What will Trump's foreign policy look like?

- Published

So what now? The election of Donald Trump presents Britain with many challenges and some opportunities.

The president-elect is the son of a Scot, he owns property and golf courses north of the border, and says nice things about Britain when he visits. "Britain's been a great ally," he said in May. "With me, they'll always be treated fantastically."

He supports Brexit and makes positive noises about Britain securing a trade deal with the US. He said: "I'm not going to say front of the queue, but it wouldn't make any difference to me whether they were in the EU or not. You would certainly not be back of the queue, that I can tell you."

Mr Trump has also shown himself eminently flexible on policy, a point that former President Jimmy Carter made to me when he visited Britain earlier this year. This means that in some areas of international policy there will be opportunities for the UK to engage and to influence.

So there will be something for British diplomats to work with. And, of course, the longstanding intelligence, military and diplomatic relationships between Britain and the US will endure, regardless.

And yet the challenges are huge. There are many policies that Donald Trump supports that Britain opposes.

Mr Trump has called Russia's President Putin "a hero"

He wants to tear up the deal constraining Iran's nuclear ambitions that the UK worked so hard to secure. He wants to withdraw from the Paris climate change deal. He wants to tear up some of America's free trade agreements and instinctively leans towards protectionism.

He wants to shift the focus in Syria towards fighting the Islamic State group, rather than seeking a political end to the civil war without President Bashar al-Assad. He wants to engage with President Vladimir Putin of Russia - whom he describes as "a hero" - rather than confront a leader that many in the West see as a growing threat.

And above all he has said that America's allies in Europe and Asia must do more to pay for and provide for their own defence, even suggesting that the US might not come to the aid of a Nato country if it fails to pay its bills. This will worry the Baltic states no end.

Those are what another Donald, Donald Rumsfeld, might describe as the known knowns. But it is the unknown unknowns that worry diplomats just as much.

Could a Trump presidency see the ending of the Pax Americana?

"He is an unknown quantity," said one. "No-one knows what he is going to do." They say Mr Trump's advisers make a distinction between what they call "campaign talk" and actual policy. "They don't recognise campaign rhetoric and promises as something they feel bound by," another official said.

So there will be an unpredictability to the Trump White House that will worry Western leaders. But more than that, there is also the sense that his focus will be on America's domestic problems rather than its interests overseas.

"Americanism, not globalism, will be our credo," Mr Trump said as he accepted his nomination at the start of the contest. Diplomats say this means the president-elect does not believe in the Pax Americana, the idea that an internationalist United States at least tries to make the world a better place.

Instead, they say he sees foreign policy as transactional, a process of improvised ad-hoc deals rather than the projection of US values and interests. Mr Trump's slogan was: "America first," they point out, and he means it.

The most pessimistic diplomats talk about a fracturing of the post-War international consensus. They dismiss comparisons with Ronald Reagan, saying the former president had governed a major state, that he inspired rather than galvanised, that he unified rather divided.

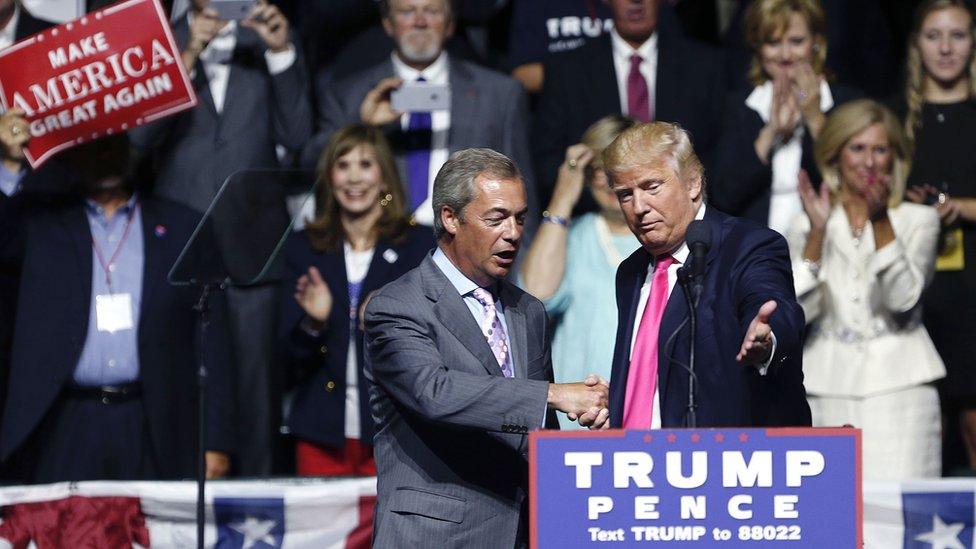

Nigel Farage has said he might enjoy being Mr Trump's ambassador to the EU

Much will depend on whom Mr Trump appoints as his secretary of state.

Names in the frame include:

senator Jeff Sessions, of Alabama, who is heading up the Trump national security transition team

John Bolton, the former US ambassador to the UN

Richard Haas, head of an influential foreign policy think tank in Washington

Stephen Hadley, a former national security advisory to the first President Bush

And of course, there is always the possibility that Nigel Farage might find a role in the new administration - he has modestly suggested he might enjoy being Mr Trump's ambassador to the EU.

The fear among some Western diplomats is that the Trump election will not only provide a vacuum in which other countries can expand their global influence - such as Russia and China - but at the same time encourage other populist, anti-establishment politicians across Europe and the world.

The Italian prime minister is facing a real threat in a constitutional referendum next month. The Netherlands, France and Germany are braced for tricky elections next year.

One senior diplomat told me: "What does this mean for Marine Le Pen?" - a reference to the far-right party leader in France. Little wonder she was one of the first foreign politicians to congratulate Mr Trump.

Theresa May said that Mr Trump's view that Muslims should be banned from the US was "divisive, unhelpful and wrong"

As if all this was not enough of a challenge, some UK policymakers have a few bridges to repair with the Trump administration. In January, MPs from all sides of the House of Commons lined up to attack the president-elect as they debated a motion to ban him from travelling to the UK.

Last year, the Prime Minister, Theresa May, said Mr Trump's promise to ban Muslims from the US was "divisive, unhelpful and wrong", it was "nonsense" to suggest there were no-go areas in London, and he did "not understand the UK and what happens in the UK".

Inevitably, the Foreign Secretary, Boris Johnson, went even further. He said: "Donald Trump's ill-informed comments are complete and utter nonsense. Crime has been falling steadily in both London and New York - and the only reason I wouldn't go to some parts of New York is the real risk of meeting Donald Trump."

And this year in May, before he became Foreign Secretary, Mr Johnson broke the cardinal rule of not intervening in another country's election. "I am genuinely worried that he could become president," he said. "I was in New York and some photographers were trying to take a picture of me, and a girl walked down the pavement towards me and she stopped and she said, 'Gee is that Trump?' It was one of the worst moments."

So some humble pie will have to be eaten, and the special relationship is going to be tested as perhaps never before.