Obituary: Cliff Michelmore

- Published

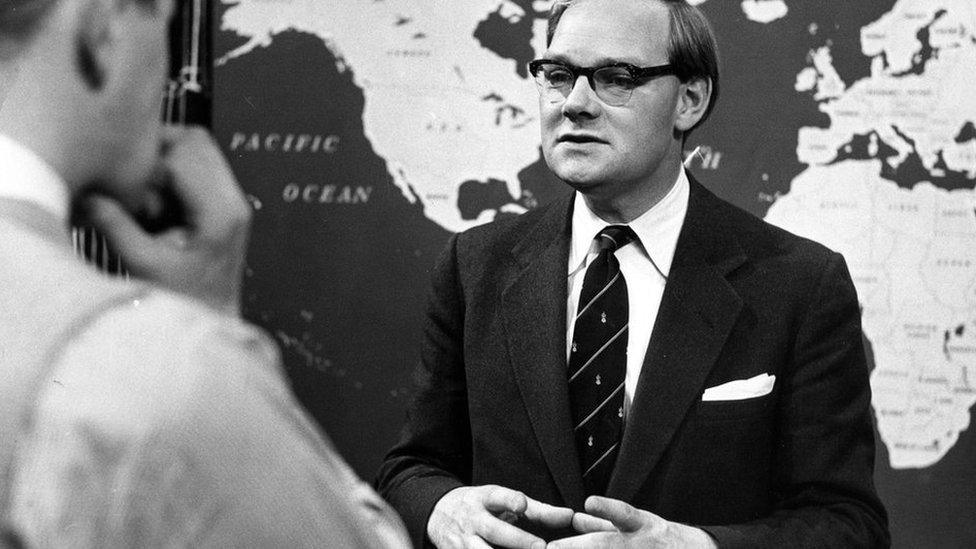

The consummate professional

With his avuncular manner and trademark spectacles, Cliff Michelmore was one of the best-known presenters on British television.

His calm and unflappable style became his hallmark, particularly during the decade when he fronted the BBC TV current affairs programme, Tonight.

He was a natural choice to handle big, set-piece events such as the BBC's coverage of a general election.

And he presided over moments of live drama, notably the assassination of President Kennedy and the return of the damaged Apollo 13.

Arthur Clifford Michelmore was born on 11 December 1919 in Cowes on the Isle of Wight.

He never really lost touch with his birthplace, always proudly describing himself as an island person.

He was the youngest of six children and, following the death of his father when he was just three, he was brought up on a local farm by his older sister and her husband

Faux accent

He rejected the opportunity to become a farmer, something he later said he regretted.

I'm a bit of a workaholic," he said. "And you have to be something of a workaholic to work on a farm."

Instead he joined the RAF and was commissioned during World War Two before joining the British Forces Network in 1947 as Deputy Director.

He'd written scripts previously for the BFN but his arrival to run the RAF element of the station sparked a real interest in broadcasting.

He took on a variety of on-air roles including adopting a faux West Country accent to present a weekly gardening feature.

He also took part in radio dramas, once playing Little John to Nigel Davenport's Robin Hood in a play that also featured Brian Forbes and Roger Moore.

Love blossomed behind the Family Favourites microphone

Michelmore achieved his big break when he was asked to fill in at the Hamburg end of Two-Way Family Favourites.

The programme went out on Sunday lunchtime on BBC radio and linked members of British forces serving round the world with their families at home

It was fortunate both for his public and his personal life. After striking up a warm on-air relationship with the London anchor, Jean Metcalfe, he eventually married her.

Technical issues

After working as a freelance reporter for the BBC in the South West of England he moved into children's television, presenting the fortnightly Saturday programme Telescope, and also did sports commentary.

In 1955 he moved into current affairs, presenting the BBC TV programme Highlight.

The programme quickly gained a reputation for its uncompromising interview style, something of a departure from the much more restrained way such things were usually done at the time.

In 1957, the BBC launched a new early evening current affairs programme and Michelmore moved over to present it.

The Tonight programme broke new ground

The programme blended serious issues with more quirky human features, and also made the names of reporters such as Alan Whicker, Derek Hart, Fyfe Robertson and Magnus Magnusson.

Tonight broke new ground in television news programmes. Studio equipment appeared in shot and Michelmore often presented items while perched on the edge of his desk.

It was a far cry from the formality that was the trademark of news presentation in the 1950s, and Tonight regularly attracted audiences of more than eight million.

His laidback style meant he effortlessly dealt with the technical problems that were part and parcel of a live news programme at the time.

On one memorable occasion he introduced a news item only for nothing to appear on the screen. Michelmore was unfazed.

"Well, we were supposed to be showing you a piece of film now, but it's not there," he said. I don't know what's going on. And it seems no-one else does either."

Aberfan

He later admitted that, beneath the calm exterior, his stomach was churning over during these moments of technical drama.

Tonight was voted best factual programme by the Guild of Television Producers and Directors Television Awards (now the Baftas) in both 1957 and 1958.

He was live on air when the news came through of the assassination of President John F Kennedy on 22 November 1963.

With confusion in the gallery as to what had happened he was asked to fill. "It was certainly a moment that I will remember for ever."

After Tonight ended in 1965, he went on to present its successor programme, 24 Hours.

He was on air when Kennedy was assassinated

His most poignant moment came when he was sent to cover the 1966 disaster at the Welsh village of Aberfan, where a slagheap had collapsed on to a junior school, killing 116 children and 28 adults.

With rescuers still frantically digging through the rubble behind him, Michelmore struggled to keep his composure as he began his report to camera.

"I don't know how to begin," he said "Never in my life have I seen anything like this. I hope I shall never see anything like it again."

Holiday

In 1967, he was chosen to front the UK segment of Our World, an ambitious live programme that used the newly emerging satellite broadcast technology to link television broadcasts from around the world.

The BBC contribution featured the Beatles in a live performance of All You Need Is Love.

Michelmore also fronted the BBC's coverage of the Apollo space missions, including the first Moon landing in 1969 and the heart-stopping return of the damaged Apollo 13 in April 1970.

In 1969, he quizzed Prince Charles in the heir to the throne's first TV interview.

The unflappable presenter of election results

And he was a natural choice to be the calm front of BBC general election results programmes.

He also appeared on the 1971 Morecambe and Wise Christmas Show, taking part with other presenters in a top hat and tails dance routine.

He went on to present the Holiday programme, in which reporters visited various holiday destinations and compiled pieces on the attractions they found there.

There was some criticism at the time that many of the destinations featured were out of the price range of the majority of the programme's viewers.

The unflappable presenter was still broadcasting on radio in his 80s.

With John Carter and Norma Shepherd on Holiday

He also fronted a 2007 BBC Parliament programme looking back on the 1967 devaluation of the pound, a story he had covered at the time.

Despite his long service with the BBC he never had a contract and remained a freelance throughout his career with the Corporation.

"Every day since I joined in 1950," he later said. "I've felt insecure. If you are a freelance someone can come up at any time and take your living away; just like that."

The writer and broadcaster Antony Jay, who was one of the editors of Tonight, paid this tribute on Michelmore's 90th birthday:

"There was no pretence, no feeling of 'performance' about him, in spite of the consummate professional and technical skill he brought to the programme. He was just Cliff, take him or leave him. And of course the audience took him, in their millions."

Many of those millions will recall Michelmore's famous sign-off: "The next Tonight will be tomorrow night - goodnight."