US election: What happens if Donald Trump loses?

- Published

One man has made this year's US presidential election the most extraordinary ever.

It has been an electric slugfest, democracy at its most vibrant and shameful.

More mud has been flung around than is churned up in that quintessential American sport of big trucks with big tyres screeching through the Georgia mud pits.

This was Donald Trump's election, even if he loses. Particularly if he loses.

The forces he has unleashed and validated won't go away. He is an incarnation of a mood, which has become a movement.

The really startling thing about Donald Trump is not how exceptional he is, but how much he is part of an American mainstream.

This bitter battle won't end on election day

The state that defines the race

America's coal country feels forgotten

Predict the president - play our game

Those who made headlines a few days ago, external, threatening bloody revolution and a march on Washington if Hillary Clinton wins, can be ignored.

But what they shout tells you something about the mood of their milder fellow Trumpists.

The adage that a win by a single vote is a win, is only partly true.

Battles are won and lost. Wars rage for years. In the UK, "Brexit means Brexit" has been used to encourage defeated Remainers to slink away and shut up.

Vanquished Americans, overflowing with a sense of injustice and anger, won't go so quietly.

If Mr Trump loses, he may stick around complaining, issuing legal challenges and dire warnings.

He might set up Trump clubs across America to further his cause, or fund a TV station.

But even if he disappears with uncharacteristic humility, he would leave a legacy that could transform American politics.

However, his fundamental attack against an elite doing down the common folk isn't new.

Back in 1891, the People's Party, external argued for the "plain people" against the "controlling influences" dominating the political mainstream, and demanded the expulsion of Chinese workers.

If you read no other political book this year, read The Populist Explosion by John B Judis, external, which brilliantly sets out the connection to present circumstances.

The 1964 Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater campaigned against civil rights, opposed his party's liberal elite and argued that "extremism in the defence of liberty is no vice". He lost, but helped transform his party.

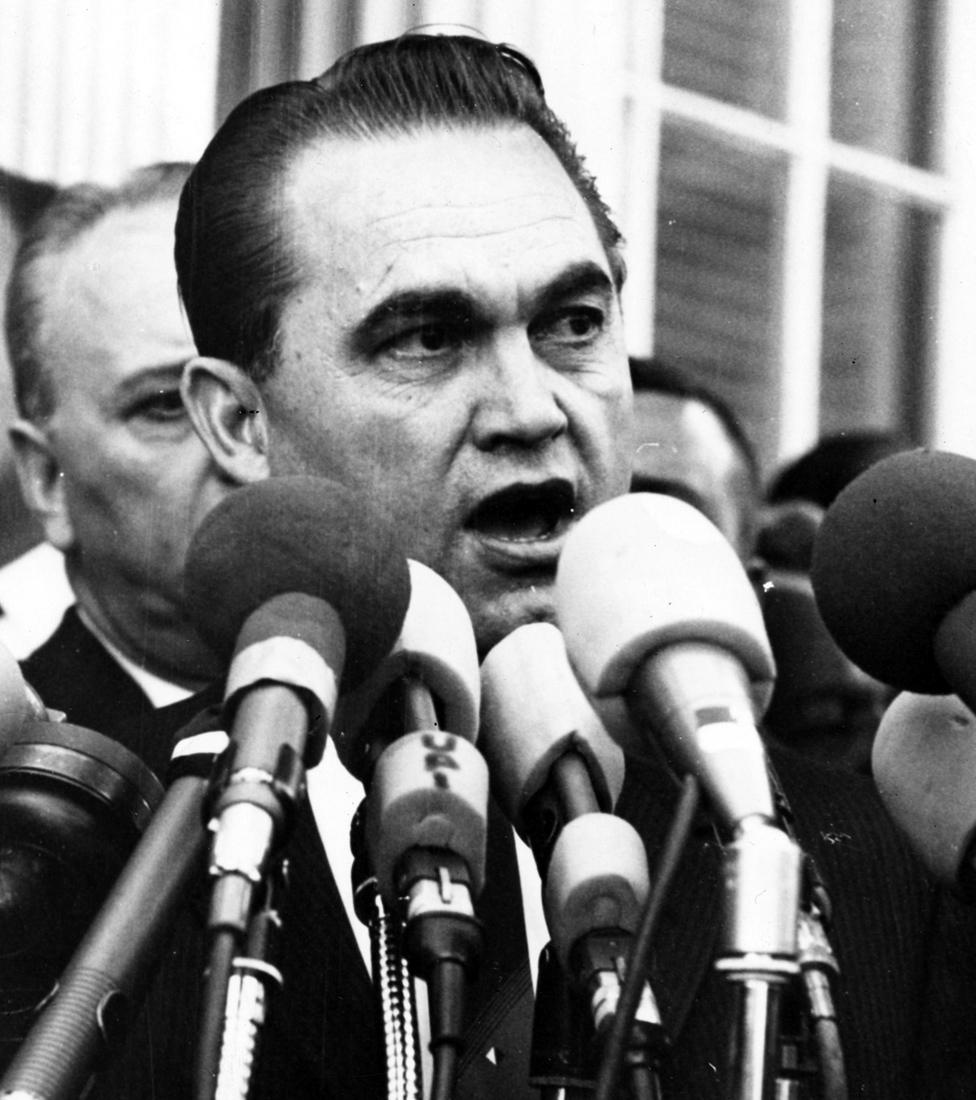

Four-time presidential candidate George Wallace famously called for "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever".

