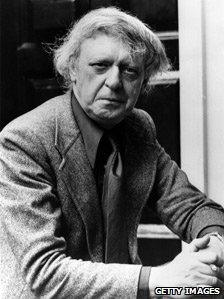

Anthony Burgess archive yields lost gems

- Published

Burgess' script for a TV mini-series about Atilla the Hun was never filmed

Previously unknown stories, scripts, letters and musical compositions by the late author Anthony Burgess have been found in an archive of his possessions.

The contents of three of his houses were left to the International Anthony Burgess Foundation in Manchester by his widow, who died in 2007.

Most famous for writing A Clockwork Orange, Burgess wrote 33 novels in all.

Researchers have now uncovered some 20 unpublished short stories as well as unproduced film and theatre scripts.

They include a previously unknown movie script about Napoleon Bonaparte, which was to have been filmed by director Stanley Kubrick.

The pair had worked together when Kubrick filmed Burgess' 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange, which depicted the ruthless sexual "ultra-violence" of a teenage gang leader in a lawless society.

The film caused an international outcry when it was released in 1971, leading Kubrick to withdraw it from cinemas. But it is to be recognised as a classic with a special screening at the Cannes Film Festival next week.

Burgess' original screenplay for the film is among the most prized artefacts at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation.

The typescript, which has never been published, was rejected by Kubrick, who opted to write his own instead.

Burgess' version is interesting because it is "very different from the novel", according to Dr Andrew Biswell, the author's biographer and the foundation's director.

"It's actually quite a bit more violent than the novel. There's a scene early on where Alex opens his bedroom cupboard and it's full of drugs, hypodermic needles and a child's skull."

The archive includes Burgess' original screenplay for A Clockwork Orange

The foundation is now hoping to publish Burgess' version.

The archive also includes parts of a script Burgess wrote for a stage show about the escapologist Harry Houdini, which he was working on with Orson Welles.

Among the literary works are a copy of a full-length, unpublished history of London, which blends fiction with non-fiction, plus Burgess' tome on the history of English literature, which never had a mainstream release.

Some of the unpublished short stories, meanwhile, have only survived as recordings on audio tape.

Burgess often recorded himself reading his work aloud to see how they "fell on the ear", according to Dr Biswell.

"Burgess was known as someone who wrote really long novels, so it's a big surprise to find him working in this shorter form," he says.

"A lot of the stories are very nasty and tending towards the supernatural as well - a lot of ghost stories or stories about Gods who come down to earth."

Another part of the collection is given over to around 200 musical compositions, the vast majority of which have never been performed or recorded.

They include three symphonies and other orchestral works of varying lengths plus musical adaptations of poetry and the score for a ballet about Shakespeare.

Other abandoned dramatic projects demonstrate a fascination with great figures from history.

He started work on scripts for TV mini-series about Atilla the Hun, Sigmund Freud and Michelangelo, but none went into production.

He wrote a musical about Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, which has never been performed, and a musical adaptation of James Joyce's novel Ulysses.

"The amount of material which people don't know about I think heavily outweighs the known," Dr Biswell says.

"Even though Burgess was productive - he published a lot - a good deal of what we've got here has always been below the waterline. It's never been made available in a public way until now."

Burgess was born in Manchester and lived in the city until the age of 23.

He died in 1993 and the foundation was set up to look after his estate by his second wife Liana before her death. The writer has no surviving immediate family members.

Based in a former mill, the foundation has taken possession of items from the couple's homes in London, Monaco and Italy.

They include 50,000 of Burgess' books and 20,000 photographs. It is also home to files and letters donated by his agents in London and New York.

There are also some unusual items, such as a signed photo from his friend and comedian Benny Hill, a set of home-made tarot cards and translations of obscene Roman poems that he worked on for Playboy magazine.

Dr Biswell said the collection demonstrated the extent of Burgess' "encyclopaedic imagination".

The author embraced cultures, speaking six languages as well as English, and tackled an "epic range" of subjects, Dr Biswell explained.

"I'm staggered by the extent of the collection sometimes - I come down into the basement and I look at it and I think, my God, did this man never sleep?"

The foundation is now planning to publish some of the most significant written works that it has found, and to stage performances of his musical compositions.

It is also supporting young artists who are working with similar themes to Burgess, and is considering commissioning people to complete the unfinished literary, dramatic and musical works.

Dr Biswell also asked for people who knew Burgess, or have material relating to his life and work, to get in touch.