'REM were a band that had no goals,' says Michael Stipe

- Published

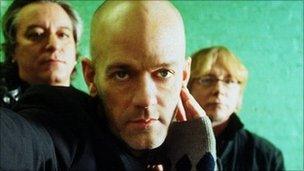

REM released their 15th album, Collapse Into Now, in March

REM's 30-year career began in the underground, with the groundbreaking and influential mid-80s albums Murmur and Reckoning.

They finally achieved mainstream success with 1988's alternative rock masterpiece Green, and progressed to MTV-fuelled international success with singles like Losing My Religion and Everybody Hurts.

Somehow, they managed to enjoy world-wide mainstream recognition while also maintaining their status as one of the most esoteric, unique voices in rock music.

In doing so, they opened the door for alternative rock bands like Nirvana and Pearl Jam, and set a template (both musically and ethically) that's been followed by everyone from Radiohead to Arcade Fire.

In the wake of the release of the band's 15th album, Collapse Into Now, Michael Stipe granted a handful of interviews. Speaking to BBC 6 Music's The First Time, he displayed little of his trademark intensity and solemnity.

"His reputation for fixing you in his eye and carefully considering every aspect of every question is well justified," says presenter Matt Everitt. "But Stipe seemed happy to chat about his early obsessions and his comical ignorance of musical history."

When did you first become aware of music?

It would have been the Beatles, Michelle, my belle. I was staying with a German friend and she was making cabbage soup for me. That song came on the radio, and I remember standing alone in the living room, looking at that radio on a tall shelf and thinking that it was really beautiful.

Did you have a musical upbringing?

Not particularly. My parents were very specific about what they loved, and they would play it over and over again. Although I come from an artistic family, music was not a huge part of my upbringing.

What was the first single that you owned?

My grandmother took my two sisters and I to a record store, Mr Pemberton's Record Store in Texas. He had some singles that were discounted, so we were able to buy whatever we wanted.

We bought an Elvis Presley album, for one of his films called Double Trouble, and a Disney Film called The Parent Trap starring Hayley Mills. Amongst the singles was Tammy Wynette's D.I.V.O.R.C.E. and I Want To Hold Your Hand by The Beatles.

Now, if that isn't random, I don't know what is.

It's definitely an eclectic mix.

As a pre-teen, before punk rock radically changed my life, there were songs on the radio that resonated with me and, to this day, I don't know why.

Such as?

The band were a four-piece until drummer Bill Berry quit in 1997 after suffering a brain aneurism two years before

Benny And The Jets by Elton John. It seemed like it came from another galaxy. As an adult who makes music, I realise now that the production on that song is probably the weirdest to ever make the top 20.

Your first single was Radio Free Europe. What do you remember of recording it? Were you excited?

No, I wasn't! I didn't know the process of recording. In fact, it wasn't until our second album, Reckoning, that I realised the difference between the bass guitar and the guitar. I didn't know which one did which sound. I knew the bass guitar had four strings on it… because I could count them. But I didn't know the bass guitar did the low notes. That's how ignorant I was of music.

What was the first REM song that you felt connected with a mainstream audience?

From the first show we did I felt like a pop star, because people clapped when I did something. On some level, that's all part of the insane insecurity and courage it takes to perform in the first place.

But I think that when The One I Love came out and went into the top 20 in the US, that's when it felt like, "Wow, this is really serious. This is real."

It's always gratifying when someone works for a long time - and this doesn't just have to be in music - and finally achieves their goal. How did that feel?

But we didn't know what we wanted. We were the band that had no goals. The fact that we were making records and touring felt like this amazing adventure to us. We didn't necessarily want to conquer the world - but then we ended up doing exactly that in some small corner of the universe that belonged to pop music and us.

You've made a film for each of the songs on the new album. How did that come about?

Stipe has branched out into film, both as an actor and producer

To an 11-year-old child, the album is a thing of the past. But I think an album is something quite significant. A medium and a format that needs to be celebrated. So how do we do that in 2011? One thing we can do is create something that's going to be presented on YouTube, or you can watch on your phone. That's what these 12 films were all about.

When you were recording Collapse Into Now were you aware of trying to celebrate the album format. Did you sequence it to be listened to as a complete body of work?

Sequencing is absolutely important to an album. It's perhaps one of the most important things. Also being able to edit yourself: If you've written 17 songs, being able to bring it down to a number that will create a complete piece. That's a skill I don't own, but Peter [Buck] does.

REM is credited with being a band that took the alternative into the mainstream. Do you look at bands like Nirvana or Pearl Jam and see some of yourself?

Never! I just don't see it. It's like when people compared REM to The Byrds. I didn't get that either. It was the way Peter picked the guitar instead of strumming it, but I didn't know about the history of music to know that.

So when that's turned around on me… I only recently found out that people think my voice is unique. People say they can recognise it instantly and I never knew that. It's not false modesty or humility. I honestly had no idea.

Does it feel like every REM album might be the last one?

I put so much into the work we do that, when I'm done, I feel like I'd never be able to do it again. For better or worse, one of the things I'm most proud of is that we've never taken the advice of other people over our own. So the triumphs that are ours are distinctly and completely ours. And the failures are also completely ours. So looking back, I get equal dollops of humility and triumphant joy.

You can hear the full interview with Michael Stipe on BBC 6 Music on 17 April at 1200 GMT. Collapse Into Now is out now.