But more modern right-wing populism in America may have begun with ex-Democrat George Wallace, who campaigned as an independent in 1968.

His case was based on a ferocious defence of the continued segregation of black and white, combined with an economic appeal to white blue-collar workers.

"There's a backlash in this country against big government," he said. "If the politicians get in the way, a lot of them are going to get run over by this average man in the street: this man in the textile mill, the man in the steel mill."

He lost, but his supporters didn't go away. And those workers in the textile and steel mills saw their standard of living and social position decline.

Pat Buchanan failed to win the Republican presidential nomination but influenced the party

For years, Pat Buchanan - who tried to get on the Republican ticket a couple of times but ended up running for president for the Reform Party in 2000 - attacked not only transnational corporations and global competition, but also trade deals that benefited Mexican workers.

Sound familiar? By then, those steel and textile mills were closing down and many of those workers worked no longer. Mr Buchanan lost, but many listened.

Supporters and movements morphed and overlapped. The evangelical Christian right waxed and waned.

After Barack Obama's election, the Tea Party built a movement that combined several different resentments about bank bailouts, taxation and big government.

Former Alaska Governor and leading Tea Party figure Sarah Palin was idolised by some disaffected Republicans

Mr Trump has put these concerns centre stage for the Republican Party, linking opposition to global free trade and widespread immigration to white unease at a black president and minorities' growing status and power.

Textiles and steel still resonate in the imagination and the children of those workers who lost their jobs struggle. But that's not all.

Many middle-class Americans on fair wages are burdened with huge college fees, face big medical bills all their life, and risk an insecure old age.

Life doesn't feel like it's getting better and better for many.

Add to the brew fears of a changing America, and the belief their taxes go only to help the feckless and illegal immigrants.

Donald Trump has campaigned extensively across the US's so-called rust belt

Mr Trump's appeal is directly to these people. The sharp intake of breath at the vulgarian on the high wire disguises the strength and breadth of this feeling.

Donald Trump is an American archetype, the huckster, the booster, the snake oil salesman.

What many forget in their liberal disgust is that in the old Wild West many bought the snake oil off the side of the wagon. When you've tried every other remedy, why not give it a shot? What's the risk? Similarly in politics.

This is not just the territory of the right.

President Clinton II would face similar rumblings to her left.

The sort of people who support Occupy and Bernie Sanders may hate Mr Trump, but they agree with his excoriation of the establishment, and his assault on the arrogance of the rich and powerful.

They will agree that the US risks a third world war if Mrs Clinton steps up military action in the Middle East and confronts Russia.

Hillary Clinton's foreign policy is unpopular with many Democrat Party supporters as well as Trump fans

This may not daunt her. But if she wins, her legitimacy will already have been undermined by the accusation that she succeeded only because she was the candidate who was not Donald Trump.

The Republican Party would find itself with a heightened dilemma that so far it has ducked and ducked again.

In the UK, the day after the election, the losing party has a stark choice - to ditch or support its defeated leader.

There are not just debates, but votes about where they went wrong. Too left or too right - too much of this policy, too little of that?

In the US, it isn't quite so frantic.

The Republicans won't be choosing a new presidential candidate until 2020, and no-one can guess now who it will be.

Before I became the BBC's North America editor, I asked a host of diplomats, politicians and journalists who would face Mr Obama in 2012. No-one said: "Mitt Romney". Not a single commentator dreamt it would be Mr Trump in 2016.

So the Republicans have time. But eventually they will have to make a decision. It is not just about embracing a populist rhetoric. Many do that already. Trump was just better at it.

They have to decide whether to adopt the policies that go with a conservative rejection of globalism and economic liberalism, which would horrify their remaining supporters in Wall Street and big business.

But if they don't, although the two-party system in America is immensely durable, it is possible that an inchoate angry movement could spill outside its boundaries, flowing who knows where.

The pitfalls are plain. The conservative political establishment's approach to the Tea Party was an idiot's guide on how not to do it.

Partly because of the system of primary elections - which allowed the "deselection" of moderate candidates - the party was all but taken over by radicals who then became the mainstream.

There was a seemingly endless contest of candidates pushed into a Dutch auction, outbidding each other in outrage, moving further to the right.

There seemed to be no thought given to building an electoral strategy beyond the activist base, or to forming an alliance with the less militant, let alone figuring out how to turn ideologically driven anger into a coherent policy platform.

Mr Trump has made this problem more acute by making it appear like a sustainable strategy.

It may not matter for a good while - simply saying: "No, no, no," to the Clinton White House would do for a bit.

But there is little glory in becoming the eternal outraged opposition, shorn of serious ideas about how to exercise power.