Is live music under threat in the UK?

- Published

Sir Paul McCartney played the 100 Club when it was under threat of closure

While London's 02 arena has been named the most popular music venue in the world for the fourth consecutive year, fringe venues up and down the country are being threatened with closure.

The 100 Club on London's Oxford Street has only just been saved, after a high-profile campaign supported by Sir Paul McCartney and Ronnie Wood. But the Luminaire, north of the city, is no more.

In 2009 Leicester's iconic club The Charlotte, which saw early gigs from Oasis and Coldplay, shut its doors.

Manchester has lost Jilly's Rockworld and the Music Box, although other venues have readily taken their place.

So how are other cities faring?

BBC 6 Music took a tour of the UK, speaking to bands, promoters and fans in five different locations to take the pulse of the live music scene.

Glasgow

Venues like Barrowlands and King Tut's are internationally renowned

In the words of Glaswegian band Simple Minds, the city's music scene is alive and kicking. Promoters say it offers a diverse mix of venues, while fans reckon live music is booming.

Stuart Braithwaite, from experimental rock band Mogwai, even says the city exerts a gravitational pull on talent.

"So many artists see Glasgow as a place to listen to and make music that they move there. So a lot of the really good bands are young people that are not even Scottish."

Live events organiser David Weaver agrees that the scene is thriving.

"The amazing thing is just how much people help each other out," he says. "There are so many new bands of all sorts of genres, but the venues are busy for bands that might be playing their first gig.

"Even a place like King Tut's, which has a worldwide reputation, really supports new music. They recently put on two weeks of new bands called the 'New Year Revolution', and it was packed out every night."

Malky B, a music blogger and concert promoter, says Glasgow's size is the key to its success.

"Whereas in most cities the venues are quite spread out, in Glasgow the city and the music are partners together. That brings a unique style to the music that gets produced here," he says.

"There has been a downturn economically, but so far bands and venues have managed to weather that."

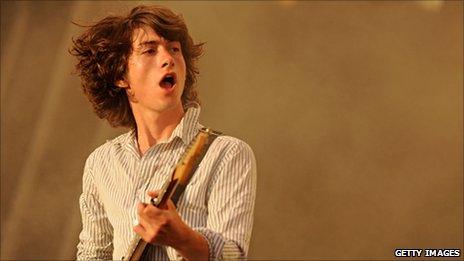

Sheffield

Arctic Monkeys are Sheffield's biggest success story of recent years

"Musically, I don't think it's as healthy as previous times," says John McClure, frontman of indie pop band Reverend and the Makers.

"Around the time of the Arctic Monkeys, Sheffield became trendy for five minutes. Reverend and the Makers and Richard Hawley did well. It's left a bit of a hangover."

Promoter Rupert Dell runs The Leadmill, a legendary club based in a former flour mill that was pivotal to the rise of local bands ABC, Heaven 17 and the Human League. He agrees the scene is in limbo.

"It's very difficult to get customers to pay to come and see newer bands. Five years ago we used to be able to do that, no problem."

The Leadmill has managed to stay open, but others have not been so lucky. Over the last year The Boardwalk, The Shakespeare and The Stock Room have all gone dark.

"The Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Arctic Monkeys - they all played at the Boardwalk," says McClure. "I think it's very sad that it's going to become a Poundland."

But while treasured venues are struggling, some entrepreneurial music fans are staging free shows.

Among them is James O'Hara, who says these concerts are the only way forward.

"It's all in line with the fact that music itself is struggling as a product. With free gigs, the negative is that you can't make as much money from being in a band. But the positive is that more people will come and see you."

Emerging indie band Seize the Chair don't take any money on the door. But they still manage to make ends meet by selling merchandise and taking a share of the bar receipts.

"Sheffield's a really easy place to get gigs," they say. "There's lots of promoters, and everyone's willing to give you a hand."

"What kids want to do is spend no money, listen to amazing music and go somewhere a little bit alternative," adds McClure.

"The party scene is starting to provide that and I think that's where the next wave of good Sheffield music is going to come from."

Belfast

Northern Irish bands like Snow Patrol have charted internationally

There was panic in Belfast last summer when pub owners CDC Leisure went into administration. Amongst the chain's portfolio was The Limelight, probably Northern Ireland's most iconic music venue.

It was the place where Oasis played the day that Definitely Maybe went to number one, and has also hosted gigs by Blur, The Strokes, Paul Weller and local bands Ash and Snow Patrol.

But the club has survived, thanks to Belfast's all-for-one music scene.

"Belfast is the only place I know where the sound engineer will do as much to promote the night as the band themselves," says BBC Introducing presenter Rory McConnell.

Davy Matchett, from Third Bar artist management, agrees: "If you're in a band, and you need a guitar pedal, there's someone you can phone and they'll give you their guitar, or their pedal, or whatever."

He says Belfast City Council has also recognised the investment potential of local bands succeeding internationally.

