Remembering Philip Larkin 25 years on

- Published

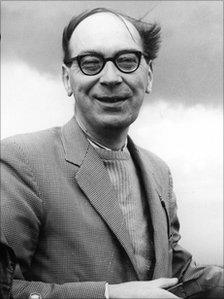

Philip Larkin became a giant of poetry after The Less Deceived was published

To some, Philip Larkin was Britain's greatest 20th Century poet. To others, he was a reclusive, woman-hating, self-absorbed bigot.

To Jean Hartley, who published the poetry collection that propelled him to literary greatness, he was a generous and funny friend.

On the 25th anniversary of his death, Mrs Hartley remembers the Larkin she knew.

After Philip Larkin first paid a visit to Jean and George Hartley's humble house in Hull, from which they produced the influential poetry magazine Listen, he remarked to a friend that it was "frightful".

A bare two-up, two-down workman's cottage with an outside lavatory and indoor slugs, it was, Mrs Hartley now admits, "a hovel".

"I doubt if he'd ever been in a little working class house like ours before," she says.

"He must have wondered whether we could possibly make a good job of the book."

Larkin was of solid middle-class stock, brought up in a respectable detached home, and had moved to Hull to run the university library. The husband and wife could not afford a table to eat on.

The poet was initially drawn to them out of convenience. Established publishers had rejected him, but the Hartleys were enthusiastic about his work.

The different backgrounds proved awkward at first, especially given that Larkin's father, Coventry's Nazi-admiring city treasurer, passed on some (but not all) of his right-wing instincts.

Mrs Hartley recalls an early stand-up row about politics.

"I remember shouting at him: 'My mother was a servant and I'll have to vote Labour because they're the people who have got my interests at heart.'

"And then I suddenly realised that neither of us were really interested in politics. We were both giving our gut reactions that we'd inherited from our different class backgrounds."

The pair found common ground in poetry. Unsolicited, Larkin had submitted three poems to Listen with no knowledge of its owners or origins.

"They were completely different from anything we'd seen before," Mrs Hartley explains. "They had the speaking voice there that was immediately understandable.

"They did have levels and depths, but they were perfectly accessible on one reading and that was so refreshing."

The couple were so impressed that they invited Larkin to release the first book from their home-spun publishing house, The Marvell Press.

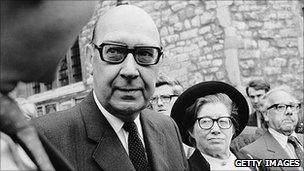

Larkin died on 2 December 1985 at the age of 63

Titled The Less Deceived, the poetry collection emerged in 1955 and gradually became a literary sensation, establishing Larkin as one of the UK's finest writers.

And the visits to the Hartleys' home continued.

"We all had a lot in common, not least on the literary front," Mrs Hartley says.

"If the weather was good we'd go out for a walk. Otherwise we just talked. And he was so funny. He was the funniest man I've ever met.

"Even when he was enveloped in gloom over some illness or mishap, he managed to make it sound absolutely hilarious."

Mrs Hartley has published her own account of her friendship with Larkin, which has been turned into a stage show.

The poet could also be loyal and generous, she recalls.

"He helped me out financially when I left George and was a single parent and a student," she says. "He opened a book account for me.

Jean Hartley's story has been turned into a book and a stage show. Photo: Larkin25/Dennis Low

"If he was with you, then he was interested in you. He wasn't telling you about his triumphs and his successes. In fact he never mentioned them.

"He was talking about what you wanted to talk about and your concerns."

After Larkin died in 1985, the publication of his letters, followed by a biography by his friend and fellow poet Andrew Motion, gave the world a candid and often unflattering insight into his inner life.

They laid bare his "hostility to women" (as Motion put it), his often lewd sexual thoughts, the unreconstructed right-wing views and his ugly prejudices.

"It was shown recently that one child in eight born now is of immigrant parents," he wrote to his mother in 1970. "Cheerful outlook, isn't it? Another 50 years and it'll be like living in bloody India."

'Foul-mouthed bigot'

As a result, the national treasure was irrevocably tarnished.

Peter Ackroyd described him as a "foul-mouthed bigot", while AN Wilson dismissed him as "a kind of petty bourgeois fascist" and a "nutcase".

A quarter of a century after his death, his supporters have been attempting to rehabilitate his public image.

A statue was unveiled in Hull on Thursday, the climax of a five-month festival organised by the Philip Larkin Society, of which Jean Hartley is a founding member.

His views should be put into historical context, she believes.

"It's partly a matter of when he was born - 1922," she says. "You think of the kinds of class attitudes, race attitudes, sex attitudes that he would have inherited.

"There are traces of all of those but they never had any sort of influence over the way he behaved with people, whoever they were, whatever their colour."