Returning to an Ohio town on the decline

- Published

An overgrown parking lot in front of the closed Packard Electric complex in Warren, Ohio

America is in the middle of its most volatile presidential election season in half a century - and the Midwestern state of Ohio is set to be a key decider in the race. London-based American writer and broadcaster Michael Goldfarb returns to the state he first reported on two decades ago to see how much has changed.

If you've done any travelling at all you will know this experience.

You arrive in a small town on your way to somewhere else. The place looks interesting but you can only stay long enough for the townscape to worm its way into your memory. You kick yourself from time to time that you didn't spend longer there and realise, as the years pass, you will never get a chance to go back.

Ripley, Ohio, was one of those places for me - a lovely town on the majestic Ohio river. Twenty-three years ago I passed through while making a series about the US Midwest for the BBC.

But recently, I had a chance to return. I had been driving around Ohio reporting on the upcoming presidential election. I had been in towns and cities still reeling from the last 40 years of social and economic change in America, places like Toledo and Cleveland and Akron.

By the banks of the Ohio River

The journey had depressed me to no end, and now I had one more day before flying back to London. I was just a two-hour drive from Ripley. I headed south on US 68.

It was a glorious autumn day, all those years ago when I first visited. I had driven south to the river on the same road through fields harvested and turned over for the winter. Tobacco was a big crop near Ripley and in the barns the giant leaves were hung upside down to dry out.

The town's Main Street ends at the river and in the block before the great waterway was a cafe and pool hall.

There were tables crammed with farmers, workers - the whole male population of the town it seemed - shooting pool, playing cards, killing time. Big open windows letting the light stream in. It was a world entirely different to mine. I lingered long enough for a cup of coffee but then had to move on.

Now I was going back to ask those folks or their children what they thought about the changes of the last few decades.

A cracked window in Ripley, Ohio

It was a glorious late spring day when I finally returned. I drove south towards the river. Some of the farm communities have become suburbs. I didn't see much tobacco growing, but the corn was already green and thigh-high.

I pulled into Ripley and found the pool hall. It was out of business, and had been for some time. Almost all the store fronts on the block were empty.

One more wrecked community in Ohio. I don't know why I expected anything else.

Bruce Springsteen recorded the song My Hometown more than 30 years ago. It is based on what was happening in the place he grew up - Freehold, New Jersey.

"Foreman says these jobs are going, boys/ and they ain't comin' back to your hometown."

The mixed economy that sustained a well-paid, secure working class with wide opportunity for upward mobility was disintegrating with those jobs, not just in Springsteen's hometown but all over the country.

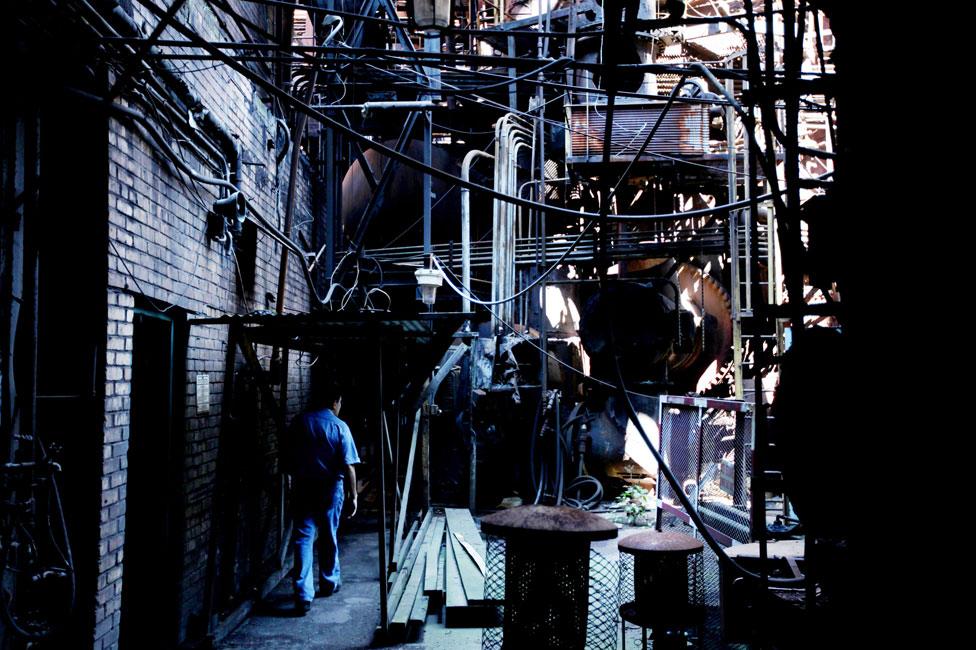

Ohio is covered with the remains of that era. Old industrial buildings crumbling by the side of interstate highways can seem as picturesque as ghost town buildings in a Hollywood Western. Freighters that worked the Great Lakes lie rusting at anchor in places like Huron.

