Obituary: Richard Attenborough

- Published

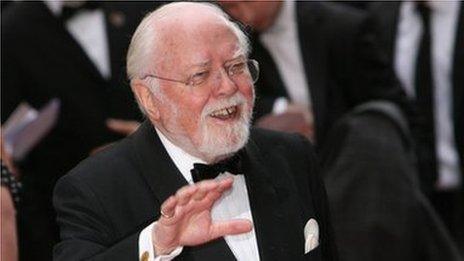

Much of Attenborough's work reflected his political beliefs

During a career spanning 60 years, the irrepressible Richard Attenborough became one of Britain's best-known actors and directors: a man of charm, talent and old-fashioned liberal principles.

What one writer described as "an apparently unquenchable appetite for doing good", Attenborough himself attributed to his upbringing in Leicester.

Richard Samuel Attenborough was born on 29 August 1923.

He and his brothers David, the television naturalist, and John were brought up by fervently do-gooding parents - their father was principal of University College, Leicester.

Both father and mother were Labour Party activists whose commitment extended to adopting two Jewish refugee girls from Germany when World War II broke out.

Attenborough inherited a belief in the importance of community and society. Apart from a brief flirtation with the Social Democrats he was a lifelong member of the Labour Party, and much of his work reflected his political beliefs.

As the murderer John Christie in 10 Rillington Place

He made his film debut while still a drama student in 1942, playing a cameo role as a cowardly young stoker on a naval destroyer in Noel Coward's In Which We Serve.

Over the next 30 years - interrupted by three years' service in the RAF - he became a star and one of Britain's most reliable character actors.

Christmas fixture

His most astonishing performance was his chilling portrayal, in 1947, of the teenage hoodlum and murderer Pinky in Brighton Rock.

On stage he was part of the original cast of Agatha Christie's long-running whodunnit, The Mousetrap.

He later became a fixture of a score of British television Christmases as Bartlett in 1963 prison camp drama The Great Escape.

In 1964 he won a best actor Bafta for his portrayal of the downtrodden husband of a deranged spiritualist in Seance on a Wet Afternoon.

The award also recognised his performance as a martinet sergeant major facing a native uprising in Guns at Batasi.

Parkinson to Attenborough in 2000: "You were the pin-up boy of 1950s movies"

His greatest skill as an actor was the sympathetic embodiment of ordinary though never mundane men in extraordinary circumstances.

It served him especially well in 1971 when he played the mass murderer John Christie - outwardly normal, in reality a psychopath - in 10 Rillington Place.

He was knighted for his efforts in 1976. But he had become frustrated with acting, in which he only ever interpreted other people's work.

He began producing films, then making them. "Becoming a director enabled me to do things I couldn't do as an actor," he said.

He was a film-maker with a mission, believing popular cinema had a capacity to make the world a better place.

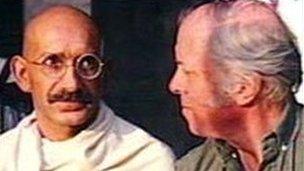

His greatest achievement was his 1982 epic Gandhi, starring Ben Kingsley as the outsider hero whose moral courage and sense of purpose enabled him to change the world.

Political statements

Gandhi won eight Oscars, including best actor and best director. But it took Attenborough 20 years to raise the money to make it.

He mortgaged his house, sold possessions and took roles in films he described as "terrible crap" to help pay for what became an obsession.

Along the way he directed other films. There was a version of Joan Littlewood's anti-war satire Oh! What a Lovely War. There was Young Winston, about Churchill's early years, and the war epic A Bridge Too Far.

After Gandhi came his adaptation of the musical A Chorus Line. It was followed by Cry Freedom, the story of the murdered South African black activist Steve Biko and Donald Woods, the white journalist who took up his cause.

Like Gandhi, Cry Freedom was a box office and critical success. Like Gandhi, it was anti-racist, anti-imperialist and impeccably liberal, as well as a strong, eminently watchable drama.

Both films wore their political hearts on their sleeves. And both were occasionally criticised for being overblown, overlong, sentimental and even patronising.

Some of his films were flops. His 1992 biopic of Charlie Chaplin failed to make money, while Grey Owl, about a pioneering Canadian Indian environmentalist who turned out to have been born in Hastings, went straight to video in the US.

His final film, 2007's Closing the Ring, was judged to be a muted finale to a distinguished directorial career.

But Shadowlands, released 14 years earlier with Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger, was a commercial and critical success.

Committees full of 'darlings'

The story of children's writer C S Lewis and his late love affair with American poet Joy Gresham was an unashamed and astonishingly effective tear-jerker.

It befitted a film by a man who was himself famous, even notorious, for weeping in public.

Late in life Attenborough resumed his own acting career in Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park in 1993, the year he became a life peer.

He also starred as Santa Claus in Miracle on 34th Street and had a cameo role in 1998's Elizabeth.

As well as being one of Britain's foremost actors and directors, Lord Attenborough was also one of its most active public figures.

His vast entry in Who's Who listed more than 30 organisations of which he was or had been a director, trustee, fellow, chairman or president.

Gandhi was 20 years in the planning

They included the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, the British Film Institute, Capital Radio, Channel 4, the Tate Gallery, the Muscular Dystrophy Group and Chelsea Football Club.

He put down his habit of addressing everyone as "darling" to serving on so many committees with so many famous people he was never able to remember their names.

At a Downing Street seminar in the early 1980s on the parlous state of the British film industry, the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher expressed deep concern.

"Why wasn't I told?" she asked. "Darling, you never asked," Attenborough is said to have replied.

His personal life was apparently irreproachable. His marriage to the actress Sheila Sim was one of the longest-running in showbusiness.

They wed in 1945 and had three children, including the theatre director Michael Attenborough.

Tragedy struck the family in 2004 when the Asian tsunami killed his 14-year-old granddaughter Lucy Holland, as well as his daughter and her mother-in-law, both called Jane.

Charming but determined

Lord Attenborough broke down in tears as he paid tribute to them at a service in London's Southwark Cathedral the following year.

He went on to channel his energies into supporting the Khao Lak Appeal, in aid of a Thai village struck by the tsunami. The appeal raised more than £1 million.

Lord Attenborough had great charm and immense energy and knew how to use both. The public saw a gregarious theatrical extrovert, but beneath the gush there was a determined and decisive man.

Throughout an extraordinarily busy life he remained passionately committed to his chosen craft of film-making.

And he always believed films should be more than merely entertainment - while never forgetting that before they could do anything else, they had to entertain.

- Published25 August 2014