"They've been very active in helping both industry people and bands go to things like the South By Southwest festival, to represent Northern Ireland."

Dave Nealy, who runs The Limelight, says Belfast bands also have a unique opportunity to meet their heroes without leaving home.

"We are slightly removed from the rest of the UK, so we have more chance of putting on a local act with a big headliner, because there's a bigger chance that they won't bring a support with them."

Even without the pub and club scene, there are plenty of informal venues around.

"A lot of bands in Belfast start playing in church halls," says Sam Halliday from Top 40 indie band Two Door Cinema Club. "It means a lot of kids can go to see their favourite bands without parental supervision."

The only cloud on the horizon comes in the form of the spending review. Rosa Solanis from Arts Council Northern Ireland says she is "looking at a 23% cut" in the forthcoming budget.

"The impact on music is going to be very negative, especially as our role is in fostering emerging talent, helping artists before they become commercially viable.

"Audiences will lose out too, because the number of gigs will diminish. So we've been campaigning for a fair deal for the arts."

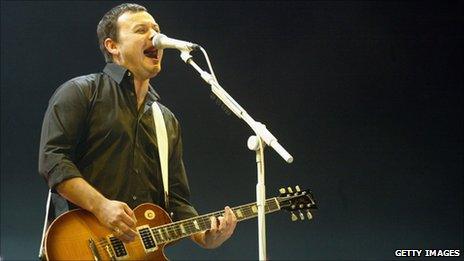

Cardiff

Local heroes Manic Street Preachers can sell out the Millennium Stadium

Cardiff boasts the 60,000 capacity Millennium Stadium, which has played host to the likes of Madonna and Sir Paul McCartney. But smaller venues have been less fortunate.

The Point, a venue which hosted gigs by Super Furry Animals and The Bluetones, was forced to close in 2009. Clubs like Ten Feet Tall say they can't book bands who use drums before 2300 because of noise regulations.

Manic Street Preachers frontman James Dean Bradfield mourns the loss of several big clubs in the city.

"When I was a kid I used to go to venues like the New Ocean Club which is no longer there, The Square Club which is no longer there, and a place called Nero's which is no longer there.

"That's three venues off the top of my head, where I saw bands like Waterboys, Spear Of Destiny and Siouxsie and the Banshees - all of which are gone."

Isaac Jones runs a local record label and plays guitar with Among Brothers. He agrees the situation is far from perfect.

"In the back of your mind, there's always a worry that you're going to lose money. What we've found, both with gigs and the record label, is that you need to collaborate to reduce the risk.

"Get a friend's band and ask them to go in on it with you. The more people that are involved, the more people will put effort into promoting it."

Despite his concerns about the commercial side of the business, Jones says that, creatively, bands are thriving.

"It feels as though there is a new band coming out each day. It's good when they start mixing and mingling with other bands, and that's when you get the good shows."

As in Sheffield, new ways of promoting music are springing up to take the place of traditional venues.

"There's more people open to doing small shows," says John Rostron, who runs the SWN Festival. "But, interestingly, it's in spaces that it didn't exist in before."

"It is much easier for small bands to get those first gigs and step ups."

Brighton

Brighton's scene is moving away from DJ sets to live bands

Brighton is home to a host of musicians, from Bat For Lashes to Fatboy Slim and The Maccabees. But soundclash dance act The Go! Team say the city's live music scene is "struggling".

"Recently one of the mainstay little venues, the Freebut, closed down because it encountered problems with noise restrictions," says band leader Ian Parton.

"There was a weird spate of closures at that time. The Engine Room was another one."

Parton identifies two problems - a surplus of venues, and Brighton's proximity to the capital.

"Brighton is turning into London-by-Sea, and these little venues are not getting enough money in," he says.

Local promoter Trevor Madison says there are simply too many music nights in the city. "Everyone's trying to get in on the live scene. Promoters have realised that's where the action is at the moment.

"The clever bands are the ones that realise they need to make it work for them, rather than running out and playing every event going," adds Simon Parker, who runs long-standing local band showcase Cable Club.

"After a couple of months, some bands find they've totally exhausted their fanbase."

In contrast to many other cities, Brighton's public officials realise the value of live music. They licence as many as 60 music events and festivals every year, including The Great Escape.

"We are very blessed in the city as there is so much going on," says Donna Close, Arts and Cultural Projects Manager at Brighton and Hove City Council. "Our role is very much about supporting that.

"For example, The Great Escape Festival, when it was first looking for different cities, came to Brighton and we encouraged the organisers to choose us by telling them how great the music scene was here."

The city even attracts foreign talent - such as platinum-selling Australian artist Sarah Blasko, who calls Brighton home when she is in Europe.

"It's a good place to base yourself while you're writing and doing something creative," she says.

"It's not just a strong music scene, there's a proper artistic community. Lots of visual artists and musicians. It always feels like there's something going on."

Reports compiled by BBC 6 Music and BBC Introducing teams across the UK.

- Published1 September 2010

- Published17 December 2010