But they are not just symbols of the past. The world of employment they represented has yet to be recreated three-and-a-half decades later.

More from the BBC

The anxiety that accompanies economic uncertainty is shaping this year's presidential contest.

In Ohio, a universal opinion, among voters I spoke to, is they don't like the choices on offer.

The Democratic party candidate, Hillary Clinton, is almost too well known.

"There could be a better woman being the first president of the United States," Alexis Altvader, training to be a nurse, tells me.

"It's easy to back a woman, but it's hard when you don't believe in the same things she does."

Her boyfriend, Josh Corbin, a conservative Republican by inclination and family tradition, is not thrilled by Donald Trump.

"This election season with the way it's been so chaotic, a lot of people kind of started pushing the notion of never Trump, never Hillary," Corbin says.

He will probably vote for the Libertarian Party candidate, although he worries that in a critical swing state like Ohio, which has picked the winner in every election for 50 years, a vote for the Libertarians, who have no chance of winning nationwide, will help Clinton take the state and the presidency.

We were speaking at Young's Jersey Dairy in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Young's is an institution in south-west Ohio.

A working dairy farm, it is also a pleasure dome. The owners started making ice cream and selling donuts nearly 50 years ago. Today you can play miniature golf, and eat salty caramel pretzel crunch ice cream.

Young's is a great example of local American entrepreneurialism. But America has changed. Yellow Springs was completely rural 40 years ago. Today the suburbs of Dayton stretch almost to the farm's front door.

"Now Main Street's white washed windows and vacant stores"

The daily life of Ohio happens in the suburbs. Near Dayton, I went to the latest in retail shopping experiences: The Greene. The era of shopping malls with 50 stores under one roof is over.

An abandoned Ohio shopping mall from the "Black Friday" series by Seph Lawless

The Greene is designed like a Disneyland version of small-town America. But each store front has a high end shop in it.

The Greene is situated just off the motorway south-east of Dayton. But the downtown of this once-great industrial city, the place where the Wright brothers designed and built the first plane, is pretty much empty except along a half-kilometre stretch of 5th Street.

There are some old buildings not yet turned into parking lots, buildings that seem to be the model for the buildings at the Greene. These have been converted to restaurants and bars with music. Perfectly charming.

But the big money investment of the private sector goes to places like the Greene. And Americans seem to like it that way.

Listen to more

Listen to Michael Goldfarb's radio documentary, America's Independent Voters, on BBC World Service's The Documentary at 17:06 on Saturday 2 July, or catch up later on the BBC iPlayer.

The problem with suburban life is that there is no social centre to it. It's all about dipping in and out, being isolated in your car.

In Ripley, most of the town's life seemed to be lived on that one block of Main Street with a pool hall. I could have lingered there for hours.

I went to the Westgate Mall in suburban Toledo, Ohio. The city's downtown contains acres of empty parking lots, while the Westgate is surrounded by traffic. I stopped into a Starbucks. People were in and out in a hurry. There was nothing there that made me want to linger except the free WiFi.

Suburban life also allows people to ignore the social problems of their society. In Ohio, these mirror the physical decline of Ohio's former industrial heartlands. There are 20 people a week dying of heroin overdoses in this state, external. Life expectancy among less-educated white people is declining. Many of the old industrial towns and cities now have had three generations of residents without full-time employment.

"Last night me and Kate we laid in bed/talking about getting out/Packing up our bags maybe heading south"

When Springsteen recorded the song a great migration was under way from the industrial heartlands of America like Ohio to the South and South-west.

That was the American way - hard times in your hometown? Move to somewhere else. There is always work.

The "Rust Belt" is the nickname for a string of cities which once hosted a thriving manufacturing sector

Today, employment is so insecure people don't leave jobs even when they are unhappy with their work. They can't be sure they will find another. Fluidity - movement between jobs - is down 15 %, external. So people feel trapped.

How many of them are there? How much is their despair responsible for the unlikely candidacy of Donald Trump? How much of that trapped feeling do they blame on Hillary Clinton, an advocate of the free trade deals that led to many factories in Ohio shutting down?

I had hoped to talk to people in Ripley, Ohio, about that, but the pool hall was long gone, the town listless and empty.

It will be November before there is an answer.

More from Michael Goldfarb: The 40-year hurt

"When I am asked to explain the Trump phenomenon on BBC radio and television, I know I don't have to teach this history. I have to stay focused on the day's events and explain a bit about the vagaries of the primary process. I have to bullet-point data: the polls, the employment figures, the wage stagnation. I have to throw the story forward because incredulous presenters end each interview by asking, 'But can Trump win?'

"And I think to myself there is no way to explain in a brief interview the power of the 40-year hurt in shaping American society. There is no number or data set that can measure its pain."

- Published26 March 2016

- Published24 January 2016

- Published8 April 2013