divide, but it is historically new.

In 1994, there were 34 senators who occupied this political centre ground, what's often referred to as the ideological overlap.

In 2013 Congress shut down the government for 16 days

Political moderates like Sam Nunn, the former Democratic Senator from Georgia and Richard Lugar, a Republican from Indiana, have become increasingly rare, their places often taken by fierce partisans.

Moderates, like Lugar, tend to be punished for reaching out across the aisle. He was ousted in 2012, for instance, following a Tea Party challenge in the Republican primary.

The threat of a primary challenge from a rival within the party often poses more of a threat than being ousted by a candidate from the opposing party in the election proper. This is especially true in the House of Representatives where only a small number of seats, about 16 out of 435, are a genuine toss-up between the two parties. This encourages hyper-partisanship and militates against compromise.

It's the combination of extreme partisanship and the US Constitution that turns a problem into a crisis.

The founding fathers designed the constitution with checks and balances to ensure a separation of powers between the three branches. But these checks and balances can easily be used as partisan weapons.

More paralysis and stalemate?

For the system with so many veto points to work, it needs co-operation and compromise. Lyndon Johnson's landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act, which dismantled segregation in the south, required Republican support to overcome a filibuster from southern Democrats.

Ronald Reagan and the former Democratic House Speaker Tip O'Neil - though fiercely opposed ideologically - shared a commitment to get things done, which helped them put social security on a surer footing and bring about tax reforms.

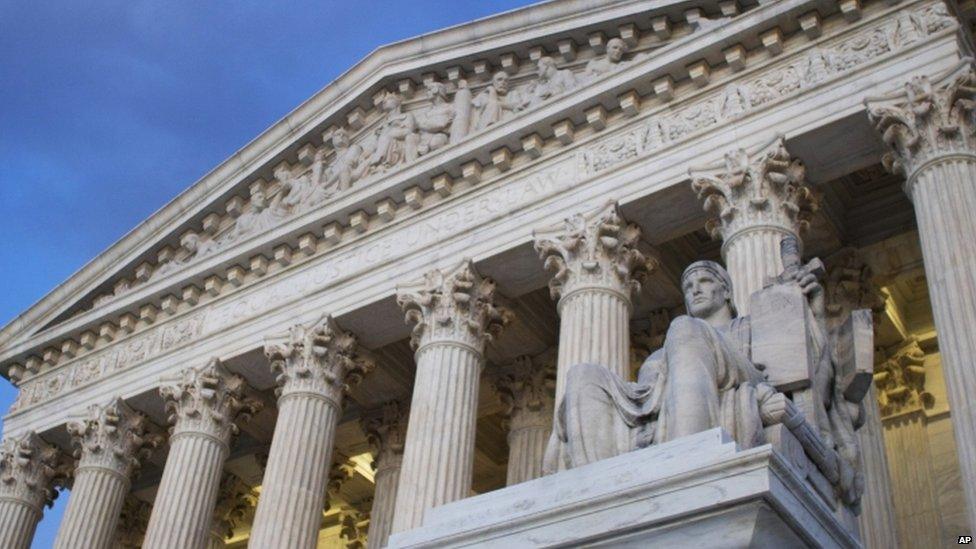

The Supreme Court has at times functioned with fewer than nine justices

Even Newt Gingrich and Bill Clinton reached agreement on a balanced budget and welfare reforms.

This kind of compromise is all but absent in modern-day Washington, save for a few issues such as trade promotion. And both sides have used their constitutional veto powers to thwart the other.

The kind of ideological battles exposed by the death of Antonin Scalia are nothing new, though this one is particularly charged because it could turn the Supreme Court into a left-leaning branch of government rather than the present right-leaning one.

Nor are constitutional wrangles unprecedented. But the looming battle could take Washington's trench warfare to a new level, producing more paralysis and stalemate.

- Published17 February 2016

- Published16 February 2016

- Published14 February 2016

- Published8 February 2024